I’m happy that Montreal Standard Time, the selection of Mavis Gallant’s early journalism, written for the Montreal Standard between August of 1944 and October of 1950, has been published by Véhicule Press. I’ve been jeopardizing the future of my embouchure, and probably testing your patience, by trumpeting its advent over my last several missives; I hope that anyone who’s interested in seeing at work the big young brain of one of our most exciting writers will seek it out. Likewise, I hope that, in addition to the wide-ranging writing of Madame Gallant, the sine qua non of the enterprise, you’ll enjoy the contributions (they’re brilliant) made by my co-editors Neil Besner and Marta Dvorak.

My job was to write the annotations that appear by way of an appendix towards the end of the book and, as previously noted, I gathered up much, much, much more information than could be accommodated — or should have been accommodated — in those pages. A few people let me know they appreciated seeing the unabridged texts I published last time round, and for those with the time or patience or interest to read more deeply about the background of some of her features, I’m going to append, over the next few days, the full meal deal. No one would hurry to call this “necessary reading,” but the fan girls and boys out there might find something here of interest. Of course, none of these make much sense abstracted from the writing they describe and THAT you can find in the book, available soon (possibly now) in bookstores, or from Véhicule Press here.

Thanks as always.

Meet Johnny

The Montreal Standard was a weekly. It published on Saturdays. In June, 1944, when Mavis Gallant (MG) began her six year stint there as a staff writer, it cost ten cents. Readers got a lot for their dime. First came the rotogravure, or roto: the photo-based stories. Every week, there were three or four of these, many concerning the war. Next were the features, usually a couple of thoughtful, well-reported articles on contemporary issues, again, often war related. The features were followed by a generous selection of fiction, more popular than literary, several original short stories, and a condensed novel from a syndication service. Then came the comic strips, including Terry and the Pirates, Jane Arden, L’il Abner, King of the Royal Mounted, Popeye, Tarzan, Prince Valiant. Finally, there was a wrap-up of the week’s news, along with some recipes and domestic advice from the redoubtable Kate Aitken who was, with the possible exception of Barbara Ann Scott, then the most famous woman in Canada. It was an ambitious production, week after week, often in excess of a hundred pages.

A frustration that appends to writing about what MG called her “apprenticeship” — she joined the Standard staff in June, 1944 and left in September, 1950 — is that paper and paste copies of The Montreal Standard are pretty much impossible to come by. Occasional examples (none in tip top shape) can be found online via second hand booksellers, but at prohibitive prices that reflect their rarity. ($300.00 U.S.would be the range, long gone the day of the dime.)

A text is a text is a text, and the means of its conveyance doesn’t alter its meaning. That said, ambience counts for something and spooling through reels of grainy microfilm, and then, later, at home, squinting at smudgy photocopies of those often distorted, age-spotted images — some as impenetrable as Cuneiform — is an experience less ideal than would have been reading this strong-minded young woman’s early (and already accomplished) writing in its natural and intended setting: a lively tabloid densely packed with photographs, features, fiction, comic strips, and ads. The Standard was designed to be eye-catching, vibrant, with pages that popped. Its stewards never had in mind the black and white experience, which, alas, is now all that remains to us, barring the discovery of some cache that wouldn’t eat up all the cash. One can only wish.

If wishes were horses, I’d conjure up one that could travel over time as well as space, and canter back to September 2, 1944, to Montreal. I’d don my cloak of invisibility — it would be there, in the saddlebag, part of the package from Wish Brothers Rent-a-Steed — and watch MG — two weeks into being twenty-two, two months into her six year tenure at the last salaried job she would ever hold — open the paper that contained her first-ever professional byline. On the cover, imposed on a graphic of some hornpipe dancing sailors, was a photograph of the grinning able seaman Enio Girardo, born in New Westminster, British Columbia, who had a season of unexpected celebrity when the story of how he was plucked from the North Atlantic after being washed overboard caught the wartime public’s good news-starved imagination. (When Enio died, in 1971, no mention was made in his obituary of his dramatic rescue, nor of his brief career as a cover boy.)

Of course, MG would have known exactly where in the opening pages, in the roto, she would find that milestone marker, her name in print, the first public acknowledgement, the irrefutable proof that she had become what she always knew she would be, a writer. But what was her tactic of approach? Did she go straight away to the page where her flag was planted? Or did she savour the moment, begin at the beginning, turn the pages slowly, reading legendary Earl Lawrence’s gripping reporting on the Allied march through France, and sports writer Andy O’Brien’s light-hearted piece about finding himself a punching bag for WACs learning martial arts? She was close now, she was very close. Did she delay gratification, carefully absorbing the information in the piece that preceded her own, an earnest description of how rubber can be made from dandelions?

