Grief, Memory, Three O'Clock in the Morning

Ex Libris Mavis Gallant: Gardening in Sunny Lands, 2

(In these occasional entries — this is the second — I review books mentioned by Mavis Gallant in her fiction and journalism. “Gardening in Sunny Lands” was a book she invented in her short story, “In Italy.”)

Mavis Gallant’s “Thieves and Rascals,” published in 1956, is one of those rare stories not to have appeared in The New Yorker; it was featured in the July issue of Esquire.

Charles Kimber, a New York City lawyer, receives a call at his office from the headmistress of St. Hilda’s, an upper state girls’ school. The news is bad. His daughter, Joyce, is being sent home, banished for having spent a weekend in an Albany hotel with a young man. That he’s from a good school and upstanding family were, as factors go in such circumstances, bolstering, but insufficiently mitigating so as to avoid expulsion. Furthermore, Joyce has chopped off her hair with her manicure scissors. Charles is surprised (a) that his daughter — listless, adenoidal, sloppy — had the gumption to participate in such an escapade, and (b) that any boy would be interested in her. Who is this child, this spawn of his loins, he wonders as he contemplates how to break the news to her mother, his wife, Marian. A model whose reed-thin likeness often decorates the pages of Harper’s Bazaar or Vogue, Marian “groomed herself with the absurd concentration of a cat; and she often sat before a mirror, chin on hand, contemplating, quite objectively, her own image.” Charles won’t be able to tell her till later that evening, as he’s scheduled to dine with Bernice Lawrence, who calls herself Bambi. She’s not much older than Joyce; Charles has had a twice-a-week arrangement with for four years. They meet at her apartment, the better to avoid being seen in restaurants.

In four years, she had complained only once or twice about their secluded relationship. The most difficult argument had taken place after she bought and read Vogue's Book of Etiquette. She had shown Charles the section on Dining with Married Men. "It says it's all right, if you don't do it too often with the same married man,” she had explained.

The first iteration of Vogue’s Book of Etiquette appeared in 1924. A hundred years ago — and where are the celebrations marking this milestone? — the authorship was ascribed to “the editors of Vogue,” although it was largely the work of Caroline King Duer. She retired from the magazine in 1937, after a dozen years in charge of the home furnishings and silverware sections. I append here an extract from her obituary, (New York Times, January 23, 1956), which stirred in me feelings of great tenderness towards Miss Duer.

