Grief, Memory, Three O'Clock in the Morning: June 21, 2025

The Balance Sheet of Elizabeth Taylor

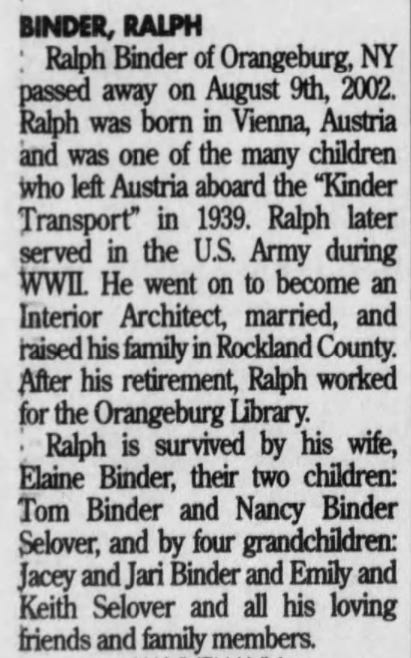

I’ve written before about the irony of how this obituary for Ralph Binder was published in The Journal News, White Plains, New York, on August 11, 2002, Mavis Gallant’s (MG) eightieth birthday. I wonder if anyone thought to let her know about his passing. For such news, she would have had feelings.

To review: in 1940, when MG was seventeen and Ralph was sixteen, they lived together as guests in the home of Henry and Antoinette (Anne) Quackenbos. Henry was a psychiatrist. Anne (nee Price), twenty years his junior, was in her mid-forties when they married in 1938. Maybe they met through medicine; Anne had been a nurse. Personally, as well as professionally, she looks to have been a nurturer, a mender of broken wings. Newly-wed, middle-aged, it would have been enough to close the circle, to adhere to a council of two, to burnish the union; but no, unto her bosom Anne gathered the wounded, adopted an infant son, Nicholas, and tenderly embraced Ralph, an Austrian Jew spirited out of Europe via the kindertransport, and likewise gave succour to MG, the daughter of a friend, headstrong, spookily intelligent, hungry for independence, and with an impressive body count when it came to schools attended and discarded. It was in 1940, in the village of Middleton, in Dutchess County, in the care and keeping of clan Quackenbos, that she would wrap up her formal education. Look. Here she is, smudgy but recognizable, second row, second from the left, with the other members of the senior class of Pine Plains Central School.

It couldn’t have been long after this photo was taken that MG struck out on her own, returned to Montreal in that first summer of the war, presented herself at the offices of the Montreal Standard, informed them she was ready to write, and was told by Philip Surrey to return when she was twenty-one which, duly, she did. Ralph Binder’s sojourn with the Quackenbos wouldn’t have gone on much longer. His parents managed to make their own escape, and settled in Manhattan, upper west side, where Ralph joined them.

Ralph’s middle name was Paul, and Paul was the name MG chose for the German refugee boy who shares rural Connecticut quarters with the Mavis-like Madeline in MG’s first published New Yorker story, “Madeline’s Birthday.” Both young people have been uprooted, Paul by the war, Madeline by the absence of her flighty mother. They’ve been temporarily, and not very successfully, transplanted into the gracious country home of Anna Tracy, an Antoinette palimpsest. It’s an unsatisfactory arrangement for all concerned, but at Mrs. Tracy’s kindly insistence they work at getting by.

Independence, self-sufficiency, emancipation: a composite of those conditions is the light towards which Madeline bends, and it would have been very surprising if the same were not true of MG, at the same age. Nor is it an unreasonable leap to suppose that when MG wrote that cornerstone story - moonlighting as a fiction writer in her off-hours from the Montreal Standard - she drew generously on her time chez Quackenbos, in the horsey precincts of nearly Connecticut New York state, in what would be the last year of her life lived under anything like third party supervision.

