Grief, Memory, Three O'Clock in the Morning

New Year's Eve

“Most lives are wasted. All are shortchanged. A few are tragic.”

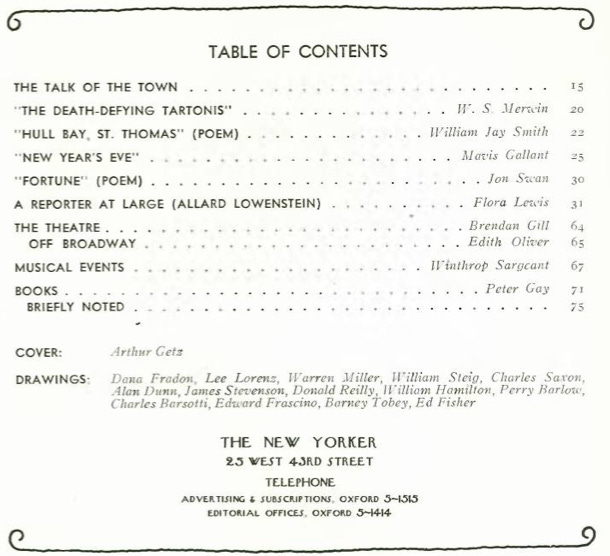

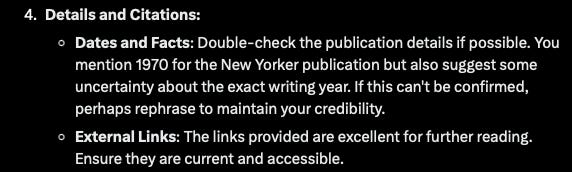

That sunny epigraph is from Mavis Gallant’s (MG) short story, “New Year’s Eve.” Quite when it was written I can’t say, probably 1968 or 69; it was published in The New Yorker when 1970 was fresh and new.

This story about three damaged and unloveable people is not much referred to among Gallantoscenti, but MG thought highly enough of it to include her Selected Stories (1996). In that hefty volume - designed, I’m quite sure, to resemble a family Bible of the “came over on the Mayflower” or “made it into the Titanic lifeboat” variety - MG used two systems of organization. The four groups of stories that occupy the last quarter of the book’s almost nine hundred pages are linked by character or characters: Linnet Muir, say, or the Carette sisters. These stories, considered as a quartet of collectives, give one the sense that at some early stage she had something more extended - I mean four novels - in mind. The stories in the first seven hundred pages of the omnibus are sorted by decade: the Thirties and Forties, the Fifties, and so on, through the Eighties and Nineties. This latter system of ordering reflects either the date of composition, or else the time in which the piece is set. So, “The Moslem Wife,” published in 1976, but set before, during, and after the Second World War, finds its home in “The Thirties and Forties.” “New Year’s Eve” is the last of the ten stories gathered under the rubric of “the Sixties.” I feel sluggish writing this on January 3, but as it didn’t appear in The New Yorker until the 1970 issue of January 10, I could make the case that I’m actually a week ahead of the game. For once.

About triangles, and all geometry, I’m obtuse, and while I can’t call to mind the laws of sines and cosines I suspect they might come in handy to describe the triangle, wonderful in its obliquity, that MG draws here. She sets it out in the first sentence: “On New Year’s Eve, the Plummers took Amabel to the opera.”

As I have not made a resolution to forsake the discursive for the direct - why would I drain my swamp of its only charm? - let’s pause here to admire this roadside cairn upon which is inscribed a Thomas Hardy poem, circa 1901.

Amabel

I marked her ruined hues,

Her custom-straitened views,

And asked, "Can there indwell

My Amabel?"

I looked upon her gown,

Once rose, now earthen brown;

The change was like the knell

Of Amabel.

Her step's mechanic ways

Had lost the life of May's;

Her laugh, once sweet in swell,

Spoilt Amabel.

I mused: "Who sings the strain

I sang ere warmth did wane?

