Grief, Memory, Three O'Clock in the Morning

Putting the Count to Bed, Part 1

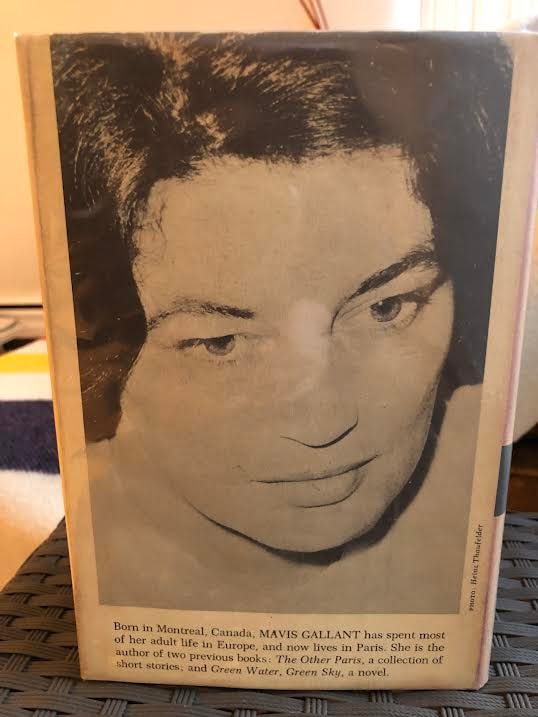

This is the penultimate chapter in the story of Nicholas Wiseman aka Bruce Whitman aka Mortimer Montefiore aka Count Paul Anatole Leon Monte aka Paul Monte aka Paul A. Monte aka Paul Stone aka Paul Wiseman aka Paul-Pierre Monte: the con artist with the multitude of monikers who happened to be the uncle of Mavis Gallant (MG). I’m mindful that I’ve probably tested the patience of readers who don’t share my possibly prurient fascination with a fraud and cheat whose story can only be a tissue of conjecture. One of the great pleasures of adult life is choosing not to read. This is why, on the eighth day, after a much needed rest and a sober consideration of the deficiencies report, God invented “Delete.”

There’s never been a shortage of people like our boy Nick, brilliant and damaged, charming and cruel, self-aggrandizing and pitiable. They are compelling in their sociopathy, their criminality, their pathology, but their train wreck allure is best savoured at a distance, whether temporal or spatial. Proximity almost always means an infection of harm. It’s not true that “every family has one,” not actively in each generation, but rare would be the bloodline where, were you to hoist the rock of lineage, you’d have to stare long or hard to find something — someone — sufficiently squirmy that you’d want to look away and not speak of it in polite company.

Arguably, the whole of MG’s complex, original, and varied work can be summed up as an ongoing attempt to answer the impossible question, “Why do humans behave as humans?” As a young writer, starting out at the Montreal Standard, her first byline, September 2, 1944, was attached to a photo feature about a young boy called Johnny, a neighbourhood kid whom she followed around, accompanied by the talented photographer Hugh (Hy) Frankel. She was 22, just turned, and right out of the gate was writing in what would become her familiar accent. In those round about 500 early words she sounds, already, very much like herself, her curiosity, irony, and penetrative powers in full flight. She writes about the games and bargainings that defined the public hours of childhood in that city and that time; writes about Johnny’s cavalier, dismissive ways with his sisters and mother; writes about his father, away at war. The reader can tell that the writer found her pint-sized subject endearing, with his brassy bravado and sticky fingers and pockets full of half-chewed toffees; but in the choices she makes as a storyteller there’s also the subtle suggestion of a dangerous current, an incipient welling of a more telling, more consequential violence. Nothing but a very few years separate the stones and improvised projectiles of little boys from the deadlier armaments of grown men. As for the impulse that empowers their use, it’s just a question of degree.

Six years later, for her last published piece in the Standard — it was about to become Weekend Magazine — she wrote about another Johnny, Johnny Young, a thief, drug dealer, and thug for hire who was among the earliest beneficiaries of a draconian law that allowed criminals to be named “habitual,” and locked away for an indeterminate period of time, their confinement subject to occasional review on the part of the Attorney General. She lays out the facts of his history — the long litany of crime and punishment — and then writes about what happened to make Johnny Young Johnny Young. It’s very good though not, to my mind, her most accomplished writing; the balance is a bit off, and there are occasional moments of awkwardness, some fissures in the narrative that were probably attributable to editorial ham-handedness, rather than authorial carelessness. Careless she was never, and this was her swan song, a story she would have fought hard for and worked to perfect. Perhaps she wasn’t around to temper the blue penciling; by the time the piece appeared — a cover story — MG was gone. She was already in Paris.

