Grief, Memory, Three O'Clock in the Morning

Grover vs Grover

I’ve been writing about Nicholas Wiseman, a con man who was an uncle to Mavis Gallant (MG); her mother, Benedictine, was his sister. It’s a story with twists and turns aplenty. Here’s a brief recap, a primer for anyone who hasn’t been following his convoluted comings and goings. By all means, jump ahead if you have the details and timeline clearly in mind!

Nicholas (probably born in Romania, and probably in1896, though 1893 is a date that also occurs, likewise 1899) had a delinquent childhood in Montreal, where the family settled round about 1900. He did a residency in the École de réforme Mont Saint-Antoine (sounds classier in French, esp. with the addition of the italics); his presence was noted there, in the pokey for kids, in the 1911 census. (There are contemporary newspaper reports of an Israel Wiseman, an incorrigible, same age, being sent to the reformatory. One wonders if this might be Nicholas, whose gift for name changing was preternatural and might well have been operative at an early age.)

That same 1911 census is the document that records the presence at home of his brother, also twin, Constantine. Benedictine, their sister, eventual mother to MG, is named as a son (fils) of the family. Presenting as a boy — as Bennie, or Benny — both she and Constantine (or Constantin or Constant) were in and out of trouble with the law, their shenanigans sometimes making headlines.

Nicholas, whatever he was up to, evades, if not the cops, then at least the news, during the time his siblings are picking pockets or breaking into houses or fencing stolen goods. For the duration of the war, Nicholas, in terms of public scrutiny, lies low. In October of 1914, an N. Wiseman is listed among recruits sailing on board the Andania, bound for Plymouth and whatever lay in wait. Is that him? Could be. By 1920 he was representing himself as a decorated French war veteran, a flying ace, and while valour in the battlefield doesn’t much jibe with what we can discern of his character, it’s not impossible that he saw service and even prospered. He was an inveterate, pathological liar, and a skilled dissembler: they do well when times are tough. If he did enlist, and if he went to Europe, it’s not a chapter in his story anyone thought to tell during subsequent court proceedings when his past was up for dissection.

In 1919, in Montreal, Nicholas marries Esther Trattenberg. Round about this time, he starts publicly trying on new identities and gathering new wives. He’s Bruce Whitman in 1920 when he marries Helene Delagarde in Quebec City, and he’s Mortimer Montefiore when, a few months later, he marries Ruth Connolly in Detroit and then, shortly after the Connolly nuptials, Merle Sapp in Texas. Two children are born of these four concurrent unions: Miriam, from Esther; and Bruce, from Helene. (She’ll go by Helen as time goes by, when she settles into her life in New England.)

By 1921, our boy is back in Montreal, identified as N. Wiseman when he’s quoted by journalists writing about Benedictine’s latest scandalous adventure, which was the scarpering off to the woods near Syracuse, NY, with Orrin Robert Earl, married father of four. Benedictine, not shy about giving interviews, was at this time claiming kinship with the German President Friedrich Ebert. Rosa, their mother, denied this, saying, “Where did she get that from? We’re Romanian,” but Nicholas suggested that indeed there was a connection, via their father. Solomon, at this time, had nothing to say by way of confirmation or denial; he was resident in the Hospital for Insane in Verdun, confined there after slitting his throat. Nicholas also reminded reporters that he, N. Wiseman, was an inventor, and that his latest gizmo was a device that enhanced airplane safety.

By 1922 — I may be wrong, but I think this is the date — Nicholas seems to have moved to Massachusetts, to the Boston area. Watertown is his intended destination when he crosses the border at Detroit under the name “Paul Monte Whitman.” He lists his occupation as “chiropodist.” At this time, he’s reunited with his first wife — she’s named as Esther Whitman — and their daughter, Miriam. Boston, the metropolitan area, is where Nicholas and family will roost for the next several years; Winthrop will become Esther and Miriam’s permanent home.

