Grief, Memory, Three O'Clock in the Morning

Pockets

As she stopped to close her umbrella, the wind carried to her feet a piece of mistletoe and, glancing up, she saw that cheap tinsel icicles and bunches of mistletoe had been tied on the street lamps of the square. It looked pretty, and rather poor, and she thought of the giant tree in Rockefeller Center. She suddenly felt sorry for Paris … Her throat went warm, like the prelude to a rush of tears. Stooping, she picked up the sprig of mistletoe and put it in her pocket. Mavis Gallant, The Other Paris.

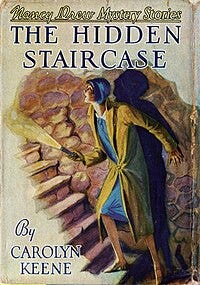

I have a little side project — I may have mentioned this before — that involves keeping track of pockets as they occur in literature and journalism; pockets, and the things we carry in them. For instance, towards the end of The Hidden Staircase, by the indefatigable and also fictional Carolyn Keene, Nancy Drew bravely leads a posse of badge-wearing lawmen through a secret passageway to an old iron door behind which, she inuits, languishes her kidnapped father, lawyer Carson Drew. One of the chaperoning officers, Captain Rossland, extracts from his pocket “a penknife with various tool attachments,” and quickly picks the lock. The door swings open, and lo! Nancy was correct in her estimation, for there, alive but evidently drugged, is her cherished papa! Captain Rossland, who has seen this kind of thing before, says, “‘I’d say Nathan Comber [hiss! boo!] has been giving your father just enough food to keep him alive and mixing sleeping powders with it.’ From his trousers pocket the officer brought out a small vial of restorative and held to to Mr. Drew’s nose. In a few moments the lawyer shook his head, and few seconds later, opened his eyes.”

Good old Captain Rossland! So dependable! One can imagine him of a morning, getting ready to leave his home (it would have been tidy and well-secured) for work and patting his pockets to make sure they’re supplied with a revolver, a few spare bullets, a Swiss army knife, and a small vial of restorative. Be prepared!

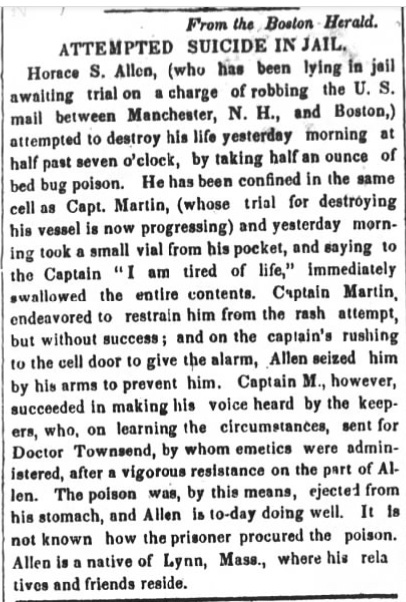

Having found such a reference in Literature — and I will throw down the gauntlet before anyone who dares suggest Nancy Drew doesn’t qualify as same — I then check news sources to see how — taking this present instance as an example — vials in pockets might play out in the historical record. Hence, this clipping (May 4, 1850) from the Tri-Weekly Journal, published in Wilmington, North Carolina. The original paper of record, as you’ll note, was the Boston Herald.

I organize my master list of these cullings alphabetically — I think of it as a pocket dictionary — and this one, which could live with the V’s for “vial,” or the P’s for “prison,” or the A’s for “arsonists (adjacent),” I’ll file under B for bedbug. (For me, it calls to mind one of the entries I’ve slotted under C that tells the story of a trapper who accidentally discharged his pistol when it was pointed in his direction but the bullet was deflected by a container he’d stored in his pocket in which he carried his liquid coyote bait. He must have walked home very quickly if he was passing through coyote territory.)

I also gave time and thought to selling my clothes. I sold them to the gypsies in the flea market. Once I got a dollar-fifty for a coat and a skirt, but it was stolen from my pocket when I stopped to buy a newspaper. I thought I had jostled the thief, and when I said “Sorry” he nodded his head and walked quickly away. He was a man of about thirty. I can still see his turned-up collar and the back of his head. When I put my hand in my pocket to pay for the paper, the money was gone. Mavis Gallant, When We Were Nearly Young.

Whatever will I do with all these pocket references? I’ve thought they would settle into a book of the bathroom-browsing variety — I’m quite sure they would — but the imbalance in the blood, sweat, and probably tears it would require to publish such a thing — it would have to be self-published, no commercial firm would take it on — and the return on whatever the investment would be so skewed that it would need to be a labour of more love for the project than I currently possess, or ever am likely to. It amuses me. It kills the time I might otherwise devote to day drinking or surfing Pornhub. So, I guess it’s wholesome.