Whether MG spoke of Uncle Nicholas to friends, or mentioned him in any of her private writing, in diaries or letters, I, of course, have no way of knowing. But her weirdly hallucinogenic short story “Rose” — as I’ve noted before — is a clear signal that she knew of him, wondered about him, and assigned him more than face value. What made Nicholas Nicholas? How did he get that way?

In “Rose,” the rogue uncle, the bigamist, is named Hans Thomas.

My uncle was supremely careless, but heaven knows that he hadn't been brought up that way. My grandparents were German. My grandfather died young, and the children were brought up by their mother. My uncle has been knocked about, physically and spiritually, as much as any disciplinarian could ask for. The education of my grandmother’s five children was based on humiliation; when they grew up, they stitched together their torn personalities as best they could. Hans-Thomas had spent whole days in a room, deprived of food and light and air and voices. Regularly, his head was shaved. Since this was not a common punishment in America, it was much remarked and ought to have taught him grace and obedience, once and for all. But he grew up to be just as wilful and heedless as he had been as a boy, hurt his wives, neglected his children, and escaped to Mexico, where he failed in one thing after the other. His mother sent him money until she died.

This is fiction, a story. Hans-Thomas is not Nicholas, but Nicholas inhabits him, plainly. Were the grotesque punishments and mortifications experienced by the young H-T meted out to Nicholas at home? They sound like the stuff of the most loopy Jansenist discipline or like the sadism he might have experience during however many the years he spent in the reformatory. Or, more likely, they are simply part of a fiction, possibly imported from the land of imagination, or possibly a cut and paste job, events transplanted from someone else’s story. Why the name Hans-Thomas? What year did MG meet that other H. T., Heinz Thaufelder — he’s named by his initials in her published journal account of the Paris student riots and, probably, elsewhere in her diaries — with whom she had a long and, as one gathers, not always easy relationship? (As if any long relationship is ever easy!) German, a very young combatant who became a French prisoner of war, which was not a glamorous assignment. Here and there, references are made to Germans living in Paris after the war who get work as consultants or acting in the Word War II movies. Who better to play a Nazi than — well, you know. And Heinz (this is a bit pin the tail on the donkey, but I think this is correct) is a more substantially informing spirit in a number of the early stories — “Willi,” “Ernst in Civilian Clothes,” and “Another Aspect of a Rainy Day,” which were written around the same time as Rose. (The stories from that time make a fascinating suite, tonally and stylistically; they’re wonderfully strange and experimental, which is not to say uncontrolled.) Solitary confinement, head-shaving: were those some of the hardships Heinz endured during his long stint as a POW? And while we’re speculating, maybe there was something about the flesh and blood H.T. — I’m not suggesting criminality! — that reminded MG of Nicholas, or the idea of Nicholas. He claimed to be an inventor — vertical flight was viably developed around the time he was attributing to himself the helicopter — and Heinz was an engineer whose name is attached to patents. Well. This is just straw grabbing, and it turns out to be the kind of straw that reminds you that straw is nothing but the reverse spelling of warts, so let’s just move on. The point is that whether or not the privations and humiliations Hans-Thomas endured and are briefly described in “Rose” were experiences shared by Nicholas, it’s reasonable to look at his adult behaviour and advance the surmise that he was victimized; something happened that dimmed his light, something deadening that left a void where something else could grow, something that wasn’t inimical to darkness. Nicholas was born and Nicholas was made, like anyone else; but what went into the making had a grievous effect.

Before I tell the rest of his story, what little I know of it — and again, my thanks to Linda Granfield who offered many leads and suggestions — I’ll pick up where we left off ten or so days ago and fill in a few blanks. I know that no one has been losing sleep wondering about any of this, but I’d rather see the loose ends tied.

My last writing here had to do with the Grover vs Grover divorce trial that played out in the Salem (Mass.) probate court over 17 days in the spring of 1925. Paul Monte — the pseudonym then used by Nicholas, recently adopted — had been named co-respondent in the divorce suit launched by Lyndon Vassar Grover against his wife, Eleanor Cleveland Grover. It was filed in response to Eleanor’s claim for a separation and support agreement of $50,000. In the end, neither of their wishes was granted. Despite the fact that the marriage was over, the judge granted neither of the disputing parties their wish, and the house of their union was left standing, if uninhabitable. Here’s what became of the principals in that dispute where so much that was so sordid was so publicly aired.