By the time we catch up with Nicholas in 1923, he’s dropped the Whitman and is going by Paul Monte. He’ll have other identities as time goes by, but Paul Monte will be the moniker to which he’ll most reliably return.

As noted in the last instalment of this seemingly endless account, it was as Paul Monte that he appears in 1923 when several papers report that, as a reserve member of the French military, he’s been put on standby to return to Europe to support the French invasion of the Ruhr Valley. It’s as Paul Monte that he makes the news when, while driving, he knocks down and knocks out a 12-year old boy. And it’s as Paul Monte that he first appears in the papers in connection with the family of Lyndon V. Grover, wealthy shoe manufacturer of Lynn, Massachusetts, one of the nearby Boston communities that comprise the “North Shore Colony,” as then it was called. Perhaps it still is.

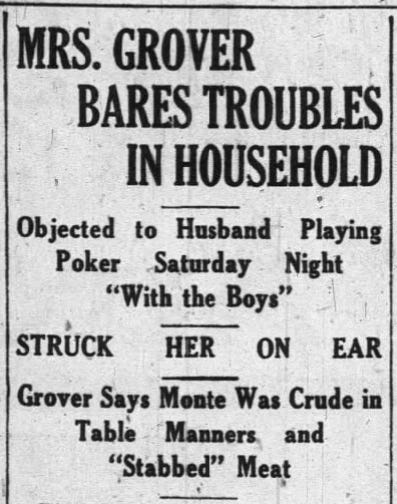

The Grovers were a prominent family. In the spring of 1925, everyone who was anyone in Lynn was gripped by the sordid drama, played out over 17 days in court, of the dissolution of their marriage. Mrs. Grover, the former Eleanor Cleveland, was Lyndon’s third wife; they were married in 1919. Mr. Grover’s four children were well on the way to being grown, as were Eleanor’s two daughters. Nonetheless, the blending of the young people brought tensions — on this family The Brady Bunch was not modelled — and some expected adjustments weren’t made, which proved disappointing, especially for Eleanor. She was miffed that her new husband still liked to play poker with his cronies, especially on a Saturday night when a proper husband is at home, supporting his wife in the staging of her soirees. There were spats, more than a few, and by Christmastime of 1924, things on the home-front had become so heated that Eleanor had had enough. She sued Lyndon for separate maintenance and support. Not one for half-way measures, he counter-sued with a divorce petition. The marriage was a disaster. He wanted to end it, full stop. To do so, of course, he had to show cause, such as adultery. There was a clear candidate for the role of alienator of Eleanor’s affections. Paul Monte (Nicholas Wiseman, but let’s just keep calling him Paul) was named as co-respondent.

The shocking announcement of Paul’s supporting role in the divorce drama was the second time the Monte name had appeared in the news allied with that of the Grovers. The first occasion was in April of 1924.

On April 10, round about 11 PM, Paul returned from a jaunt to the theatre with Mrs. Lyndon V. Grover (Eleanor) and her daughter, Dorothy Cleveland. Young was the evening, and Eleanor repaired to the kitchen to whip up some sandwiches for a midnight snack — a lunch, as it was called, and still is here on the Canadian prairies when a late night meal is served. Paul looked from a window and saw a stranger exit the house from a side door. A thief! He gave chase, but the felon evaded capture. Returning to the house, Paul armed himself with a handy pistol and searched the premises for other miscreants. None was found. The police arrived, and so did Mr. Grover, returning from whatever had been his engagement. He was mystified by how the intruder had accessed the house by that side door, for it had been recently equipped with a very masculine kind of lock, inviolable, and that was because it was via that self-same point of entry that a band of robbers had broken into the house exactly one month prior, March 10, while the family was in Boston watching The Ten Commandments, and had made off with jewelry, furs, and cash. None of the papers reporting that first break-in made any mention of Paul being present, which, in fact, he was. This will come up in the Probate court in Salem over the long and detailed testimony given during the Grover vs Grover proceedings that would take place a year later.

