Grief, Memory, Three O'Clock in the Morning: July 10 / 2025

Fanny, Sally, Louise, Jean, Veotta, Barney, and Joe

This is where I write about Mavis Gallant (MG). If you read this you will wonder how on earth any of what follows pertains to MG. If you stick with it, you’ll see.

On Monday, July 8, obedient to I know not what instinct, I did some Wikipedia level skimming about the American writer Fanny Howe. I’d never read her in a deliberate or disciplined way but reliably, on the rare occasions I’d encountered one of her poems (always by chance) I found it affecting, was surprised by it, admired it, was impressed by a kind of courting of danger that seemed to electrify her writing. There had been every good reason to make time for Fanny, but I had not. Why Monday was the day I woke in a mood to find out more about her whys and wherefores and reasons I can’t say.

I was first surprised to learn how wide ranging was her inquiry: stories, novels, essays, young adult fiction in addition to all her collections of poetry; and then I was dismayed that so few of her more than fifty books were available at the public library. (I must ask the interlibrary loan sherlocks to track down her first novels, published pseudonymously as Della Field: California Nurse [Avon, 1963] was followed three years later by Vietnam Nurse.)I borrowed what they had, all poetry, went home, and the next day, preparatory to reading, I googled anew and found out Fannie Howe had died. Just died. Died that very day. It gave me a queer turn. She was eighty-four.

Fanny, I admit, is extraneous to the following story, but also not. I mention her in passing because I found it eerie that this third-tier interest had risen to the fore just at the moment she was dying, and also because on that very same day - there was a lot of death in the air - I thought to look into the condition of Jean Staples Johnson. It is with Jean Staples Johnson that we begin to move towards MG; Jean Staples Johnson who, as I learned, had also recently (though not so recently as Fanny) forsaken her connection with the quick.

Jean Staples Johnson was 102 when she stepped into mystery on June 6, 2024, in Colorado. I may not be alone in having missed this news, which was not widely reported, despite Jean’s impressive longevity and her considerable reputation as a talented and versatile illustrator. As Jean Staples she was the graphic provider for a trilogy of picture books written by Louise Eppenstein: Sally Goes Shopping Alone (1940), Sally Goes Traveling Alone (1947), and Sally Goes to the Circus Alone (1953). The titles speak to the theme: Sally was a pint-sized exempla of self-sufficiency. It was probably a wise decision on the part of the publisher not to pursue the franchise to the inevitable coda, Sally Dies Alone.

