I haven’t written here - or anywhere, come to that - for a long time. As no one has contacted the local constabulary to instigate a wellness check, I assume it’s not a silence that’s churned up widespread panic in the land. Every so often I see a message from a Substack robot letting me know that someone has subscribed to this newsletter - how on earth does anyone learn of it? - and, if you’re a new reader, thanks for the compliment of your attention. You’ve probably gathered that this was a project I undertook to mark the 2022 centennial of MG’s birth. From time to very occasional time, I rise from hibernation to add to it but, mostly, the thing is dormant. There’s been plenty of action elsewhere on the MG front, however.

Like any Friend of Mavis (FOM) I’ve been glad to see so much attention paid to the Uncollected Stories, published earlier this year by the New York Review of Books, edited and with an excellent introduction by Garth Risk Hallberg. The reviews - all farmed out by illustrious papers and periodicals to marquee-worthy names, like Tessa Hadley and Vivian Gornick - have been adoring, and MG continues to be one of those writers who, like sex or debt, an emerging generation feels they’re discovering for the first time and on their own hermetic terms, incomprehensible to anyone whose birthdate precedes their own.

Emily Donaldson, writing in the Globe and Mail, asked an excellent question when she wondered why there was no Canadian publisher for the Uncollected. I wondered the same when I shelled out close to 100 bucks (U.S., darling, greenbacks!) for the pleasure of owning it; more than half of that buoyed the cost of shipment, which suggests to me that it should have been ferried across the continent on a sedan chair borne aloft by oiled Nubians, or wheeled from New York to Vancouver on soap bubbles propelled by the nectar-scented breath of butterflies, but no, it was Wayne, the angry letter carrier, who tried to cram it through the slot, confounded by the physics of the operation, pushing, shoving, swearing, thoroughly rending the wrapping and risking apoplexy before I opened the door and took it from his trembling hands. Ms. Donaldson, demonstrating an investigative rigour to which I wish I’d been heir, contacted Stephanie Sinclair, the publisher of McClelland & Stewart, MG’s domestic aegis-provider, who said that she admired the work the NYRB has done over the last twenty or so years in assigning worthies like Mr. Hallberg and Michael Ondaatje and Russel Banks and Jhumpa Lahiri and Peter Orner to superintend themed gatherings of MG’s fiction, but that M&S had their own plan in mind, which involved engaging a young, hoar-free creative, so far unnamed, to oversee yet another anthology at some point in the fairly near future; someone endowed with sufficient magnetism and unbarnacled bona fides to draw still newer, still younger readers (see above) into the Gallant galaxy, but in a particularly Canadian way. I guess.

Ms. Donaldson, a fine critic and writer, was kind enough to mention in that same review Montreal Standard Time, the selection of MG’s early journalism (1944 - 1950) written for the Montreal Standard. I was lucky enough to work editorially on that book, published by Vehicule Press, along with Neil Besner and Marta Dvorak. (One of the entries, “A Wonderful Country,” the only piece of fiction MG published in the Standard, is also included in Uncollected Stories.)

I can tell you, having spent many, many and once again many, hours squinting my way through every single word the young and enthusiastic and frequently peevish MG wrote for that weekly over those six years, that there’s easily enough for a second volume which might also include the features she wrote for Weekend Magazine, as the Standard was renamed shortly after her departure. And it’s a pity, too, that various pieces of criticism that appeared in The New Republic and the Times Literary Supplement - I’ve read them and they are, as you’d expect, smart and incisive and trenchant - require such effort to track down.

It’s a credit to Mary K. MacLeod, MG’s literary executor, that the file has seen so much activity of late. In addition to the Uncollected Stories, and Montreal Standard Time, there have been reissues of The Paris Notebooks (Godine, with an introduction by Hermione Lee) and her novel, Green Water, Green Sky, (Daunt, with a foreword by Brandon Taylor). None of this would happen without the approval and oversight of the estate. MG’s study of the Dreyfus case, which she began in 1968 and laboured over for a couple of decades but never completed, has been receiving Dr. MacLeod’s forensic attention since 2013 and will no doubt appear before long. That will be a happy day. Perhaps the diaries from the Fifties and Sixties, the publication of which was announced in 2012, two years before MG’s death, will eventually find their way into print. And as for her vast correspondence - well, that would be another and even trickier question.