Anyone who wants to follow the trial in all its sordid minutiae can read the details in two organs of record: the Boston Globe and The Daily Item, which was local to Lynn. Both reported the proceedings, and it’s an interesting ontological exercise — for anyone who wants to undertake it, and that can’t be many people — to compare and contrast the accounts of the nameless reporters. The Lynn paper, the Item, is especially good for local colour, and breathless reportage of wardrobe choices and the collective gasps that sometimes animated the proceedings. The Globe is a tad more staid but sometimes discloses details the Item ignores or overlooks. I have read everything both papers found fit to print — it is possible that, at this moment, until memory fades, which won’t take long, I am the world’s leading authority on the Grover vs Grover drama, a bona fide as impossible to prove as it is to monetize.

I will refrain from saying all that I know, for I’ve already tested your patience, dear Reader. What follows is a very condensed version of the highlights of those seventeen days in Salem, 99 years ago.

Again — Mrs. Grover, Eleanor, was pressing, via her attorneys, for separate support. She was seeking a settlement sum of $50,000. Her husband, Lyndon Vassar Grover Sr., was suing for divorce, naming Paul Monte as the co-respondent. Her lawyers would have to prove the affection between Eleanor and Paul was platonic; the opposing counsel would find ways to demonstrate what everyone really wants to hear and already believed, that it was carnal.

Mr. Grover was first to take the stand on March 6. Over the course of his examination and cross examination, the main points that were to be argued and disputed and relentlessly examined and read into the court record over the longest divorce trial ever to be held in Salem would be aired. We hear — not for the last time — that:

Monte was a regular visitor to the Grover home, and not always a welcome one, less so as time went on.

For a time, when things were amicable, he called Mr. Grover “Pops,” and Mrs. Grover “Mother.”

Mr. Grover kept a detailed diary where he noted every affront and suspicion, whether the source was Monte or Mrs. Grover or both.

Monte had a high opinion of himself, even though his table manners were wanting and once, when Lyndon was cutting a roast, Monte stabbed a piece on the platter with his fork.

There was violence. Yes, it was true, he had cuffed Mrs. Grover on the ear after a dispute about bills paid and unpaid — this was a key point in the trial, much analyzed and debated, the slap that was heard all over Lynn, the slap that was much analyzed during the trial, the slap that, after it was administered, made Eleanor realize her marriage was over — BUT she had given as good back when she threw at him a box of popcorn that was a large box of popcorn, by the way, not a small box of popcorn as had been said.

Also, she used bad language, she had called his daughters vile names, and her face would turn black when she yelled at him.

Also, she had taken pictures from the wall to throw at him, she had thrown pillows and shoes at him from a window.

Also, she wrote bad cheques to the washerwoman.

Also, she spat at him.

Here is some ACTUAL TESTIMONY from the trial pertaining to Mrs. Grover and expectorant.

“You didn’t feel the spittal strike you, did you, Mr. Grover?”

“No.”

“Did you see the substance come from her mouth?”

“No. She acted more like an angry cat.”

“After that you still loved her?”

“Yes.”

The Boston Globe reported, in error, that Monte had been present at a Grover family Christmas gathering in 1921; the year was 1923. Lyndon Grover told the court that this was when he learned about Paul’s exotic history / biography.

He was one of the twins of a very wealthy French family, his father being a count; that he had attended the University of Paris and during the World War served as lieutenant in the Aviation Corps and, during that time, married a woman in Russia, who he found was in love with a childhood playmate, a doctor. As he was a French citizen and the marriage had been solemnized by a rabbi all he had to have to dissolve he marriage was a ghet issued by the rabbi; that he had invented a motor and had interested three Boston Jewish people in it to the extent of $750,000 and had sold the motor to England and was receiving a large salary. Monte, he said, declared he had been offered a chance to take charge of the English Aviation Department at a salary of $40,000 a year.

When asked if this seemed to him to be the stuff of fantasy, Mr. Grover concurred.