Who thinks its numbers spell

His Amabel?"

Knowing that, though Love cease,

Love's race shows undecrease;

All find in dorp or dell

An Amabel.

I felt that I could creep

To some housetop, and weep,

That Time the tyrant fell

Ruled Amabel!

I said (the while I sighed

That love like ours had died),

"Fond things I'll no more tell

To Amabel,

"But leave her to her fate,

And fling across the gate,

'Till the Last Trump, farewell,

O Amabel!'"

Was MG, in choosing to christen one of her trifecta Amabel, saluting Hardy? That’s a stupid, grasping notion. She might just as well have been giving a fond nod to Bruce County’s Amabel township, or a sly wink at Amabel Williams-Ellis, the Bloomsbury adjacent writer and folklorist / anthropologist who was cousin to Lytton Strachey. Was she remembering the once popular but now obscure nineteenth century romances where Amabel was the titular character - see below, by Mary Elizabeth Wormeley, and it was a bestseller for most of the 1850’s.

Any of these are possible, or MG could just as easily have been invoking the memory of Amabel, Baroness Lucas, an early historian of the French Revolution who posted this advertisement on July 19, 1799, in the Leiscester Journal and Midland Counties General Advertiser:

Burbage Wood

Where as an Oak Tree has been in the Course of the Spring, cut down, and stolen away out of the above Wood, the Property of the Right Hon. Amabel Baroness Lucas: Whoever will give Information of the Offenders, so that One or more of them shall be brought to Conviction, shall receive a Reward of FIVE GUINEAS, by applying to Mr. F. Burges, Attorney-at-Law, at Lutterworth. And as several People must have been concerned in the above Robbery, if any one will turn Informer, so that his Accomplice or Accomplices may be convicted, he shall have the above Reward, and a Free Pardon. It is supposed the Tree was stolen, for the Purpose of making the Top of a May Pole.

If anyone squealed or ratted out the May Pole makers, I can’t find any account of it.

Of all the handles in the world, “Amabel” was the one MG chose. Why? It’s a name that has about it a kind of pre-Raphaelite refracted medievalism. Amabel conjures days or yore, courtly love, Le Roman de la Rose, chivalric environmens amenable to the flourishing of troubadours, probably named Tristan. Amabel would be the name of the girl who turns up at orchestra camp with her harp. Amabel is a damsel, and probably in distress. She needs to be around sturdy, practical types who can fix things. Like Plummers.

In “New Year’s Eve,” Amabel Bacon is twenty-two. When she was at boarding school and rooming with Catherine Plummer she was Miss Amabel Fisher. Young Mrs. Bacon’s short marriage isn’t working out. She’s going to end things with her husband, who hasn’t given her cause to leave, exactly, but who, when confronted with the possibility of her departure, doesn’t insist that she stay, either. Amabel seeks the twin solaces of the past and elsewhere. She misses her friend, Catherine; mourns her, in fact: Catherine is dead. Needing an escape hatch, anxious for safe harbour over the year’s fraught fag end, Amabel writes to Catherine’s parents. She invites herself to stay with them for ten days at Christmas. This means she’ll have to travel to Moscow. Catherine’s father, Colonel Plummer, is a career diplomat, now assigned to Russia. It was in Italy, his last posting, that Catherine had her fatal collision with meningitis.

The Plummers reply to Amabel, letting her know that if she wants to come she should be aware that they lead lives of dull seclusion, that the climate is dreadful, that she will have to stay at a hotel, vast and brutal, with a tapped phone and on the wall of her room an oil painting of peonies in which in concealed a bug not of the insect variety. To this “perhaps you’d better not bother” ton of bricks the young woman is oblivious. She arrives, and on New Year’s Eve, they go to the opera, not entirely sure what the program will be. It’s there, at the Bolshoi Theatre, for the most part during an intermission of what turns out to be Glinka’s Ivan Susanin - known pre-Soviet era (and now, again) as A Life for the Tsar - that the narrative, in all it’s manifold complexities, unfolds.