1940. What a year that must have been for MG: seventeen, hormones in wild rumpus, fostered out, new kid on the block, last year of high school, the imperative of decision making and future planning. It a tumultuous time in the world (when is it not?), but she would have looked at it, understood it, differently from the other twenty-five soon-to-be graduates. What did they care about the war? Pearl Habour was two years away, but she was from a country already in the thick of it. Years later, she would remember how her peers at Pine Plains Central thought of her as eccentric for keeping scrapbooks filled with clippings about the European conflict. But boys her own age, some she’d known as children, were giving their lives. As well, she had from her mother a Jewish bloodline. Ralph Binder was the living embodiment of what that meant on the continent from which her grandparents had come, not even fifty years before. She had a German speaking grandmother, had been given German lessons as a child. Nothing about it was straightforward. There was a lot with which to grapple.

The details about MG and Ralph and the Quackenbos family are recorded in the 1940 U.S. census. It’s information I’ve shared before, and it only comes once more to mind because - here we go again! - I’m doing some digging into the lives of the Elizabeth Taylors who weren’t Elizabeth Taylor. One I’ve latterly met shares some Venn points of intersection with MG, and is named in that same census.

This Elizabeth Taylor, in 1940, had washed up in Chicago. She was a lodger, one of eight, sharing quarters in the Cleveland Avenue home of Joe and Marie Burmaster (that surname may not have been accurately recorded) and their two children, Otto and Olga. Her rent was twelve dollars a month. Her occupation was listed as “investigator,” an intriguing designation, but vague. Private investigator? Independent researcher? The details are not disclosed, nor do we know when she began her tenancy. It’s safe to posit it wasn’t long-term, and we can also suppose she might have stood out, a little at least, on whatever occasions all the roomers gathered together and talked. Neither of the Burmasters attended school after fifth grade. Only one of the lodgers had completed high school - most left in the eighth grade - other than Elizabeth Taylor, who had graduated college. It would have been plain to anyone with the will to imagine that here was someone with a backstory; someone more to the manor than to the rooming house born.

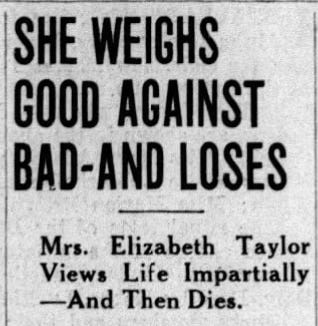

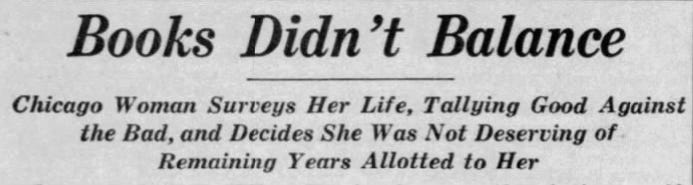

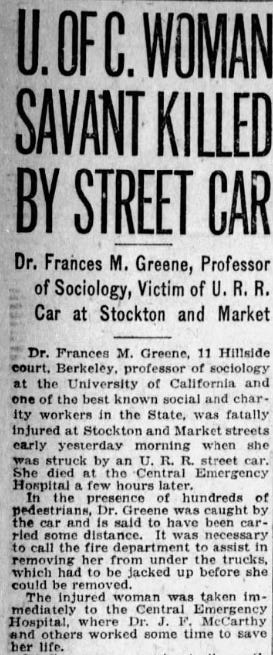

The news of Elizabeth Taylor’s passing on August 12, 1940 - one day after MG’s eighteenth birthday - was widely reported. It was a tragic death treated not quite gleefully but, certainly, as a curiosity, a novelty, page 3 stuff, keeping company with the stories of goats born with two heads and the juicier adulteries. Here’s a small but representative sample of the headlines.

Elizabeth Taylor swallowed sleeping pills. She left behind a kind of rationale for her actions; a “balance sheet,” as it was described. Her note, heartbreaking, was excerpted, in greater or lesser part, in the more than 50 papers that told the story of her suicide. I’m pretty sure this is the text in its entirety.