Over the course of the trial, as Mr. Grover left the stand and Mrs. Grover ascended, followed by her daughter Dorothy, and various family friends and servants — including the chauffeur, there’s always a chauffeur, this one was named “Soucy” — these themes were taken up and variations upon them composed. Eleanor had her first turn at bat towards the end of the day on March 12. When court adjourned — it would not reconvene for several weeks — she promised that, on her return, she would tell “a story that will rock Lynn and the whole North Shore colony. I will tell the whole truth and bare my soul, much as I hate to have to do it.”

In the lead-up to this dramatic envoi — having declined to remove her hat while she give testimony — Mrs. Grover spoke of tensions within the blended families.

She did not, it was true, always get along with the Grover children. There was bad blood between her and Lyndon Jr., because he had objected to the way she criticized him for smoking at the age of 14. He called her “Gyp,” which was the family nickname for her — she had memorably played a gypsy during her time in the theatre — and while she didn’t mind that familiarity, she drew the line at how he had shot BB’s at her, and also at the chandeliers. There had been an episode with a girl, a couch, and a darkened music room into which Mrs. Grover had entered, unaware. (Lyndon V. Grover Jr. would get his own back when he gave his own testimony and spoke of a darkened music room, a couch, his stepmother, and Paul Monte.) Young Lyndon was a handful, for sure, especially when it came to questions of romance. There was a young woman whose virtue he had compromised in a way that could only be settled by marriage, as far as she was concerned. What was more, he had gone to the family summer place on an overnight excursion with another young man and two women without a chaperone, which was because the woman he had asked to be the chaperone was unavailable, and she was also, as it turned out, the same woman of whom he had taken and circulated nude photographs. Young Grover had made threats against Mrs. Grover’s person against which the elder Grover had insufficiently defended her. In the summer of 1924, when she had been away at her camp and had unexpectedly returned to the house in Lynn, she discovered the evidence of many adolescent revels, including the bathtub filled with “soiled blankets.”

The Christmas of 1924 was as difficult as the summer had been. The atmosphere was tense in the big house, even though it had been a small box of popcorn she’d thrown at her husband, not a large one, as per his testimony. Mr. Grover Sr. chose not to eat Christmas dinner at home, offering no explanation for his absence, nor did he wish her “Merry Christmas.” Mrs. Grover was visibly moved on the witness stand as she recollected how she ubraided him.

Don’t you believe in Christmas cheer or Christmas greetings? I told him he had vinegar and water in his veins instead of red blood. I told him money was his God and also told him he would have a little more money to spend on himself and his family if he didn’t spend it on detectives.

Here’s an example of the kind of examination the packed courtroom enjoyed when Mrs. Grover told all.

“When did you really cease to love your husband?”

“On April 7. My feelings had been undergoing a change for some time.”

“On April 6 did you like your husband an awful lot?”

“Yes.”

“On April 6 did you like Monte an awful lot?”

“No.”

“Did you write, ‘I can’t help liking Monte an awful lot.’”

“I might have written it to Mr. Grover.”

…

“Did you tell Mr. Grover after the Washington trip that some day Monte will be able to explain everything?”

“Yes, it referred to his invention and his history, which was bound up with it.”

“You didn’t find out about Monte’s history?”

“That was not my object in visiting Washington.”

“You are now satisfied that the things Monte told you are not true?”

“To what things do you refer?”

“To his family, his supposed title, and supposed education and name.”

To this question, attorney J. A. Farley, counsel for Monte, objected strenuously, but it was allowed, and she answered: “I have not investigated it.”

“Didn’t your counsel?”

“We went to Montreal, if you mean that.”

“You are not satisfied that his name is Nicholas Wiseman; that from the age of three or four year he lived in Canada, and that he never went to university in France and that he was not a count?”

“No, I only have his say for it.”