“New Year’s Eve” is not a long story, but it’s densely layered. The odd trio at its centre are like Matryoshka dolls, all replete with versions of themselves that are extracted and displayed and examined. In one way or another, they’re all shattered. Amabel’s marriage is in tatters, and she seeks from the parents of her dead friend, from Mrs. Plummer particularly, a comfort and validation - a mothering - that is not forthcoming. Amabel’s timing is not auspicious. The Plummer marriage is on the rocks, held together by the thin mucilage of time and habit. Mrs. Plummer - Frances - blames the Colonel for their daughter’s death. She plans to leave him as soon as she’s scraped together enough money from her afternoon bridge game winnings: she keeps her savings hidden in a dresser drawer. And as for the Colonel, whose gift for languages has been such an asset in the foreign service, well, he is utterly unable to interpret the needs of either his wife or their guest.

To New Year’s Eve - the occasion and the story - Amabel brings a kind of magical thinking. She keeps insisting that what happens on that night will determine the shape and colour of the year to come. (In a diary entry she published in Slate on August 11, 1997, MG makes the same observation, i.e. that the way you spend your birthday - which is, of course, a kind of new year -is both predictive and prescriptive. )

Mrs. Plummer tolerates this naive primitivism publicly, but privately dismisses it as nonsense.

The persistence of memory determines what each day of the year will be like, the Colonel's wife decided. Not what happens on New Year's Eve. This morning I was in Moscow; between the curtains snow was falling. They had no color. It might've been late afternoon. Then the smell of toast came into my room and I was back in my mothers dining room in Victoria, with the gros-point chairs and the framed embroidered grace on the wall. A little girl I had been ordered to play with kicked the baseboard, waiting for us to finish our breakfast. A devilish little boy, Hume something, was on my mind. I was already attracted to devils; I believed in their powers. My mother's incompetence about choosing friends for me shaped my life, because that child, who kicked the baseboard and left marks on the paint…

Here, and all throughout “New Years Eve” are echoes of earlier writing and premonitions of pulses that will beat in stories yet to be born. Amabel remarks with wonder how people in Moscow haul fir trees home for New Year rather than at Christmas, and this reminds me of Carol in “The Other Paris,”taking in the mistletoe hanging from Parisian trees, and Lottie Benz in “Virus X,” arriving in Paris in December, from Winnipeg, and being principally surprised to find that there’s holly in her hotel. As for Mrs. Plummer, scotching the notion that what happens on the ramp-up to midnight on December 31 will influence the year to come, and her remembrance of her Vancouver Island childhood in Victoria, I think of how there is so often in MG’s stories a boy - the visiting cousin, the wrong-side-of-the-tracks neighbour - who’s devilish or who inspires devilry. Here, in Mrs. Plummer’s toast-scented Proustian recall, we see the veil lifted on Jack in “The Moslem Wife;” Jack who owes his lifelong limp - the mark left on his paint - to his cousin Netta’s cruel kick.

Jack’s tragic flaw is his quality of memory, or lack of same. He’s devoted to Netta when they’re in the same room, but she fades from mind and heart as soon as they’re apart. It’s easy for him to wander. Colonel Plummer is likewise inclined to stagger; is prone both to infidelities and to lapses of recall.

The thing he was most afraid of now was losing his memory. Sometimes he came to breakfast wearing two kinds of shoes. He could go five times to a window to see if snow was falling and forget each time why he was standing there. He had thrown three hundred dollars in a wastepaper basket and carefully kept an elastic band. It was of extreme importance that he remember his guest’s name. The name was royal, or imperial, he seemed to recall. Straight down an imperial tree he climbed, counting off leaves: Julia, Octavia, Olivia, Cleopatra – not likely – Messalina, Claudia, Domitia. Antonia? It was a name with two a’s, but with an m and an n.

Aha! The Colonel was sharing of my own first reading confusion about “Amabel / Anabel.” Maybe it’s a guy thing.