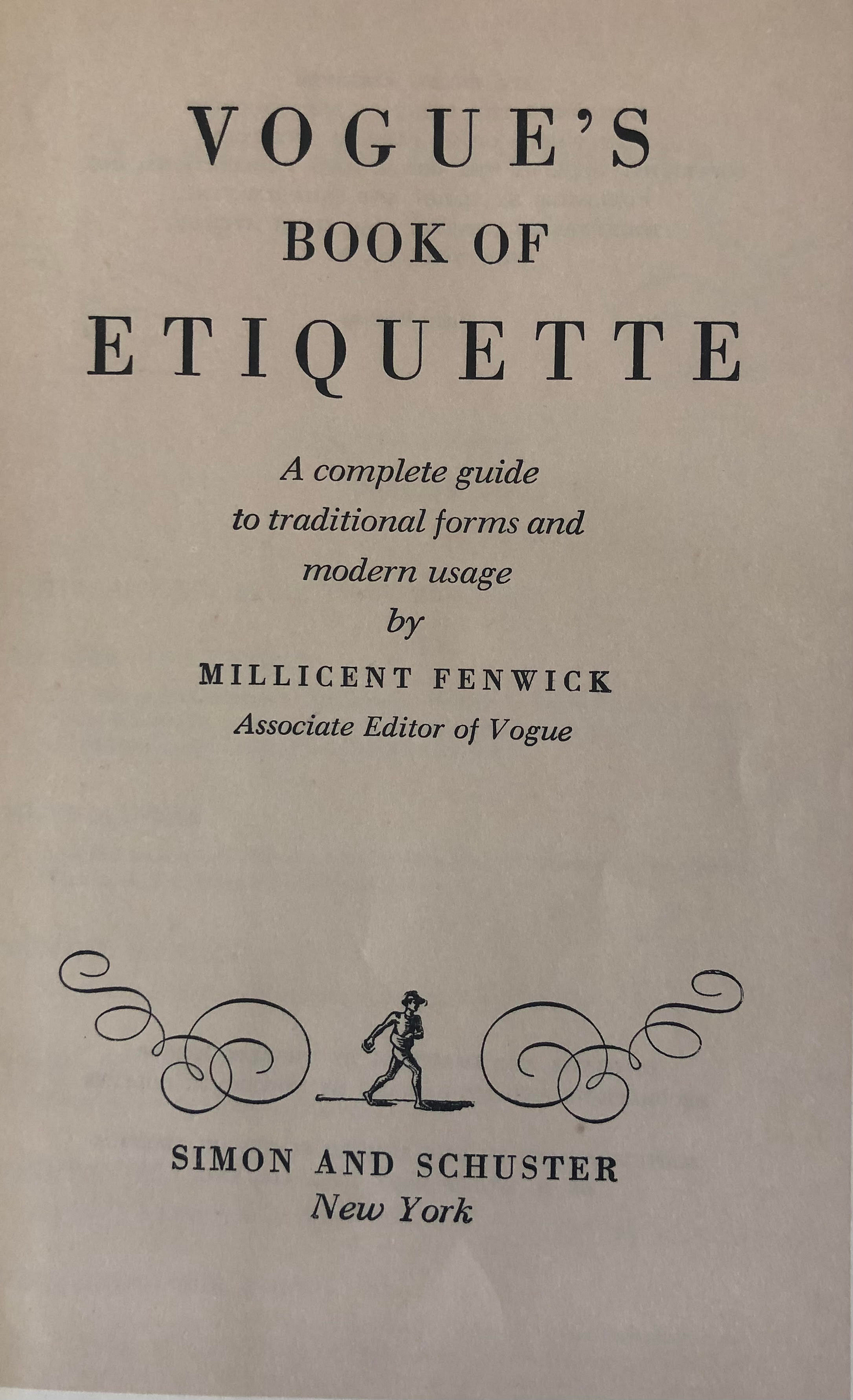

The iteration (there have been several) of Vogue’s Book of Etiquette to which Bernice / Bambi refers in MG’s story was published in 1948. By then, there was no equivocating about whose was the guiding hand; it’s clearly stated on the title page to be the work of Millicent Fenwick, Associate Editor of Vogue.

The passage which disrupts the calm in Bambi’s apartment on that evening after Charles has had the upsetting news from St. Hilda’s is found in Chapter 5, “A Girl On Her Own.” Charles’ young mistress has been paying particular attention to the subsection ominously entitled “Men.” For your interest, elucidation, and possibly your amelioration, I have transcribed the relevant passages.

Here follow two sets of rules for behavior, as far as men are concerned; the first is traditional and conventional, the second, the most unconventional that is sanctioned by modern usage.

The Strictest Set of Rules

a. Never dine alone with a married man, unless his wife is your great friend.

b. Never accept an invitation through a man to the house of someone else.

c. If you have met a man and his wife together, and the man asks you to a party at his house, do not except; his wife should invite you. If she is away, of course, there is no discourtesy implied, and if he invites you to a party, you may accept.

d. Never drink anything alcoholic, except sherry, or a glass of wine with dinner.

e. Never encourage stories that are risque.

f. Never allow a man to come into your apartment if you are alone in it, or stay on with other guests have left.

g. Never go alone with a man to his apartment, or stay on in his apartment when other guests are gone.

h. Never go alone with a man to his hotel room, even if he has a sitting room.

i. Never accept a valuable present from a beau or possible beau — a very old rule and very sound.