Over the long, long course of the trial a number of locales are visited and revisited. They include:

The Lynn Police Station. Paul Monte was taken there on the night of March 10, 1924, after the first break-in at the Grover compound. Paul, we learn — this did not appear in the original accounts where he’s not mentioned, he’s only named as the brave fellow who chased down the intruder a month later — was, in fact, on site, and the authorities had reason to believe that he might have been involved in the burglary — which seems to me very, very likely, indeed. However, after a three-hour interrogation they reported that he was either the cleverest crook alive or he was 100% innocent, and they gave him the benefit of the doubt.

Long Island. Mrs. Grover had traveled there with Paul Monte, and it was said that Paul had become involved with a girl he met there. About this, Mrs. Grover had nothing to say, nor would she confirm of deny that she had warned her daughter, Dorothy, against him on their return.

Washington, D.C. Mrs. Grover travelled there with Paul Monte on a short trip, ostensibly to give him a chance to prove his credentials by introducing her to the various highly placed embassy officials whose friendship he was forever claiming, and also to demonstrate something about his invention, which may or may not have been the helicopter. She returned satisfied, but how or by what is never made clear.

A Boston restaurant. Eleanor was observed there along with Paul, and no other person, just the two of them, unattended, and they were talking, eating and smoking. At this she bristled, for she never smoked in public. She kept that for the privacy of her home. With kissing, she had already emphasized, she was similarly discreet. Even with Mr. Grover.

Casco, Maine. Here, Mrs. Grover kept was what referred to as “her camp,” a country estate large enough to require a full time caretaker, and to host 50 “underprivileged children” during that eventful summer of 1954, and for her to give sanctuary to Lynn’s last fire horse when a more modern pump engine was introduced to the fire department and the creature was forced to retire. She was known to be an excellent judge of horseflesh and he was not the only tenant in her stables. Paul had spent an extended period of time there in the summer of 1924, some of it with his daughter, Miriam, though not with Mrs. Monte, i.e. Esther. He was observed in a bathing suit, with Mrs. Grover, also in a bathing suit. They were seen to swim together. They were seen to ride together. He was observed, one morning, in her bedroom, wearing his pyjamas, and they were pink. No one could hear enough about the damn pyjamas.

The Grover House in Lynn. Here, too, Paul was observed in Mrs. Grover’s bedroom, in pyjamas. The colour was not noted. Also observed was Paul’s car and Paul’s suitcase, both in places that aroused suspicion in whoever took note of them.

Paul Monte’s house. Mrs. Grover had once dropped Paul off there, after the theatre. Also, she had once asked her chauffeur to call his number and to report if a Mrs. Monte, of whose existence she’d heard rumours, answered. She did.

Montreal. Mrs. Grover and her counsel were said to have travelled there to interview Paul’s mother. To what end? To confirm his identity, I guess.

Chicago. While Mr. Grover was there on business trip, Eleanor sent him a letter. It read, “Last night Paul took us all out to dinner. He left us afterwards and we went to the theatre. Later one he told us he spent the evening with the son of the French ambassador and the prosecuting attorney in the Teapot Dome Oil scandal. The attorney told him the names of all the big mend including Theodore Roosevelt Jr., and Wrigley, who are mixed up in the oil scandal and said nothing could save them from jail. … I like Paul an awful lot. There is so much good in him and I cannot help feeling that he plays fair.”

New York. Paul travelled there with Mrs. Grover and Dorothy Cleveland when Dorothy required an eye operation. He paid the bill, and was reimbursed. The trip home was via boat. A double stateroom had been booked in Paul’s name, but Dorothy swore it was her friend Mrs. Shaw who accompanied her back. Paul travelled independently. Hours of testimony were devoted to this, and to whether Paul was also a passenger and, if so, where he slept. During the trial, Paul was also photographed there with a silent film star, Juanita Hansen, to whom he was said to be engaged.