Echoes and premonitions. The Plummers and Amabel are tightly packed into a box at the Bolshoi, but they are utterly isolated, one from the other. MG has painted a painful portrait of three lonely people, insulated and isolated. They’re each haunted by ghosts no one else can see or hear. It’s incredibly sad. MG uses a kind of cinematic technique to great effect, panning the group, then focusing in on each of the trio, their particular and private miseries, their separate and desperate trains of thought.

She does this, too, in the stories that comprise her novel that’s not really a novel, Green Water, Green Sky, and in the well and truly novel A Fairly Good Time, also published in 1970. From a purely technical point of view, the way MG manipulates the narrative with such subtlety and force and originality is really an act of something like genius.

Open the windows on “New Years Eve” and all kinds of fragrant, familiar breezes waft in. When Mrs. Plummer remembers the Easter the Colonel went off on one of his romantic adventures and Catherine tore up the pansies she had planted, we remember the moment in “Voices Lost in Snow” when the child Linnet, in the throes of irrational rage, tears up the tulips (and eats them.) Here, as in many other stories, including “The Moslem Wife” and “In Youth Is Pleasure,” MG takes the time to describe the qualities, pleasing or otherwise, of overheard laughter. The Colonel’s mother is still alive, and she’s the one he wants with him at Christmas, despite her fragility, and the choking quality of her laughter. I suspect, speaking of echoes and Colonels, that MG was quite deliberate here in alluding to her cherished avatar Katherine Mansfield’s story “The Daughters of the Late Colonel,” in which the eponymous children wonder about the disposition of their later father’s possessions, including his top hat - should it go to the building porter who had to wear a bowler to the funeral? Amabel has come to Moscow incubating the fantasy that Mrs. Plummer will bestow on her, Amabel, her dead daughter’s possessions. But no. Mrs. Plummer gave away all Catharine’s (not Katharine’s but one wonders if this is another Mansfield embrace) clothes and books and as for the little dog, well, she had it killed. And who got those souvenirs? Not the porter, but the gardener, in Italy; the gardener and his children.

Well. Enough, already. My recommendation is simply, before the year deepens and the days grow longer, to read or re-read “New Year’s Eve.” There’s much from it to be gleaned. Also, here's a link to a really fascinating and intelligent and good-humoured discussion of the story on Texas Public Radio with Yvette Benavides and Peter Orner. (Orner has written a lot about MG, including the introduction to the New York Review of Books edition of the two novels.)

By way of envoi, here’s another Amabel poem — three stanzas, there were many more, but you get the idea — published anonymously (and no wonder!) on Nov 9, 1815 in the Cheltenham Chronicle and Gloucestershire Advertiser. Cheers! Thanks for reading. Prosper and thrive in 2025.

Amabel

Sure there is witch’ry in that eye,

And witchr’y of the darkest dye;

Or could one glance thus break my rest,

And raise this tumult in my breast -

Make all my my vital tide stream flow

With maddening speed, and burning glow?

’Tis witch’ry sure, I feel the spell,

From the dark eyes of Amabel.

Yet, trust me, all the danger lies,

Not in the witchr’y of her eyes -

Majestic as the wife of Jove,

And graceful as the Queen of Love;

Her form too kindles such desires,

Such unextinguishable fires,

My captive senses with her dwell,

And fancy gives me Amabel. …

Ah! did she know and feel my pain,

Compassion for the wounded swain

Would ease the anguish of the dart,

And sooth again to peace my heart.

Beneath the witchr’y of her eye

A willing victim I could die.

I’ll stell, tho fatal be the spell,

Another glance at Amabel.

Thanks for your discursive approach to New Year’s Eve, including AI’s editorial commentary.

This is one of my favourite Mavis Gallant stories. I laugh aloud while reading it and am touched by the human bond mysteries she probes glancingly and deeply. She does weathers and weathering so well.

I am glad you provided the link to Texas radio and the engaging conversation with Yvette Benevides and Peter Orner.