Lyndon V. Grover was a prosperous shoe manufacturer, co-inheritor of the company (J. J. Grover and Sons) built by his father. Paul Monte — that’s how the Grover family knew him — entered their lives just around the time shifts in the economy were bringing about a tightening in the market. Once there had been two factories; then there was one. Changes in the management structure meant that Lyndon, once the CFO, became an employee, the plant manager. The pressures of alimony payments made to his second wife, and the allowance he was compelled to give to Eleanor once the dust had settled, and, no doubt, the scary tab from the lengthy trial, took their toll. Jennifer Peace Willis, Grover’s great-granddaughter, is a genealogist who writes a blog and told the her ancestor's story, making note of a letter he wrote, as she says, “on his deathbed.” He wrote: “But my great mistake is marrying that low, coarse woman—I do not want her at my funeral, or to have her buried with me. There seems to be no legal way that she cannot claim one-third of what little I have left.” He died at the end of August, 1930.

About Eleanor Cleveland Grover I haven’t found much, post trial, and would like to know more. (Not so much so, however, that I’m planning to invest the time and effort into the discovery. To you with failing hands we throw the torch, etc. ) When Lyndon, who arranged to have the inconvenient second wife, Grace, committed, calls the third Mrs. Grover “a low, coarse woman,” we need to consider the source. Eleanor comes off more clownishly than she should in the whole story of Paul Monte, French aristocrat and wrecker of happy homes. She plays a commedia role, the cougar in flapper’s clothes, the lascivious older woman lusting after the younger man, competing with her daughter, Dorothy, for affections that are as oleaginous as they are dubious. This doesn’t do her credit; there was more to Eleanor than that. For one thing, she was by every account a talented actress and was obviously a bohemian with a head for business. Her eponymous theatre company, based in Connecticut, ran for many years.

I admire her, too, for being community minded. Shortly before she and Lyndon married, in 1919, he donated a large portion of his property to the city of Lynn for use as a park. That might have been his own idea — one day he looked up from his ledgers and thought, “I’ll just give it all away!” — but my guess would be that Eleanor had something to do with it. She made her summer place in Maine available as a camp for poor city kids, and was otherwise a collector of strays. I mentioned that she took in a horse who had been forced into retirement when the Lynn Fire Department went all modern. So, about Eleanor, whatever might have been her foolish lapses, there was also the stuff of the redemptory, and more than a little. She lived in New York City after the marriage fell apart, then returned to Massachusetts. She died there, in Melrose, January 7, 1957, age 83.

Eleanor’s daughters by her first husband, Dorothy (b. 1902) and Phyllis (b. 1904) Cleveland, were almost grown by the time she married Lyndon V. Grover and moved to Lynn. The Clevelands cherished, not surprisingly, their family link — distant but real, and via their father — to President Cleveland, whose Christian name was Grover. Quel coincidence, alors! One can imagine the merriment that must have caused around the family punch bowl at the big house on hill in Lynn when the Grovers and the Clevelands gathered for family occasions. It Dorothy, the eldest, who’d played such a pivotal part in the whole unseemly kerfuffle that played out in the courtroom in Salem; Eleanor, for whom Paul Monte was said to have bought a diamond bracelet on the condition that she leave off smoking and swearing. She was married in 1930 to a successful engineer, Roland Henry Baker. They were together for four years, long enough to produce a daughter, Ann, who lived a long and happy life; she died in 2018. About the particulars of Dorothy’s life — it was surely eventful — I can’t say much. She raised her child. She looked after her ageing mother, and then her grandchildren. She did community work. She was engaged to a Brigadier General and World War One hero, Charles Henry Cole, but he died before they married, in 1952. Dorothy quit the flesh forty years later, age 93. Children, take note. A wild youth is not necessarily incompatible with a long life.