As noted, I write here rarely. I wouldn’t be making this present incursion, had not MG come recently and inadvertently to mind, via a twisty, unlooked for path. The set up is a bit involved, bear with me. It goes like this. I’ve been poking away at a stupid project which is a collective biography of all the Elizabeth Taylors who weren’t Elizabeth Taylor. (The most prominent of these, latterly, was the English novelist, Elizabeth Taylor, who was MG’s approximate contemporary, born ten years earlier, in 1912. Writer Elizabeth Taylor - her short stories often appeared in The New Yorker - had the misfortune to begin publishing just around the time National Velvet launched the stellar and name-appropriating career of her much younger namesake. For her entire literary career she was “the other Elizabeth Taylor.”)

Taylor is one of the most common English surnames and Elizabeth, though now not so often bestowed, was, for at least three centuries, equally usual. There were, as you would suppose, tens of thousands of Elizabeth Taylors. Most led lives unregistered by any kind of radar but I’ve located a surprising (to me) number who were, in one way or another, extraordinary. The variety and breadth of Elizabeth Taylor’s collective experience over a span of three hundred years is really breathtaking. I mean, the Elizabeth Taylor, who worked as the Manager of Venereal Disease for the state of Nebraska after the First World War, and then ran a tea room manager in Glens Falls, New York, and then just disappeared, is worth her own sturdy volume. I can assure you, too, that Elizabeth Ricketts Taylor, whose poetry and many angry letters to the editor I have faithfully transcribed from Oregon newspapers, is, likewise, a compelling study. I could go on and on; don’t get me started.

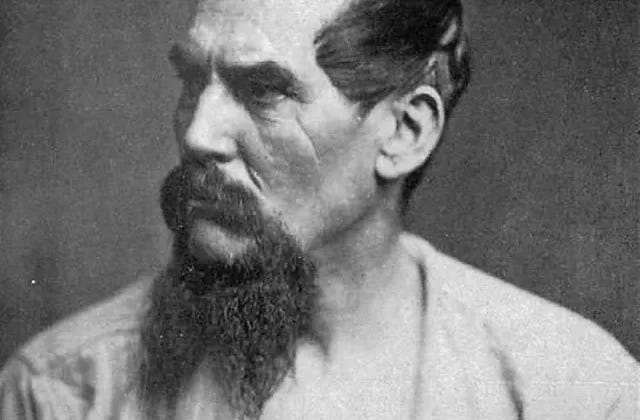

That yesterday I found myself looking for information about Richard Burton had NOTHING to do with Elizabeth Taylor. It was the other Richard Burton, the explorer and translator and Orientalist, about whom I required intelligence, pursuant to a line of inquiry that’s not here especially germane. This search - via old newspapers - landed me on page 6 of the Pullman Herald, a Washington state weekly, for Friday, July 13, 1894. In the column adjoining the one which contained the squib about how the sealed containers of well water Richards Burton had brought back forty years earlier from Mecca (the waters of Zemzem) had been opened and chemically analyzed, I found the following tale, from Kentucky, under the headline “A Girl Tramp Lionized.”

Florence McCurdy, the young girl who was arrested in Paducah, Ky., a short time ago masquerading in male attire in company with a gang of tramps, has captured the town. She sings well, plays the piano with more or less skill, writes a splendid hand and has evidently had good advantages. Her association with the tramp fraternity, however, has somewhat lowered her sense of propriety, and she can sling slang as fluently as the most accomplished hobo. Her home is in Alleghany (sic) City. The women in charge of the Home For the Friendless have interested themselves in Miss Florence and she is being well guarded and taken care of, having been provided with suitable female raiment. Her picture has been taken, and copies will be sold for her benefit. It is also proposed to give an exhibition at which she will appear as an amateur vocalist and pianist.

I was, of course, intrigued, as who would not be? My mind went first to Paris, to Père Lachaise Cemetery, not because Jim Morrison’s stolen memorial bust has latterly been recovered, but because on Gertrude Stein’s headstone Allegheny, her birthplace, was also misspelled, not as above (Alleghany, which is correct for some locales but not in Pennsylvania), but, even more aberrantly, as Allfghany. Whoever chiselled the marble didn’t take the time to proof read. Gertrude, I suspect, would have been more amused than miffed.