Here I am, a woman of 41, with a probable 15 or 20 years of active service ahead of me, as a conservative estimate. But first, what am I? Assets - Long line of forebears noted for loyalty, for clever diplomacy, courage, ability to endure - and survive - sustaining suffering and hardship; an iron constitution inherited from the above; extraordinarily brilliant mind. (It is not conceit for me to admit this proven fact since I did not make my mind; it would be, on the contrary, blasphemy for me to deny the possession of any of these tools which my creator has, for his use, placed under my control. Liabilities: Mistakes of several years’ standing which must be lived down…somewhat clouded by several physical ailments. What do I want to do about it? What am I going to do about it - today? Tomorrow? Next week? Self-contempt, weakness, and fear suggest that this time, this place does not need me, and subtly tempts me with the thought that no time and place ever will; that God cannot use - ME!

The heart breaks and the mind wonders. Who on earth was she, this fatally disheartened woman with her brilliant mind inherited from her notable antecedents? I’ve found out enough to say with certainty that her life was strange, sad, and complicated. Well. Many are. If you persist in reading, you’ll see how the telling of her story would benefit from a flow chart or spread sheet. I’m incapable of generating such amenities, so I’ll stick to a bald narrative and do my best to make it as short and simple as possible.

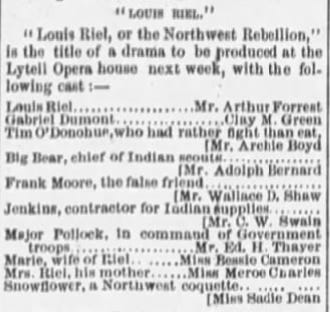

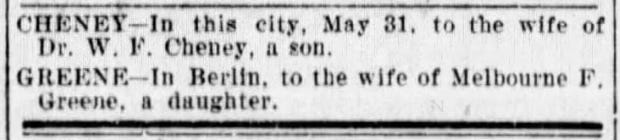

Elizabeth Eva Frances Greene Taylor was born in Berlin, June 3, 1899. Her parents, true to the suggestion in her farewell missive, were, each in their own way, unusual and several cuts above average. Her father was Francis Melbourne Greene. He was born in San Francisco to a pioneering family that became VERY well-to-do; they were the builders of a landmark residence, one of the first houses on Telegraph Hill. Among his siblings were his brothers, Harry Ashland Greene, an inventor, an innovator in the development of radio, and a real estate baron who more or less built Monterey; and Clay Greene, now (I think) mostly forgotten but in his day a shining star, an immensely successful and prolific playwright and journalist. Clay Greene’s success arrived early, waxed mightily, and never seemed to waver or wane. Triumph piled on local triumph and by the time he was in his thirties the west coast could no longer satisfy or contain him. His reputation preceded him when he moved east, and in short order he was doing even better for himself in New York. His illustrious career there - he would eventually return to California to capitalize on the burgeoning picture show business - included a commission (I’m not sure from whom) to write a play that premiered at the Grand Theatre in London, Ontario, New Year’s Day, 1886: Louis Riel, or The Northwest Rebellion. This was six weeks after Riel was hanged - a remarkable turnaround that speaks to the rapidity of Mr. Greene’s production. About both brothers a great deal could be said, but that’s not my purpose here. You get the drift; they were vraiment quelque chose.

Their younger brother, Francis, Elizabeth Taylor’s paternal sine qua non, was an odd duck. Early on, he seemed destined to follow in Clay’s histrionic footsteps, having written a few parodic lyrics for varsity shows. His was a small gift, however; it would never match that of his brother. Francis settled on the career of art historian and critic; a vocation much like harpist or equestrian in that it’s rarely claimed by those abstracted from privilege. Francis earned his living, to the extent that he was required to do so, by giving illustrated public lectures about the life, work, and times of the great painters; and about the state of art criticism. “Art in the Light of the New Criticism;” “The Function of Art in the New Education;” and “The Nature and Scope of Art in the Light of the Newer Criticism,” were among the titles of his talks, which I’m sure were crowd pleasers. (2)

Francis, as anyone engaged in his line of inquiry would have done, pursued his studies in Europe. He was gone from the Bay area for years at a stretch, toured about the galleries and museums and ateliers of London, France, Belgium, and particularly Germany: hence, his presence in Berlin on June 3, 1899; hence, Elizabeth Taylor’s advent there.