I feel similarly about this digging into the origin story (as now, apparently, we say) of Mavis Gallant (MG). For me, it’s a diversion and also a challenge. At this stage of the game I’ve read pretty much every published interview with her, and pretty much everything that’s been published, critically and biographically. What I’ve been unearthing and reporting here— again I thank the wonderful Linda Granfield for her many leads and suggestions — is — to me, at least — new. That’s not to say that it hasn’t been known and disseminated and that I’ve simply overlooked its disclosure. Nothing could be more likely; I’m careless by nature, and the rankest of amateurs when it comes to this stuff, so I lay no claim to having produced anything original or definitive in the big bad world of MG scholarship.

What I do own, however, in this regard, are qualms that verge on the existential, or something like it. I mean that I often ask myself how or whether any of what I’m doing matters. Does anything come from what I’ve been finding and writing that adds an actual gloss to an understanding of MG’s writing which, when all is said and done, is what matters, the sine qua non. I could make the case that yes, here and there, at least, it does. Knowing, for instance, that her uncle Nicholas, whose story has preoccupied me recently, was an enthusiastic polygamist, adds a kind of shading to the story “Rose,” which alludes to a bigamist uncle, and is also a small demonstration — should one want one — of how MG would deploy, but mask, her own story in her fiction. The uncle in “Rose” is named as her father’s brother, but Nicholas was a Wiseman, brother to her mother, Benedictine. And I do find it fascinating to know that Nicholas spawned two children (that I know of) by the first two (again, that I know of) of his various wives. MG, an only child, had two first cousins, the firstborn a girl, the second a boy. Both the marriages that produced these relatives (they were concurrent) ended, and both mothers, ex-wives of Uncle Nicholas, wound up living within a few miles of each other in New England. They surely knew of one another, but between their children, growing up, there was little, or no, contact. The cousins, evidently never knowing of one another, never sharing Thanksgiving or birthdays or the Jewish or Christian holidays they might have observed each according to the traditions in which they were raised, grew, married, had their own children, and those children had children. Among them are writers, actors, musicians. Those with whom I’ve been in contact either know nothing about their connection to MG, or are peripherally aware. Some are more interested than others in learning more, which is pretty much what you’d expect from people considering a family situation that happened long ago, and with which they had nothing to do. The past is the past. You consider it or dismiss it, it’s up to you. It’s fascinating to me, as I’ve always thought of MG, a childless only child, as being the Hotel Terminus for her family, to know that, via her uncle on the Wiseman side, the line continues. Is that true on her father’s side? Probably, to some degree, at whatever remove. I have no knowledge.

On a January afternoon, Ernst the civilian wears a nylon shirt, a suede tie, a blazer with plastic buttons, and cuffless trousers so tapered and short that when he sits down they slide to his calf. His brown military boots — unsuccessfully camouflaged for civilian life with black Kiwi — make him seem anchored. These are French clothes, and, all but the boots, look as if they had been run up quickly and economically by a little girl. Willi, who borrowed the clothes for Ernst, was unable to find shoes his size, but is pleased, on the whole, with the results of his scrounging. It is understood (by Willi) that when Ernst is back in Germany and earning money, he will either pay for the shirt, tie, blazer, and trousers or else return them by parcel post. Ernst will do neither. He has already forgotten he lived in Willi’s room. If he does remember, if a climate one day brings back a January in Paris, he will simply weep. His debts and obligations dissolve in tears. Ernst’s warm tears, his good health, and his memory keep him afloat. In an inside pocket of the borrowed jacket are the papers that show his is not a deserter. Mavis Gallant, Ernst in Civilian Clothes.

I didn’t know MG, but I’m confident she would have hated this kind of ancestral excavation and exposure. Different scholars — the real thing, I mean — have reported that she would threaten legal action if such and such a postulation linking her life to a story made is way into a paper or dissertation, and she would let it be known in clear terms that she didn’t appreciate anyone sniffing around the traces of her past. The question of the discretion we owe to a writer — or any person whose life is of general interest — who’s past the point of caring what’s discovered and what’s disclosed is a meaty one. I expect she grappled with it in her own writing, and applied it in ways that went beyond the traditional courtesy of identifying — in published diary entries, say — friends and acquaintances by initials, thus bestowing on anyone who might want to dodge identification the gift of plausible deniability. Again, about this I know nothing, but I’m inclined to wonder if the reason MG never made peace with completing and publishing her long study of the Dreyfus case — long in terms of pages and years required to research and write — was because, in her research, she found information that might adversely affect or embarrass friends of or members of the Dreyfus family, some of whom had been her informants. It would not surprise me to learn that a kind of concern or delicacy was, at least in part, in play when she decided to set that long labour aside.

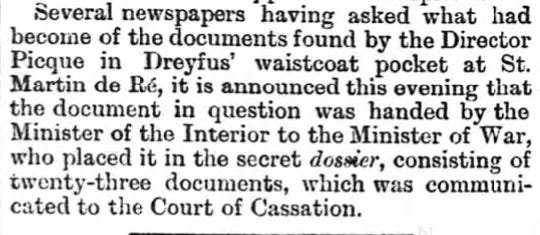

(Writing this just now, I wondered what I would find if I tried to add Dreyfus to my pocket list. It was easily done, from 1899.)