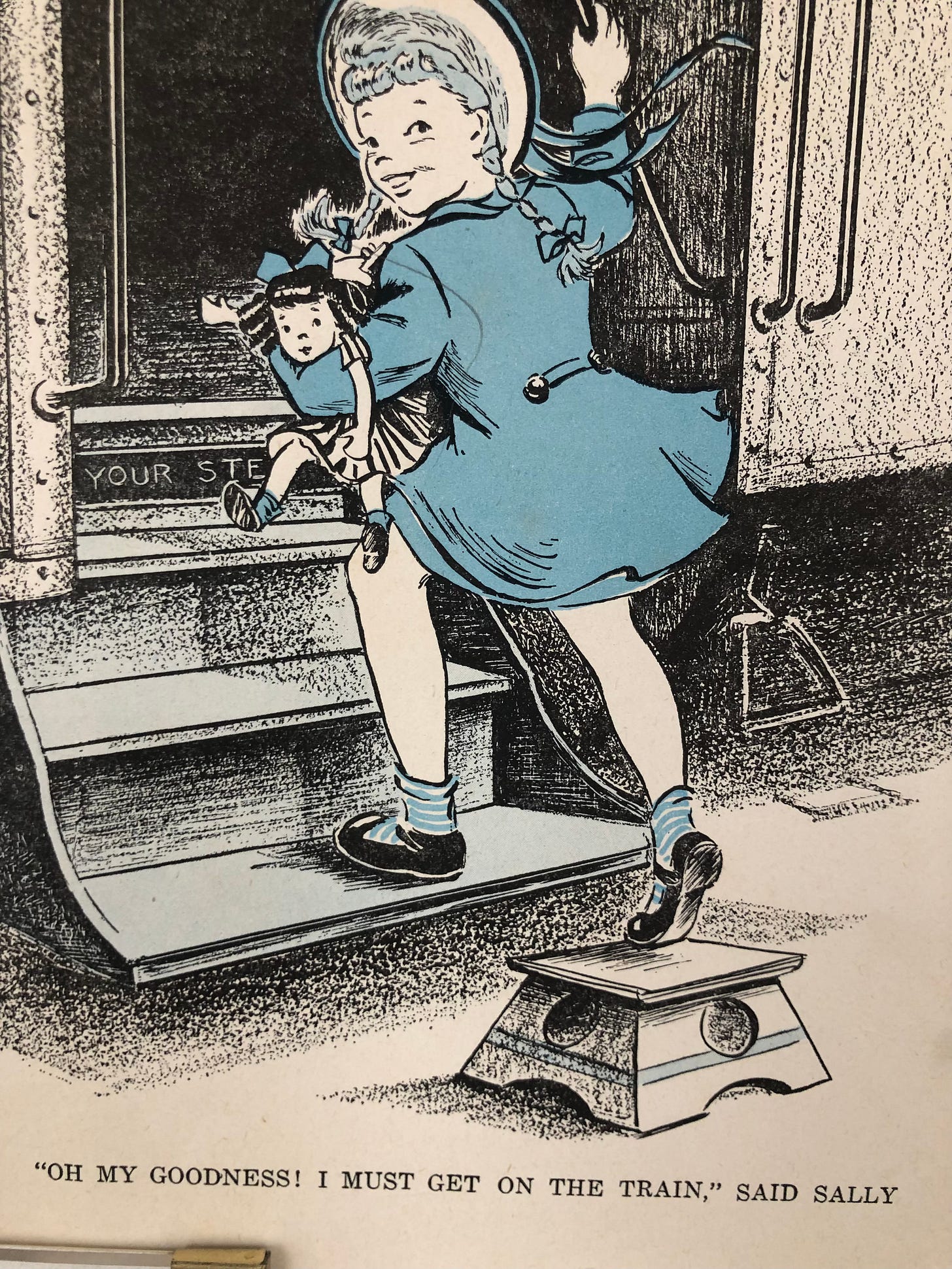

Sally Goes Traveling Alone figures prominently, maybe even disgracefully, in my decor. A while back, in what may have been a liquor-fuelled spasm of late-night artsy-craftsyness, I razored the illustrated pages out of a copy I’d been given (very thoughtfully, as a gift, forgive me, Herb) and attached them with fridge magnets to the exposed end of a narrow metal bookcase adjacent to my little monk bed. There they hang, a poor man’s fresco, Jean Staples’ interpretation of Sally’s journey and various minor mishaps always put to right by the helpful porters and waiters. That they are all Black provokes, of course, a contemporary cringe; but Jean’s intentions were merely documentary, and that would have been any old passenger rail car in America in 1947.

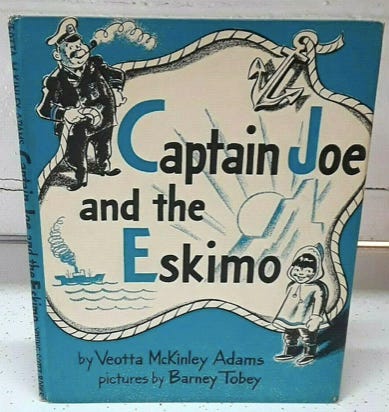

I like the modest palette chosen by Jean, the way the blue predominates. I haven’t read enough about the history of children’s book illustration to know if this was generally reflective of a post-war practice, but I was struck by an aesthetic echo to a 1943 picture book called Captain Joe and the Eskimo.