Note how, above, Francis Melbourne Greene is identified as Melbourne F. Greene, one of the many small but annoying wrenches thrown into the works by careless and obscuring compositors intent on tripping up future biographers. Nor is that the whole extent of the muddling, for Francis was Elizabeth Taylors’ father, and Frances was Elizabeth Taylor’s mother. One of the challenges for anyone sorting out the unfortunate woman’s story is that this homophonic coincidence occasionally led to confusion in reportage. In some news accounts (they were often in the papers), Frances appears as Francis while at other times Francis appears as Frances. Now and again, the doings of one were outright reported as the doings of the other.

Elizabeth Taylor’s mother was born Frances Rosenberg, also in San Francisco - Berkeley, actually - in 1863. Frances married Francis in 1892. He was her second husband. (You might want to be sure you’ve got a rainbow array of pencils handy, the better to take colour-coded notes.) Her first spouse (1884) was E. Buchanan Marx; the E. was for Esias. Perhaps with assimilation in mind, the Marx children - he had many siblings - were given Hebraic first names and “socially acceptable” middle names. E. Buchanan’s twin was the wonderfully sonorous David Breckenridge Marx. Breck, as he was known to friends and family, died in his 20’s. It was in his honour that Frances and E. Buchanan named their son Breckenridge David Marx.

Frances Rosenberg Marx was a woman of more than usual grit. A measure of her tenacity and verve is that in 1889, while caring for the infant David Breckenridge, she was one of two women graduates in medicine from the University of California. That same year, E. Buchanan, just thirty-three, followed his twin’s example and died. For a few years, Dr. Frances was a single working mother. Then, who knows how, Francis Melbourne Greene entered the scene. They married in 1892. He was Episcopalian, she was a Jew. How that went down with their families is anyone’s guess. If there was disapprobation they escaped it by going to Europe. As noted, Elizabeth Taylor, the only child of that union, came along seven years later in Berlin, a half-sister not to David Breckenridge Marx but to Breckenridge David Marx, by then known as Breckenridge David Marx Greene. (3) I hope you’re following all this.

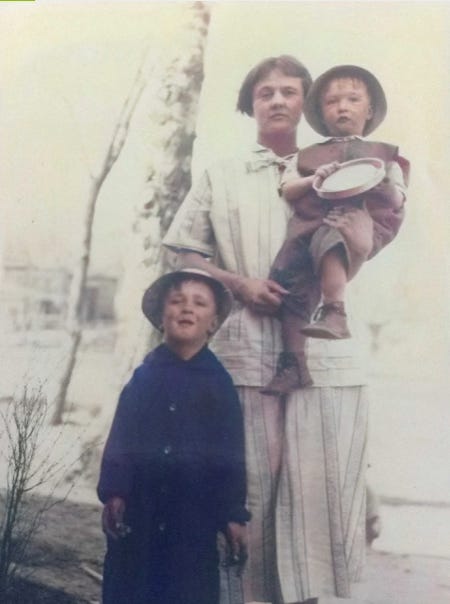

Elizabeth Greene - as she was known for the first twenty-two years of her life - must have had a less than usual childhood, drifting back and forth between California and Europe; between the east coast and the west. This would be my surmise - how could it have been otherwise? - but about those formative years I find little in the way of substantiating information. We know that before she made her first and last big public splash, in that Chicago boarding house, August 12, 1940, she had spent twenty years in Huron, South Dakota, a small city of about 11,000, most celebrated as the site of the “World’s Largest Pheasant” statue. Elizabeth Greene, daughter of Frances and Francis, moved there in 1921. That was the year she sloughed off Greene in favour of Taylor, a consequence of her marriage to Eugene Cowles Taylor. Eugene (named for his mother, Eugenia) was the scion of a prominent Huron family; his father, Alva, was a judge, his mother as close to being a club woman as a town like Huron would allow. They had two boys, Alva and Edward. Here they are.

Eugene Cowles Taylor was, the evidence suggests, a gentle, possibly ineffectual soul. Bookish, he’d studied English at the University of Wisconsin, then Harvard, from which he never graduated. He had sufficient credentials to secure some kind of position in Lincoln, at the University of Nebraska. Delicate of constitution, Eugene was badly stricken by influenza after the war, and never quite recovered. Unable to withstand the rigours of conventional employment he returned to Huron and seems to have lived with his parents - along with Elizabeth and the boys - engaging in what his obituary described as “literary work.” That obituary was written in 1928, just a few weeks after Elizabeth Taylor had addressed a local discussion group, the Fortnightly Club on the subject of “Delinquents and Crime.” It was her contention that deficiencies in parenting, as well as practices of punishment, were responsible for an uptick in juvenile criminality. I wonder if, before launching into her talk, she laid out her own bona fides, and told the Fortnightly Club a little bit about her upbringing.