MG once, in an interview, cited Gertrude Stein’s Paris, France as a book she recommended to visitors, but that wasn’t the reason she, MG, came to mind. I thought of her because the story of musical Florence, washed up with her good handwriting among the tramps of Paducah, Kentucky, dressed as a man, is so similar to that of Benedictine Wiseman, MG’s mother, who ran away from home in duds appropriated from her brother and was found a few weeks later, going by the name of Jimmy, and singing in a bar in Toronto. This has been well-reported, and I’ve written about it in earlier postings. (There are many, many such stories of girls seeking adventure who cross-dress. Indeed, there are at least two Elizabeth Taylors who did so, successfully, one in the 18th and one in the 19th century. The latter, known as Happy Ned, is a particularly rich tale.)

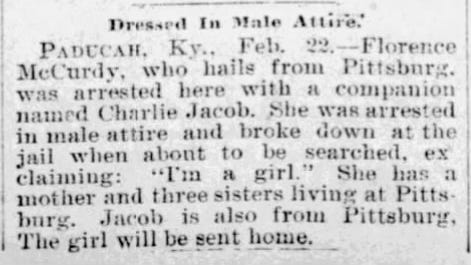

I wanted to find out more about Florence McCurdy and it didn’t lake long to realize that “Alleghany” is not the only misrendering in this short but evocative account of a girl gone astray. She was, in fact, Florence McMurdy, and her hobo adventure was first reported on February 22, 1894.

This article appeared in the Pittsburg Press. (Pittsburgh was Pittsburg or Pittsburgh until 1911, when the “H” stopped being optional. Allegheny City, Florence’s birthplace, was an independent entity until it was swallowed by Pittsburg, or Pittsburgh, in 1907.) This more elaborate account is from the Cincinnati Enquirer, February 22, 1894.

So, here we learn that Charles, or Charley, Jacobs had been a boarder in the McMurdy home, another odd parallel with Benedictine who, seven years after the Toronto escape, ran away for a second time - dressed as a boy scout, according to some reports - and feathered a rural love-nest somewhere near Syracuse, NY, with Robert Orin Earl, said to have been a boarder in the Wiseman home in Montreal. Over the next few days, Florence’s story evolved. Reporters contacted Mrs. McMurdy, Florence’s mother, who let it be known that she was not interested in having her daughter come home. She was a disruptive force and also corrupting; she wanted to safeguard Florence’s sisters from her wanton, worldly ways. She desired that Florence be sent to an uncle in Ohio, where things would be quieter and she could settle down. She herself was thinking about pulling up stakes and getting out of town. Ma McMurdy also denied that Florence had previously been married. Again, there are parallels to Benedictine’s escapade with R. O. Earl. Her mother, Rose or Rosa, when pressed by journalists, weighed in on some of the particulars of her daughter’s story, batting away Benedictine’s assertion that she was a cousin to the German president Friedrich Ebert. (To be clear, I’m highlighting these tenuous coincidences only as curiosities, and am not suggesting anything like a cosmic connection between the two adventuresses. That said, I suspect they would have had quite a lot to say to one another, had their paths every intersected.)

Florence’s costume party with Charles or Charley - romantic, scandalous, louche - made the wire service rounds; was told and re-told all over the country. As the story traveled from newsroom to newsroom, like a whispered game of telephone, the particulars changed and variations emerged; also errors. Florence’s singing gifts might have been emphasized, or the writer might have stressed how the photo of the girl as mendicant did a brisk trade at 50 cents a copy, or the reader might have been told that the prodigal daughter’s mother was happy to welcome her errant child back into the family fold as long the two young lovers agreed to wed. In one version, Mrs. McMurdy — named as Martha, although her Christian name was Arrelia, nee Cochran — has asked Director Grubbs from the “department of charities” in Allegheny if he can offer any financial assistance to get Florence home, but he cannot, and suggests that inquiries be made of cities she might visit along the way, en route home from Paducah, to see if they can help. Which seems a tad loosey-goosey, but I guess that’s how child welfare worked back there and back then.