The story of Nicholas Wiseman, the con artist who was MG’s uncle, father to her cousins is alluring, and I’ll continue to tell you as much of it as I know. He’s a compelling and revolting character, as enigmatic as he is loathsome. What happened to make him who he was, someone who was charming, seductive, highly intelligent, but also a thief, a philanderer, and a compulsive liar? MG must surely have wondered, and she would have been supremely well equipped to have answered those questions in fiction. Oddly enough, given that Nicholas was such a womanizer, the characters in MG’s stories whom he most suggests, that most closely resemble someone with such a gift for such arch dissembling, are both gay: Wishart in “Travellers Must be Content” and Walter in “An Unmarried Man’s Summer.” Both are masters of deception, both get by by misrepresenting themselves, and by exploiting the women who sustain them. Both Wishart and Walter — W’s, like Wiseman — are thin-ice walkers, have been so for a long time, moving forward and looking backwards, wondering how far they can get from shore before it all gives way. Did MG have Nicholas in mind when she gave life to Wishart, to Walter? Did she know Nicholas well enough, or know enough of him, or care enough about him, for that to be plausible? Fatuous question —my speciality — for there’s no way to know. In her time on the Mediterranean, over many seasons, she’d have observed and taken the measure of any number of men who were similarly engaged and as transparent in their manipulations.

As noted, among the living descendants of Uncle Nicholas — the once and twice removed cousins of MG — are working writers and actors. Whatever genes compel the creation of art, perhaps, have been passed along and empower them. No doubt nurture (and hard work!) played as significant role in shaping them as did nature. What, then, about something as intangible but as demonstrable as nerve? Is that also woven into the DNA, a kind of family gift or curse, depending on how it's brought to bear on a given situation? Think of Nicholas, the sheer nerve required to perpetrate one fraud after another. Think of Benedictine as a child, fearless, heading up a band of pickpockets, running fencing operations out of corner stores, dressing in her brother’s clothes, age 14, and running away to Toronto; then, a few years later, taking off and crossing the border with Orin Robert Earl, married father of four? These are not the acts of tentative people. Think of MG, betting her future and security against the possibility that she might be able to make her life as a creator of fiction in a foreign country. Timidity in others was a quality she couldn’t bear; no wonder if she was, as seems likely, genetically predisposed against it.

Who cares about any of this? Well. I do. Why? is a perfectly reasonable rejoinder, and, while I’m well-stocked with mere inklings, it’s not a question I’m equipped to answer. Someone else can take that on, if they choose, after I’m dead, and there’s not long to wait! But who would be interested enough? Question réthorique, alors! My own reasons are something about which no one will ever care sufficiently to examine, and thank God for that! My secrets will die with me, and so will my ignorance.

Oh, dearie, dearie me. How self-indulgent this has been, and how grim! My apologies, especially because none of this is what I’d intended to write today. If you look back to the 1850 newspaper clipping about poor Allen and his vial of bedbug poison, you’ll note that his people lived in Lynn, Massachusetts. I’d had it in mind that I would connect that — I laughed out loud when I saw it — to where I left off yesterday, with the promised story of Grover vs Grover, the 1925 society divorce case that rocked le tout Lynn, and in which Uncle Nicholas, then going by Paul Monte, played such an important role. But I allowed myself to get distracted. Ach. So sorry. Tomorrow, then. Or the next day. There’s a gentle snow falling here in southwest Manitoba. There won’t be many more of those this year. I’m going to walk in it, and get all soppy and Robert Frosty. I know where my gloves are, in the pocket where I left them, along with a spare set of keys, and a years-old package of Fisherman’s Friends. Those things never go bad. A bientôt. BR

He said good-bye to his aunt at the station, and added, “If you ask the conductor or anyone to look after me, I’ll — ” Whatever threat was in his mind he seemed ready to carry out. He wore an RAF badge on his jacket and carried a Waffen-S.S. emblem in his pocket. He knew better than to keep it in sight. At home, they had already taken one away but he had acquired another at school. Mavis Gallant, Irina

"These are not the acts of tentative people." Such a sentence! And such an understatement. Speaking as someone who discovered her revered grandfather is a big Amistad, with two families, one unknown to rhe other, I applaud the non-tentative among us. Especially those with well-stocked pockets

Gosh, Bill, your prose style, if one can call it that, is so ... I don't even know where to start, but there IS this: the AI bot assigned to copying your style will have a field day of learning. Sorta like yr artist bot. Nice pics.

In my own style? I love accidental typos, especially when they're really funny. And your accidental Eskimo, when you had intended a perfume-y "intuit," instead was a real howl-aloud moment for me. Now I wonder. Did I even titter? Or was all that celebration in my mind only, just like the inward joy of Isaac Watts?