It was Dorothy’s younger sister, Phyllis Cleveland — affectionately known as Cookie — who first met “Paul Monte” at the Boston studio where she studied singing. She introduced him to Dorothy, and between them there was a spark. She brought him into the family circle, which probably everyone, with the possible exception of Paul himself, would eventually agree was a miscalculation. Phyllis, very much her mother’s daughter, was a theatre creature, a talented singer and dancer. She was briefly on stage as part of the first Chicago cast of No, No, Nanette — she would have sung “Tea for Two” — but was replaced by a more seasoned performer early in the run, which caused a great deal of harrumphing among her many admirers in the press. Undaunted, she went on to work with the Marx Brothers when they were still Vaudevillians, and then married VERY well, tying the knot in 1927 with J. (Jack) Ainsworth Morgan, heir to a vast real estate fortune in California. That was where they moved — after a six month European honeymoon — and settled down in the Belair neighbourhood. There, Jack wrote screenplays and novels and Phyllis had babies and eventually was the overseer of the Cock & Bull Restaurant, a family enterprise that for half a century was a Sunset Boulevard mainstay; it was the birthplace of the Moscow Mule, a cocktail comprised of vodka, lime, and ginger beer. Phyllis died in 1976.

So, I’ve told you about Lyndon V. Grover and parsed the Clevelands. What about the four Grover children, the products of Lyndon’s marriage to his second wife, Grace Mabel Fuller? It was the youngest of these, Lyndon V. Grover, Jr., who got the bulk of the attention during the trial, but the others were also named during the giving of testimony.

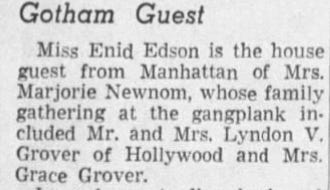

Dorothy Enid was the eldest of the four Grovers. She’d been an outstanding student at the Classical High School in Lynn, very involved in school affairs, and socially adept. She had a chockablock extracurricular life, too; she was accomplished both as a dancer and pianist. She garnered frequent mentions in the local press, was lauded for sweatlessly tossing off tricky salon pieces by Chaminade, say, at various society recitals. Dorothy married her high school sweetheart, Nathan Edson. He was also from Lynn’s mercantile class — the family money was in groceries — and was similarly accomplished and active; he was entering his final year at Brown when they married. Dorothy was old enough that she’d achieved independence and distance when scandal gripped the family. By the time her father’s third marriage began to implode, the young Edsons were making their way in New York. When their marriage, childless, ended, round about 1935, Nathan returned to Massachusetts; Dorothy stayed in the city, moving from apartment to apartment, eventually settling in the Turtle Bay neighbourhood at 2 Bleekman Place.

She was, as I guess, the quintessential post-war career woman, working hard and traveling frequently. (The year did not go by that Dorothy wasn’t aboard the Queen Mary, most usually, sailing to England or some continental port.) Dorothy — not that anyone knew her as Dorothy after she left Lynn — had an amazing professional life. As Enid Edson she enjoyed success both as a painter — she really was talented — and as a designer. She re-invented mattress ticking, for instance — doesn’t sound impressive at first glance, but think of all those mattresses — and applied her genius for the design of packaging to any number of products, most notably for the Old Spice line of soaps and cosmetics when they were first introduced. She held a number of patents for such things as gift box inserts and compacts. She did well for herself. By the mid-50’s she was dividing her time between Manhattan and Bridgeport, Connecticut. (In one census, she’s shown to be living there with a Mrs. Sawyer, but surely not the same Mrs. Sawyer who was called as a witness in the divorce trial of 1925. Wouldn’t THAT be a kicker!) Bridgeport was where Dorothy / Enid died, in her 90th year, in 1989. Plainly, about Enid Edson there is much more to say. Someone needs to write a book.

Marjorie Putnam Grover was the second-born (1900) of the Grover children. Like her sister, Dorothy Enid — and like her mother, Grace — she excelled at the womanly arts of music and dancing. By the time her father, Lyndon, came to visit her in Flint, Michigan, in the weeks prior to his death in 1930, it must have been evident to everyone that Marjorie had erred in marrying Clyde Leslie Newnom. The ceremony — no expense spared, as the Grover circumstances were still a long way from reduced, and Paul Monte hadn’t yet appeared on the scene — took place at the family home in Lynn, in 1921. (Among the guests, and part of the receiving line, were Mr. and Mrs. Thomas Edison. THE Thomas Edison? It would appear so. At first I though this must have been an error on the part of the reporter, and that the name was Edson, the family into which Dorothy Enid had married. But no. It was, indeed, Thomas Edison. WTF? )

On the wedding day, Clyde’s divorce from his first wife, Lillian or Lillie — they had one son — had only just been enacted. He was fresh-faced and gave every appearance of being robust, but Clyde had been dealt a bad hand, constitutionally. He was ill, very ill, chronically ill, and those around him suffered for and with him. If you trace the history of Clyde Leslie Newnom, it’s clear he was in thrall to a serious mood disorder; that he was schizophrenic or bipolar. His is a story of one manic episode after another, all marked by some crazy-sounding scheme, each one more grandiose than the preceding folly. I only know about the ones that made the papers; there must have been many more.