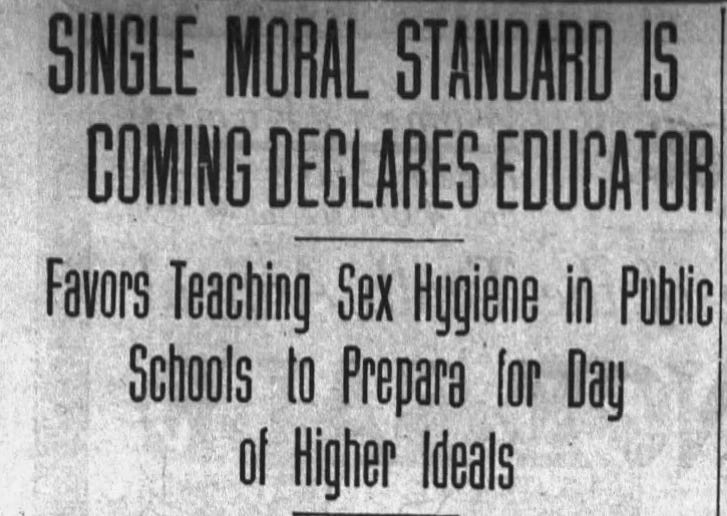

Remember Frances Rosenberg Marx Greene, Elizabeth Taylor’s ma, the doctor? Not long after her daughter was born, she began to set aside conventional medical practice and to build for herself a name as a crusading social hygienist. Working with such agencies as the YMCA, YWCA, and YMHA, she toured about delivering lectures with titles like “The Responsibility of the Mother Toward Her Children,” “Sincerity with Young People,” “Habit and Will,” and “Health and the Delinquent Child.” She served a term as the chair of the California Social Purity Association. When, in this capacity, she spoke to the House of Churchwomen organization, it was reported that “the doors of the room [were] locked and only members of the House permitted to listen.”

In 1910, in Oakland, Mrs. Dr. Frances Marx Greene (as she was usually named) spoke on “The Scientific Aspect of the Education of Children.” The Alameda Evening Times Star described it thus:

Ignorance, declared Dr. Greene, was the cause of much of the suffering, both mental and physical, among men and women, and she said that mothers were often more anxious to determine the financial condition rather than the physical well being a husbands for their daughters. She recalled how, under the auspices of large medical and science associations of the United States and of foreign lands, a movement was on foot for a more complete education of the young with respect to the perpetuation of the race and the elimination of disease. The movement, she said, was to be extended through the factories and department stores. That the work might be universally effective, the mothers were asked to aid by answering their children candidly when they insisted upon Schopenhauer’s expression of ‘the will to live.’

Mrs. Dr. Frances Rosenberg Marx Greene, as perhaps you can divine from reading between those lines, was very much on the side of eugenics. No judgement. Many were. She took her message of social purity to the east coast round about 1912. Elizabeth and Frances and Francis - you remember, he was her second husband - set up shop in Cambridge, Massachusetts. There, Frances gave many speeches on social purity, delinquency, and child rearing, and Francis addressed, as was his wont, anyone who would listen about the history of art. It was during the Greens family’s time in Cambridge that Eugene Cowles Taylor came to Harvard, following his roommate from the University of Wisconsin, whose surname was Marx. Presumably, he was in some way kin to Frances. What’s certain is that Eugene met Elizabeth. They corresponded after the Greenes returned to San Francisco in 1917, and it was to San Francisco that Eugene hurried in 1921, to offer Elizabeth consolation when her mother was killed after being dragged under a streetcar.

“Fractured skull” was the official cause Dr. Greene’s death, though the more graphic reports of the accident (more than a few) made it clear there was a lot of below the neck trauma. A terrible, terrible time. Eugene must have said all the right things.