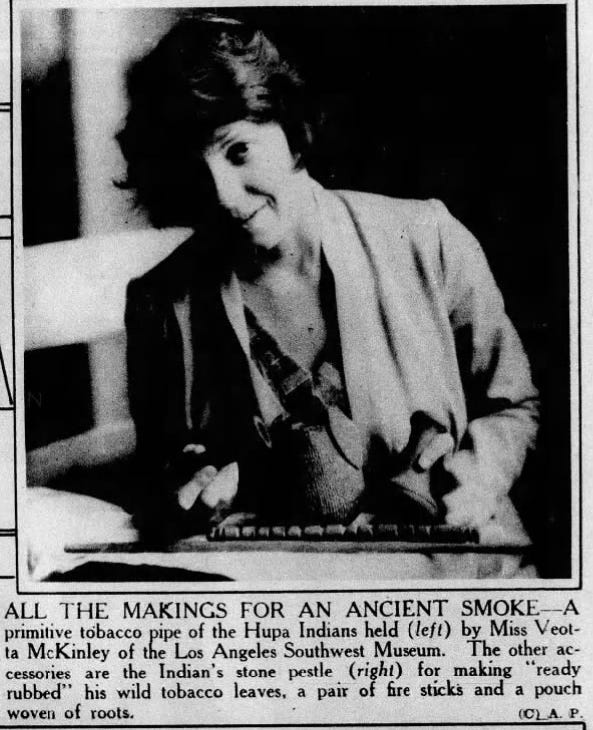

This was the work of Veotta McKinley Adams, 1907 - 1990; the illustrations, also blue and black and white, were by Barney Tobey, 1906 - 1989. Veotta is her own fascinating story. She started out in Oklahoma, then gravitated to California. She was just twenty and a freshman at UCLA when she sold four children’s stories to a Kansas City publisher; if they ever appeared, I find no record of them.

By 1929, Veotta’s interests had taken an anthropological turn. She found work (presumably part-time, as a student) as a “curatorial assistant” at the Southwest Museum. For a year or so, she seems to have been a great favourite of photographers for the LA Times who were forever swinging by and snapping pics of pretty young Veotta showing off indigenous art work, either holding it up for inspection or, if wearable, modelling it. She made her Times debut (above) as the museum spokesmodel September 12, 1929, beaming from a feature photo that accompanies an article about how Charles Amsden and M. R. Harrington, on the museum’s behalf, “spent several days ransacking the pueblos of Santa Fe, Santa Domingo, Cochiti, Tesuque, Santa Ana, and Sia and brought back a large collection of Indian pottery…”

“Ransacking.” That is what is written.

Here’s a little album of Veotta at work. (The “Sioux papoose” noted in the first caption was Zintka Lanuni whose story is remarkable and heartbreaking.)

How long the association with the museum lasted I can’t tell you. Veotta became a teacher, married a flight surgeon, raised a couple of boys and at some point travelled to Alaska where she found inspiration for Captain Joe and the Eskimo. Here I lift wholesale the Google Books synopsis.

Captain Joe sailed his steamship into the far north Arctic Sea. All he saw was ice, and more ice, but one day he saw a little Eskimo boy sitting on a piece of ice. The Captain called and asked if the boy would like to be rescued and the little boy called back and said yes. Captain Joe asked if the boy could climb, and threw over a rope. But the boy only knew how to climb ice, not ropes, so his climbing knife cut the rope to bits. Then the Captain threw a life preserver overboard, but instead of grabbing the preserver and being hauled up to the boat, the boy cut it loose and used it for a little boat. After the Captain threw a barrel to the boy (he carved a nice paddle from part of it) and a lard bucket to climb into (the boy found the leftover lard delicious) the little Eskimo boy was very grateful because now he had enough equipment to paddle home on his own.