A minor complication in thoroughly tracking the tale is the way the McCurdy misspelling, the first one I saw, once it was introduced, went unchecked and multiplied. The surname was also susceptible to transcription as McMurdie, which was how it appeared in 1893, the year prior to Florence’s fleeing the coop with Charley, when the father of the family, John, a blacksmith, died at home, age 48. Nor was that the extent of it. Stepping back one more year, to April 28, 1892, we read in the Pittsburg Dispatch that “Edward McCall, brakeman on the Fort Wayne road, [was] charged with felonious assault upon 15-year-old Florence Mutrie, of Lacock street, Allegheny.” You will remember that Edward McCall was the name reported, accurately for once, as appending to Florence’s husband, whom she’d married at fifteen and who deserted her a couple of weeks later; the marriage her mother allegedly denied. Two days later, in the competing paper, the Pittsburgh (with an H) Post-Gazette announced that a marriage licence had been granted to Edward A. McCall and the sinister-sounding “Florence McMurder.” On that same day, April 30, the Dispatch finally got it right when they let it be known that Mr. McCall, age 22, had married Florence McMurdy, “not quite 16. The marriage was the result of a suit brought against McCall. He was arrested a few days ago, and was to have had a hearing yesterday, but the suit was dropped to allow the marriage.” Oddly enough - oddly, as it seems to me - for a wedding that had about it the whiff of the shotgun, it was the recently elected Mayor of Allegheny, H. H. Voegtly, who presided at the ceremony: his first time so officiating in his new capacity as Allegheny’s top dog.

On October 13, 1894, by which time the dust would have settled on her tramping adventure, and apparently back in Allegheny, Florence filed for divorce from Edward A. McCall, citing the grounds of desertion. And then, disappointingly, she goes more or less dark. Charlies Jacobs has exited the picture. Florence married at least twice more. By James Victor Fortune she had a son, Walter Paul Fortune, born July 31, 1896. Florence was then 19; she was born December 4, 1876. We can suppose, though it seems a bit of a stretch, that she is the Mary A. Murdie who is named in the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette as marrying James V. Fortune on May 16, 1896; very much in the family way, I guess. Mr. Fortune, a railway brakeman - just as both Mr. McCall and Mr. Jacobs were railway men, Florence had a fetish - was the son of one of Pittsburgh’s pioneer glass makers. James V. is how his name has come down to us in most of the public records - including his death certificate, 1934, cerebral haemorrhage - but on November 28, 1897, it was a J. B. Fortune who was sent to jail at the behest of his wife, Florence Fortune, on a charge of desertion and nonsupport. I’m not sure when the marriage ended. Their son, Walter, who was a serial bridegroom, died in 1975.

When Florence died, about six months shy of what would have been her eightieth birthday, she was a widow, Florence Tate, and living in, or nearby, Los Angeles. I’m sure there are many more tales attached to Florence, she plainly wasn’t the sort of woman who would hurry to pitch her tent on some plateau of placidity. It’s not clear to me whether or not she knew when she married first Mr. Fortune, and then Mr. Tate, and who knows who else between times, that she was probably a bigamist. She may have filed for divorce in 1894 but it seems not to have been granted. This appeared in the Pittsburgh Press, January 7, 1923.

Edward A. McCall seems not to have remarried - his short bout with Florence must have been enough for a lifetime - and he next turns up in the news in 1946, when he’s 78, and his brother reports him to the Pittsburgh Missing Person Bureau. He just left the house one day, some months before his brother picked up the phone to make that call, and no one had heard from him since. Mind you, he had a history of doing exactly this. Just the year prior he’d disappeared and only got in touch when he ran out of money in Philadelphia, from which city he walked back to Pittsburgh. That same brother died the next year, and Edward was listed among the survivors. That’s the last I know of him.

So - all this came from one quite casual inquiry into Sir Richard Burton, and the proximity of that story to the account of the misnamed Florence McCurdy. Here’s the capper. The last known address of Florence Mae McMurdy McCall Fortune Tate, in Los Angeles, was on Burton Street. You see? It all comes together if you only wait.

Fabulous, Bill. There's a musical in Florence's story.

Oh my gosh, Bill. You have such an eye for the perfect detail. That Florence story is absolutely incredible! Thank you!