If she follows the above rules, no young girl could conceivably be considered fast or cheap. She could never be misunderstood. If she refuses an invitation, a drink, or present in a prim and righteous way, she may be considered stuffy. If she refuses all these gracefully, with a smile, she will be thought charming and well brought up by the world at large and, by young men, eminently wifely material

A More Lenient Set of Rules

a. Never dine repeatedly with the same married man

b. Never drink enough alcohol to be even slightly affected by it. Even this should be limited. "She can certainly hold her liquor "is not a compliment.

c. Never allow a man to come into your apartment, if you are alone in it, except in the daytime or before going out to dinner in the evening.

d. Never go to a man's apartment after dinner hour if he is alone.

e. Never go alone with a man to his hotel room; if he has a sitting room, never go there after the dinner hour.

… and three rules that are unchanged

f. Never go alone never allow a man guest to stay on in your apartment after the other guests are gone.

g. Never stay on in a man's apartment after the other dinner guests have left.

h. Never except a valuable present for a beau or possible beau.

If she follows the above rules, no young girls will be seriously criticized. The more conservative people may question a little and reserve judgment; but although there is nothing immediately reassuring in such a pattern of behavior, there is also nothing startlingly or uncompromisingly unconventional. Eligible young men may be a little more on their guard, a little slower in recognizing in this pattern a young girl’s preeminently wifely characteristics, but for all of the most conservative there is nothing alarming.

The chapter ends with a warning about how men are just as inclined to gossip as are women; possibly more so. Much lasting damage can be visited on a young woman if the whisper network puts it about that she tends to the lubricious. I am so fond of the sentence, “If young girls could hear men discuss women and their ways, they would cling to convention like a limpet to rock,” that I think I might stitch it up on a sampler and nail it to some blank spot on some wall.

It’s easy to poke fun at such comme il faut faire guides as this, but, old-fashioned as I am, and despite Millicent Fenwick’s tacit and now risible assertion that every decision a young woman makes should plump up and draw attention to her wifeliness, there’s a certain common sense quality to her cautions. Mrs. Fenwick(1910 - 1992) was from a patrician, ambassadorial family but knew her share of difficulties. Her mother died on the Lusitania, her father was remote, she never got on with her stepmother, her marriage was a disaster, she raised her children on her own, and so on. She was a very good writer and, after leaving Vogue, entered civic life, and served several terms in Congress. For Millicent Fenwick, I have a lot of time and respect.

One wonders, of course, about the constituency for such a book. The likely audience, which might also be its intended audience, is those who are aspirational, who are bent on class mobility, who have their sights fixed on the upper echelons. Probably, if you’re someone who receives invitations for country weekends at homes where there will be staff with whom to contend, you don’t need to be told, as Mrs. Fenwick discloses, that it’s bad form to say “Hello” to the butlers and maids, for “Hello” is too informal; hence, “Good morning, Marie,” or “Good afternoon, Benton,” are de rigueur. Except, of course, in the evening. At which time one should say, “Good evening.”

More generally useful, perhaps, is the “Scale of acceptable lateness,” which specifies, for instance, that if you’re having luncheon or dinner with another person of the same sex, you may be five to ten minutes late, and that if you’re a woman dining with a man, you may be up to fifteen minutes late, but that if you’re meeting a married couple at restaurant, being more than ten minutes late is cause for striking you from the Christmas card list.

I read, too, with great care, and just as much rue, Chapter 18, with its catalogue of “Misused Words and Phrases.” To wit:

BOY FRIEND should not be used instead of “beau.” There is a further reach in which “boy friend” can be amusingly used — a sort of willful double-twist, implying much more than appears on the surface. ‘He was definitely not the boyfriend type’ would suggest one who lacked a certain open or cozy quality.

DOG should not be used instead of “hound,” meaning one of a pack of hounds. “Dog” is correct in speaking of sporting dogs, such as retrievers and pointers, which hunt separately and not in packs. The only correct use of the word “dog” in connection with hounds is in making a sex differentiation: “The dogs are in this kennel, the bitches on the other side.”

PHONE should not be used instead of “telephone” — either as a noun or a verb.

QUICKIE should not be used instead of “quick drink.” “Quickie” is objectionable not because it is slang, but because it implies a certain shame on the part of the speaker, as though to minimize the fact of drinking.