A great deal was made, as one might expect, of Paul’s profligacy, especially as it attached to Eleanor and her child Dorothy. Everyone was curious — as they would be — to understand whether it was the mother or the daughter who had the main claim on Paul’s affections. Originally, when he came onto the scene, in the fall of ‘23, it seemed that he was interested in Dorothy Cleveland, age 19. He showed his affection by offering her a diamond bracelet, if only she would agree to stop smoking and swearing for a month. Mr. Grover thought this showed promise. But, over time, it was Eleanor, Mrs. Grover, Dorothy’s mother, who seemed to garner more and more of his attention. He sent her a photograph, lovingly inscribed. Did Paul kiss her? Yes, he did, but only in the way — so Eleanor asserted — a son-in-law in waiting might kiss his mother-in-law elect. Did she know that Paul was married? Yes, he had been up front about that, but had also said that he and Mrs. Monte had agreed to a divorce. There were delays in its processing, no one was quite sure what or why. Documents required. Birthdays to consider. You know. That kind of thing.

And what of Paul himself; “Monte” as he was inevitably named in the reportage? For a while, there was much speculation as to his whereabouts. Registered letters sent to him requiring his presence in court had been returned. Finally, he was located and on April 7, made his first appearance. Then, as on the few other days when he was in court, Paul seemed to enjoy himself, to embrace the theatricality of the adventure. It was what he loved most — a chance for play acting. This is how the Daily Item described the Monte debut in the Salem Court House.

He was dressed in the height of fashion, wearing a blue double-breasted suit and a blue-striped suit, gray topcoat, gray hat, and on his left wrist he wore a watch, and on his right hand he sported two diamond rings. He came to the courthouse in a new sport model automobile of expensive make, bearing New York license plates. In a talk with newspaper men before before court opened, Monte declared that he is prepared to fight Grover’s charges “to the limit.” He said that he had not been summonsed but nevertheless carried with him a briefcase laded down with affidavits to prove that he is none other than “Vicomte Paul Anatole Leon Monte” and that his name is not Nicholas Wiseman and he is not a $25 a week shoe clerk, as has been asserted by those interested in the case.

The Boston Globe notes him “attired in the height of fashion wearing a light grey suit, blue striped shirt. His name was mentioned in practically every question asked by Attorney Underwood, and when Underwood sought to show that Mrs. Grover had advised her daughter, Dorothy, to forget Monte after she returned from a trip to Long Island, he tightened his lips and then clinched and shook his fists in an expression of his dislike of Underwood’s questioning.”

There are several suspensions of the trial before Paul appears again, on May 1, just half an hour before court was scheduled to adjourn for the weekend,

Immediately there was a craning of necks and hushed whispering among the courtroom “fanettes.” “Here’s Monte!” was the byword as the spectators settled back in their seats after glancing at the court-room clock to ascertain just how long Monte would be grilled in the afternoon.”

The dashing Monte, dressed in the height of fashion, and who has been forced to deny his engagements to actresses and young women leaders in the social circles, stepped briskly into the stand. He sat upright in the chair, wearying a gray suit with a red stripe, cut in the prevailing collegiate mode, with bell-bottomed trousers. The shirt was of marbled design with collar attached, and he wore gray silk socks, tan shoes, a pearl stickpin, diamond ring and wrist watch.

“What is your name?”was the first question shot at him by Attorney Mayo.

“Paul Antone Leon Monte.”

“Where do you live?”

“126 W. 33rd Street, New York, and 511 Pleasant Street, Winthrop.” (Note: In the Boston Globe the New York address is given as 126 - 173rd Street.)

Attorney Mayo then questioned him about a visit he made to the Lynn police station about two or three weeks ago. Monte admitted that he made the visit and that it was either on March 23 or 24.

“Where were you born?”

“In Paris, in 1899.”

“Are you a vicomte?”

“Yes, sir.”

“What is a vicomte?”

“A vicomte is a title higher than a count and lower than an earl.”

“Did you inherit the title?”

“Yes.”

“From your father?”

“Yes; his name was Marquis Demonte Fiore.”