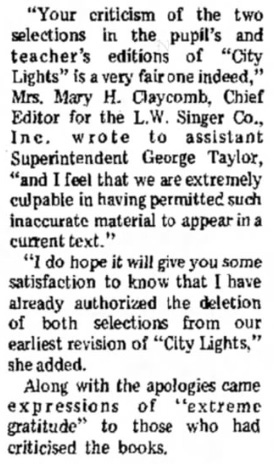

It’s actually quite a charming little story in its way. Like Sally Goes Traveling Alone, it was very much of its time, utterly well-meant, innocent in its intentions even if retrospectively maladroit in execution. There’s no need for me to enumerate the reasons it would not do now. Captain Joe was well received at the time of its publication, had positive reviews, enjoyed a happy life for a season or two, and then more or less faded from view until 1969, by which time hearts and minds were beginning to shift in the direction of our present position. In 1969, Captain Joe and the Eskimo was resurrected from God knows where and published as part of a supplementary curriculum circulated among teachers in Alaska. Properly, they bristled and complained to the publisher, L W Singer, an educational subsidiary of Random House. The editor, Mrs. Mary H. Claycomb, listened attentively and apologized profusely. She understood exactly what the problem was and the material was withdrawn.

I have no idea who Mr. Claycomb might have been (and I’ve tried to find out, believe me), nor can I say when Mary met and married him. I only know, via an appreciation of Mary Harnett Claycomb written by a friend after her death in 2020, that it was an unfortunate and short-lived alliance about which she never spoke. Mr. Claycomb, I think we can safely suppose, was cut from the photos with the same alacrity I applied to the illustrations in my gifted copy of Sally Goes Traveling Alone.

Four years earlier, in 1964, the future Mrs. Claycomb was living in Chicago and still going by her maiden name, Mary Meade Harnett. I know this because of the inscription on the flyleaf of her first edition copy of MG’s My Heart is Broken, which I now own. That book that was Mary’s and is now mine lives in the bookcase decorated, as pictured above, with the illustrations from Sally Goes Traveling Alone; the blue and black and white illustrations that are so reminiscent of Captain Joe and the Eskimo that got Mary Harnett Claycomb in such hot water a few years later. Her collaborator, the illustrator Barney Tobey, achieved his widest fame as a New Yorker cartoonist and very often he and MG shared space between the covers. As it were. If you know what I mean. You should forgive the expression.

A lot of words for not much, and that’s all there is to it. Like I said - all roads lead to Mavis if you only follow them long enough.

P.S. No more than fifteen minutes ago, the mail arrived at my door. The letter carrier knocked to let me know there was a package that wouldn’t fit through the slot. It was the latest Paris Review, Number 252. I keep my Paris Reviews in that self-same bookshelf. This new one includes - the weirdness continues - an interview with, who else? - Fanny Howe, may she rest in peace, may her memory be a blessing. To Fanny I will now direct my attention, and I thank you as always for reading. BR

A tour down a lazy river, but not by a lazy commentator, wherein we eventually find ourselves in the Sea of MG. I did a little sleuthing of my own. Seems Mary Meade Harnett Claycomb may have been married to a Robert Claycomb in 1964. She established a publishing company called Claycomb Press in 1985 which published a variety of books, many YA. Would she have used the Claycomb name for her publishing company had they separated and divorced?

One of her authors was Everard Meade, some kind of familial connection between publisher and author - through the very prominent Virginia Meades, whose ancestors include other Everards. The Meade family has been traced back to 15th century England.

The wondrous serendipity that comes with what may appear to some to be idle, online rabbit-hole burrowing should never be discounted. Six-degrees-of-separation discoveries are always lurking there and they're often unearthed in the most unexpected places. Bill, this lovely meandering account of your tapping and scrolling proves the point perfectly. Your time was well spent. You may enjoy the blog post by Rebecca Foster on instances of "book serendipity" of a somewhat different kind that mirror some of what you have chronicled. And, serendipitously, wouldn't you know it? Fanny Howe comes in for mention: https://bookishbeck.com/2023/12/21/book-serendipity-october-to-december-2023/. Rebecca Foster's blog is always a delight. It will not surprise you that when she was prompting her readers a few years ago for ideas about short stories to read, an exchange with someone urging her to read MG resulted: https://bookishbeck.com/2018/09/28/short-story-collections-read-recently/ Ah, serendipity! Tom aka PWB.