Please bear this in mind the next time you phone some dog of a boyfriend and suggest a quickie.

There’s a Canadian connection to the Vogue guide which isn’t widely know, nor will it be, I don’t suppose, after I write about it here. It involves a young Vancouver woman; young she was, at least, in 1947. Pat Dorrance (b. 1926) came from a good family — her father, Wallace, was a doctor — and attended good schools: Prince of Wales High School, UBC, and then Stanford. At the latter university she took a graduate degree in Creative Writing. The program was brand new then, was founded by Wallace Stegner in 1946; the only other degree writing program at that time, was, I think, the Iowa Writers’ Workshop. As her graduating project, Pat designed an issue of Vogue that was tailored as a draw for tourists who might be interested in visiting Canada. She submitted it to a contest called the “Prix de Paris,” sponsored by Vogue, and so-called because the winner was awarded a year-long editorial internship in the magazine’s Paris office, or in the New York HQ. Pat won. Shortly afterwards, wearing an ice-blue gown of her own design and creation, she married Peter Calvert Woodward (b. 1917), a scion of the prosperous mercantile and ranching family, well-known in B.C. They moved to New York, which was Pat took up her duties in the Vogue office and worked, under Mrs. Fenwick’s supervision, for Vogue’s Book of Etiquette.

They returned to B.C. in 1963 and made their home in Chilliwack. Peter died in 2011, and Pat in 2020. A nature reserve atop Chilliwack Mountain, a 36-acre parcel donated by her to Hillkeep Regional Park, bears her name.

I never met Peter and Pat, would never be so presumptuous or impertinent (especially not after my immersion in Vogue’s Book of Etiquette) as to speculate on the quality of their shared lives, but the evidence would suggest a solid foundation of happiness, or something like it. Their marriage must have had the usual ups and downs and challenges of any union between two people, but married they were and married they stayed for 64 years. It would be even more fatuous to speculate on the viability of a marriage that exits only in fiction, and a few moments of which are sparsely described on just a few pages, but I suspect the alliance between Charles and Marian also endured, even though MG’s intention in the story is to depict the unbreachable gulf between women and men. All men are rascals and thieves, according to Marian, which Charles denies, quite genuinely, despite having just come from his tryst with Bambi. She’s the one who will surely break free; soon, probably. One can only wish poor Joyce the best, too, once her butchered hair grows back.

One last thing about “Thieves and Rascals” — it’s anthologized in The Cost of Living: Early and Uncollected Stories — and this pertains to Bambi, is that MG gifts her with a quick blink of her own biography. After she has cooked and served dinner — it began with mushroom soup and ended with chocolate eclairs — and as things are getting a tad tense, Charles asks if she, Bambi, when she was his daughter’s age — not so long ago — was interested in men. She replies:

I don’t know what you’re getting at, exactly. I went to a good high school, all girls. Lauren Bacall was in my class. They were all nice girls. We never talked about men. We were interested in clothes, and world events. We had a very superior World Events teacher.

During her time at Julia Richman High School, MG was a classmate — or at least a contemporary — of Lauren Bacall; also Patricia Highsmith. In 1946, when MG was working at the Montreal Standard, her editors played that up that schoolgirl brush with celebrity in a mini-profile of MG that was published a couple of weeks after she’d upset some readers, and delighted others, with a feature called “Why Are We Canadians So Dull?” The facsimile I attach here, a copy of a copy of a copy, is subpar, but legible, if only just. How strange that MG remembers the famously husky sounding actress as having a squeaky voice.

By the way, “Why are We Canadians So Dull?” is among the features included in the forthcoming (Vehicule Press) selection of MG’s early journalism, Montreal Standard Time. It should be in stores round about the middle of October.

Finally, just for the fun of it, here’s Miss Bacall just before she hit the big-time, still going by Betty, keeping company, perhaps not for the last time, with a “beauty connoisseur.” Thanks for reading, cheers, BR

MG; Lauren Bacall; Patricia Highsmith: what a trio!

I think Betty read the column by Mavis and worked on her voice. BTW, I thought Mavis might have profited by dropping a register or so.