The examination is sometimes testy. For one thing, Paul’s counsel has insisted — and this concession is granted — that their client not be asked any direct questions about his identity. He has been summoned as Paul Monte, and who else he might be has no bearing on his connection to the Grovers. He has never represented himself to them as anyone other than Paul Monte, dislocated French aristocrat, inventor, aviator, and licensed chiropodist. He counters many straightforward questions from various attorneys with disingenuous pleas of ignorance. He isn’t sure of the whereabouts of his wife, and declines to say whether he has stayed the weekend at his address in Winthrop; declines as well to discuss he details of his time in New York. He affirms that his mother lives in Washington, but can’t or won’t say where. (To be clear she was living in Montreal. The mother in Washington, he said, was his real mother, not Rose or Rosa Steinmetz or Stone, who lived in Montreal, and to whom he had been given at an early age and who had whisked him away first to Bucharest, then to Montreal. As often happens.)

The reporter for the Daily Item rounds out the week on a whimsical note, describing how Paul’s “testimony was accompanied by music, as a parade on observance of boys’ week at Salem was passing by the courthouse and the strains of the music wafted up through the open window.”

On Monday, May 4, he again takes the stand, “a veritable fashion plate, wearing a dark blue coat, light collegian trousers of bell bottom fashion, white spats, black shoes and sporting a wrist watch, diamond ring, and pearl stickpin.”

His testimony on that day features more unlikely personal stories and a certain amount of prevarication. He describes, to attorney Mayo, his first meeting with Mrs. Grover.

I met Mrs. Grover on one occasion. I told her that was an inventor of the “Montebark Motor” and also a graduate chiropodist and would like to go to Long Island, New York, to see Dorothy, who was visiting there. Mrs. Grover said that people were saying that I was a bootlegger and suggested that I have a talk with Mr. Grover. I met Mr. Grover in the afternoon, had a long talk with him and denied the rumours concerning bootlegging.”

“When is your birthday?” asked Mayo.

The witness hesitated and then replied, “Feb. 2, but I must explain — ”

“Pardon me,” said May, “but I’m asking you a simple question. When is your birthday?”

“Well, if I can’t explain, my birthday comes on May 9.”

(In the version of this exchange that appeared in the Boston Globe this is elaborated, slightly, by noting that Paul had started to add that his birthday was February 2, but after he was turned over to a Mrs. Stone, aka Mrs. Steinmetz, his mother, he celebrated it on May 9. Which still makes no sense, but there you go.)

The court also heard how:

His fondness for Dorothy was genuine, but waned, and that he ceased to caress her on November 24.

He has a certificate attesting to his chiropodist training but can’t access it, possibly his wife has it, it’s hard to say.

He spent 2-1/2 hours with Mrs. Grover in Washington, D.C. having met with various dignitaries earlier in the day.

His slow responses to simple questions he attributes to thinking in French but answering in English.

The following day, May 5, Paul makes his last statements in the Salem court. He bristles when he is described as a shoe salesman; he hasn’t sold shoes for the past two years. He has been devoting his time to inventing a motor and also to writing a novel. Called Pitfall, it was published, he says, in February, 1924. No trace of it can be found. (Later, elsewhere, he would say that it was too spicy for the public to bear, and was suppressed.)

The trial wraps up about a week later. Eventually, the Grover marriage will end, but not as consequence of this long adventure. Judge Dow denies both petitions. He will neither grant separate support, nor a divorce. There are reports in the papers that the Grovers are living together, uneasily, under one roof. Which seems cruel, for all concerned.

The courts have not yet finished with Paul Monte, however. I’ll tell you the rest of his strange, sad story the next time. It begins here.

You have indeed outdone yourself. Who will you cast as Paul for the movie? Mavis must be lying on her back, kicking her heels in delight!!!

Such a good tale. Can't wait for the conclusion. And those cartoons are a hoot. I remember reading the Alexandrian Quartets in my teens; those books were so big then.