Reader, she married him.

They went to South Dakota, to Huron. Babies were born. Eugene died. Elizabeth, widowed, was on her own with two young boys (4) and in-laws who may or may not have been fond of her. She stuck it out for ten years. In 1939, probably, she’d reached the end of her tether. She went to Chicago, found cheap lodgings, hung out her shingle as an “investigator.”

Reader, we know the rest.

We don’t know, though, what happened to Francis Melbourne Greene. Perhaps, after his wife’s tragic death, he escaped, went to Europe, sought solace in art, as he’d often done before. We know that in 1930 he was back in California, with a part-time appointment teaching extension courses in art history a U.C. Berkeley. That’s the last we hear of Francis. When his two famous brothers died, both in 1933, his name was not mentioned in their otherwise extensive obituaries. Francis is one of the gifted vanishers. He made himself invisible. He is, and will probably remain, a mystery.

I wrote that Elizabeth Taylor reminded me of MG, and this is one of the points of coincidence: the artistic father who sinks without a trace and leaves a gap, a lingering wound of uncertainty. Like MG, she had an extraordinary, intelligent, and in some ways outlandish mother. I wonder, too, about what it was like for Elizabeth, with her exotic parentage, her Jewish heritage, in a small, conservative city like Huron in the 1920’s.

The Berlin to Chicago story of Elizabeth Taylor, 1899 - 1940, exists in fragments, fleeting glimpses glancing off of shards of mirrors. It would be best told as fiction, but not by me. To the hands of some master, I consign the task.

On August 11, 1940 MG was in Montreal, marking her eighteenth birthday. What did she write on that day? Something, surely. Perhaps someone, somewhere, knows. On August 11, 1940, Elizabeth Taylor had made up her mind. She had her bottle of tablets. She had her paper and pen. She sat in her room. She wrote her mind. We can read her words still, hard though they be. “God cannot use - ME!” This is sure. Two women who never met, one 18, one 41, on the same day, had the same thing in mind. Freedom. Only freedom. They got what they wanted, each in her own way.

And that is as much as I can say about it.

NOTES:

(1) The Quackenbos later lived a few miles from Middleton, NY, in Sharon, Connecticut, in Litchfield County. James Thurber lived in Litchfield, which hints at an answer to a question I posed in an earlier post about how MG knew, as she did, if only in a passing kind of way, Thurber. Also present in the household during that year in Dutchess County with Antoinette and Henry was the infant son they had adopted, Nicholas Cyril; they would later adopt his sister, Nancy. No doubt MG, whose position the census taker noted as “servant,” was called upon to provide baby-sitting services. Perhaps it was this experience in part that informed her later feature writing work for the Standard where she freely and feeling spoke her mind about the comme il fauts of child rearing.

(2) I’m not concerned at all with THE Elizabeth Taylor but I’ll note that her father was also Francis, and was also in the art world, as a dealer. He did very well for himself owing to his connection to Augustus John, and general business savvy.

(3) Breckenridge David Marx Greene is his own vast story, a prominent and notoriously truculent attorney in the Bay area. He died of a head injury when he slipped on the terrazzo tiles of San Francisco’s city hall. His surviving daughter, Elizabeth Taylor’s cousin, was Elizabeth Marx Greene.

(4) The two boys had what seem to have been happy lives. They served in the US Navy during WW2. Afterwards they set up Taylor Films, a production and distribution business. (The photographic adjacent arts were very much in the family. Harry Ashland Greene was an innovator, as was his son, and Francis Taylor, for all his goofiness, made pioneering use of stereopticon slides in his lectures.) Alva Melbourne Taylor, named for both his grandfathers, attended seminary, became a Protestant missionary. A United Church of Christ minister, he also served as a psychiatric social worker. He died in 2011. Edward Cowles Taylor stayed in Huron, continued in the AV business. He died in 2004.

Look what they found at the old Quakenbos residence. Maybe Mary Grace Quackenbos’ belongings where returned to her previous husband? I've also wondered what connection or why the kids would end up with Henry. It seems henry may have been ‘working’ and needed a family to keep up appearances?

https://www.tiktok.com/t/ZP8BaXyn5/