In 1921, he’s mixed up in real estate, selling vast tracts of land in Michigan and also in Florida. “I just need $5000!” he says, in one newspaper ad, and in another he requires the rental of a room in which he can hold a meeting and hang a painting, a really, really big painting! In 1925, Clyde has changed industries and is named as the president of an oil company and is sinking wells in Indiana. No news of gushers ensues. In 1926 he loses his driving licence on a drunk driving charge. In 1927, he launches himself into a career as both a writer or publisher, producing a book of considerable heft (very rare, but copies crop up on the online used book sites) and with the unwieldy title, Michigan’s Thirty-Seven Million Acres of Diamonds. It was a paean to the Wolverine State, meant to start a Michigan land boom. I think.

Most bizarrely, in 1930, Clyde incorporated and became the chief shareholder in something called “The United Go To Church Movement,” which was a Christian inter-denominational effort. It was intended to entice the backsliding population to return to Sunday services and also to raise money for church and mission work. Presumably, somewhere in the charter was a provision for stipends to be paid to Clyde and the other investors, of whom, incredibly, there were more than a few. The main means of achieving this was by the sale of some attractive and colourful commemorative stamps. To read Clyde’s rationale for this venture is to hear a man in the full and terrible grip of what we used to call — and perhaps still do, I’m not up to date with the nomenclature — “a manic episode.” To give him his due, the “United Go to Church Movement” did find some adherents, and a for a couple of years you can locate evidence of congregations here and there, in Poky, Oklahoma, or Dandruff, South Dakota, trying out its tenets and disbursing the stamps. That must have been gratifying, but to say it did not evolve into the epoch-defining movement Clyde had in mind is an understatement of some magnitude. It’s striking to me that the year of this quixotic adventure is also the year Lyndon Grover dies. I very much hope whatever legacy Marjorie might have received was not funnelled into its funding.

As horrifying as Clyde’s story is — the more so because you know it was far, far, far from being unique — you can’t help but admire the guy, even if in a tentative, qualified way. He was, as we used to say, twisted, crazy, boom shooby, flip city, but somehow he managed to persuade himself and the hapless rubes who swam up to his colourful lures that he had something tasty on the hook. Whatever else you want to say about him, Clyde, when he was peaking, knew how to sell. In 1937 he was arrested for swindling someone out of a couple of hundred dollars by investing in a company that was entirely fictional. And that’s when Clyde more or less disappears. I imagine some lawyer with the wits to see what was going on found a way out for Clyde, which was also a way in. As near as I can determine, he was confined to the state hospital for the insane in Ionia, Michigan, and lived there till he died, in 1966. His body was donated to science.

And what of Marjorie Putnam Grover Newnom? While her married life — they had three children, two boys and a girl — surely offered some satisfactions and compensation, it must also have very, very often have been hell. By 1940, she’s in the Los Angeles area. (This was a family pattern. Enid and Elizabeth — see below — stay in the east, but otherwise there’s an extended family exodus for the Sunshine State. Two of the Grover siblings wound up in southern California, as did their mother, Grace, as did Clyde’s first wife, Lillian, as did, for a short time, Nicholas Wiseman. But that’s another story, for the next and final instalment in this saga. I’ll only say that his stay was brief, was interrupted by the law, and as near as I know there was no happy reunion amongst them all, no picnic twixt the redwoods and the crashing surf where they talked about the good times and days gone by.

Marjorie isn’t idle in her new and independent life; probably her circumstances don’t allow her to live as a club lady. She takes a job, genteel and useful, as an interviewer with an agency that finds work for elderly people — I wish such an organization were around today, I would be first in line at the door every morning — and also serves on various community boards. She dies in 1972. I hope she was happy.

What I find most touching about Marjorie’s story is that in 1927, when she was a young wife and mother living in Flint, Michigan, with a husband who was forever flying off the rails and had just poured God know how much money into his publishing venture, she started placing poems in the Detroit Free Press. She wrote love stories, too, that appeared in magazine anthologies such as All-Story Love Tales, and All-Story Love Stories, and Paris Nights. They were entitled, “Don’t Let Me Lose Him,” “Her Name in Lights,” and “A Night Adventure.” Probably, there are others that have escaped my attention. I haven’t read the stories, but the poems, which are very much the kinds of poems that appeared in newspapers at the time, I like. Why should you not read them, if you choose to? Here they are, then, the collected poems of Marjorie Grover Newnom. When things got mad, she made art. I admire that more than I can say.

Diaries were a minor but fascinating feature of the Grover vs Grover trial. Lyndon had kept a journal in which he recorded the details of the many slights he had suffered at the hands of Eleanor and Paul Monte, and he read aloud from it, delighting the well-dressed attendees in the courtroom. The third child, Elizabeth, also kept a diary, and mention was made of it because she confided to its pages — she was teenager — her unhappiness including, possibly, the details of a suicide attempt. Elizabeth — she hadn’t done as well as her sisters at the Classical High School and was a graduate of the Garland School of Homemaking, didn’t get along with her stepmother, Eleanor, who thought that she, Elizabeth, was a bad influence on her own two children, and there had been an unsettling episode at the summer place, in Maine, where Elizabeth and a friend were found in a bedroom with two boys who had apparently acquired marriage licenses and it was all a dreadful mess as you can imagine.

The story’s a bit murky, but Elizabeth survived her age of angst, distanced herself from the fling of the summer of ‘24, and two years later married someone appropriate to a young woman of her standing and station. She and Robert T. Evans — the son of a New York doctor and grandson of Robert Hoe, an extremely wealthy manufacturer of printing presses — had two children, a boy and a girl, and lived in gilded circumstances in Fairfield County, Connecticut. Robert was a successful broker, commuting — in the best John Cheever style — to his office in the city. He retired young and died suddenly at home (I always find that descriptor a bit ominous) in 1962, age 60. Elizabeth continued to travel, in style — this had been a feature of her married life — and died while abroad, aboard the M. S. Vistafjord, not far from Rio De Janeiro, in 1975. She was 71. There was a memorial service for her a few days later, in Connecticut. I’m not sure if she was boxed for return or buried at sea; I hope the latter, for who, given the chance, wouldn’t want to be tipped into the drink while the captain speaks the required text and strangers stop their shuffleboard games as a sign of respect? RIP, Elizabeth.

Finally, we come to the youngest child, to the prodigal son, to the only son, to Lyndon V. Grover, Jr. Imagine how coddled and spoiled he must have been by his older sisters to whom he would have been a doll, by his adoring mother, by the proud Papa whose name he bore and whose business he would surely have inherited had things gone more smoothly on the shoe manufacturing front.

Lyndon Jr. was a handful. This was the boy who was in so much trouble, who riled his stepmother by firing BB’s not just at her but also at the chandeliers; who was found canoodling in the dark in the music room; who was sued for support by the mother of the child he fathered out of wedlock; who had a sideline as a pornographer, taking and distributing nude photographs of young women of his acquaintance; who married early — not the mother of his child — and told the press, who inquired, that he was doing it as an antidote to misery, because he was so sick of all the divorce around him, and then abandoned his wife — she was a cabaret singer — after a few months. The marriage was annulled, his whereabouts listed as “unknown.” Eventually, LVG Jr. surfaced, having migrated west. He paused long enough in New Mexico to marry again, and the newlyweds wound up in, where else, California, in the Pasadena area, where he became the proprietor of Grover Photo. His early interest in shutter-buggery (rude!) paid off. In addition to his “natural child,” Lyndon Jr. fathered a couple of daughters by (I believe) his second wife, then married twice more (once, in Las Vegas, a union that lasted a span of about two months) before he died in 1983.

Of none of these strangers from the past had I heard until Nicholas Wiseman led me there, and it was MG, the sine qua non of this writing, who led me to him; not that she would have wanted him to be found and investigated, I’m fairly certain. The moral is, you never know where fiction will get you. At least one of this Grover vs Grover crew — Edna Edson — could sustain an in-depth biography, and the rest would make a compelling chorus, chanting from the sidelines. Well. So I think. I can’t be alone in feeling that the minor traces I’ve swept up here suggest eventful lives. Fiction, probably, would be the best solution to filling in the narrative. Oh, Bill. Words, words. Too many words. Enough, enough. We’re almost there, children, almost there. There’s just one more player in the drama to be dealt with, and with the next chapter, I’ll put the Count to bed for good. Cheers, thanks for reading, BR

You do know how to spin a yarn!

Who do we lobby to get a Raconteur Laureate? You give me hope for our weary world.