“Don’t you dare say I cried,” MG told a reporter, late in her long life, describing an emotional family moment from the time of her youth. I won’t dare to say so here — how would I know? — but surely an emotional surge took her over when she came to her destination, to the brief span of pages, 12 to 15, and saw, as readers across the city (and across the country, for the Standard had a national circulation) were seeing her 700 words and the 19 photographs taken by Hugh (Hy) Frankel. It was, it must have been, at least as powerful, as unforgettable, as a first kiss. For the rest of her life, she would remember “Meet Johnny.”

Radio Finds Its Voice

The radio is a regular if minor pulse point throughout MG’s writing. In the Selected Stories, there are forty-three references — some passing, some more consequential — to radios playing in private rooms or public places. In her fascinating, quite daring play from 1982, What Is To Be Done? —it reads like a gleeful amalgam, The Golden Notebook meets Waiting for Godot meets Paddy Chayefsky — the radio, urgent conveyor of news from the front, is a steady, absurd, presence. In “The Events in May,” her brilliant diary record of the Paris student uprisings in 1968, the radio, the BBC most often, is a late night or early morning companion, sometimes reassuring in its confidences, sometimes alarming. She begins her essay on the critic and diarist Paul Léautaud with a story about her discovery of French radio upon arriving in Paris in the fall of 1950. To radio, MG paid attention. It was a part of the quotidian of which she took note which, in part, was a generational trait.

MG’s birth in 1922 was coincident with the dawn of commercial broadcasting in Canada. The new stations’ voracious appetites needed daily feeding. Radio became a gathering ground, particularly after the founding of the CBC in 1936, for some of the brightest and most ambitious of the country’s young creative minds. The medium itself was newsworthy; by 1944, there wasn’t a major daily in North America where it wasn’t an assigned beat. The Standard (a weekly) was late to the game in this regard — MG began her stint as a radio reviewer, with the column “On the Air,” in 1947 — but her interest in radio and its makers is evident in “Radio Finds Its Voice,” her first foray into full-length reporting for the features or “magazine” section of the paper.

Time bore out MG’s intuition — her excitement is palpable — that here was something not only new but notable, game-changing. The “Stage” series would run for twelve seasons, a total of 408 shows: half-hour plays through 1948, then hour-long dramas. If MG, still a rookie, had to work hard to persuade her editors that these innovative Sunday night broadcasts could withstand the weight of 1800 words of analysis, Jack Gould handed her a trump card. Then, as now, nothing stirs a Canadian heart so much as approbation from abroad, and on November 19, 1944, The New York Times published Gould’s paean, “Canada Show Us How.”

“Tossing aside radio’s conventional taboos for the utter nonsense they are, they delivered a resounding blow to the homegrown variety of fascism by a magnificent blend of humor and understated anger that was radio at its most exciting. … Mr. Sinclair and the CBC have shown that radio can awake and sing as well as other media. . . . [The] CBC gave its listeners credit for being mature enough to accept a stiff dose of reality along with fine entertainment. Radio was grown up last Sunday in Canada.”

The wave-maker was “A Play on Words,” and Mr. Sinclair is Lister Sinclair (1921 - 2006) who, at the time, was a lecturer in mathematics at the University of Toronto. Famously erudite, he remained at the CBC in a variety of guises — including a stint as a program director — until 1999. He is probably best remembered as the host (1983 - 1999) of the long-running radio programme “Ideas.” The other names cited by MG in “Radio Finds Its Voice,” constitute a kind of Who’s Who of the Golden Age of Radio Drama (as that period of production is often called) at the CBC. The most notable include Harry Boyle (1915 - 2005), who was twice a winner of the Stephen Leacock medal for humour, and served a term as Chair of the CRTC. Len Peterson (1917 - 2008) was a hugely prolific writer of stage, radio, and television plays. An activist involved in the formation of ACTRA and the Playwright’s Union, his plays were known to stir Parliamentarians to demand closer supervision of the CBC, or for its defunding. Bernard Braden (1916 - 1993), often in partnership with his wife, Barbara Kelly, became a staple of BBC variety broadcasts in London. He was part of a West Coast cohort that included Fletcher Markle (1921 - 1991) who was producing radio dramas in Vancouver as a teenager, and went on to have a substantial and lengthy career in the U.S. and in Canada as a writer, director, producer and presenter in television and film. In his capacity as host of CBC Television’s “Telescope,” he interviewed MG in her Paris apartment for a two-part episode broadcast in 1965. It was her first extended Canadian interview. Alice Nora Frick (1914- ?) also parlayed her time at CBC into a job in drama production at the BBC. She wrote a book, Image in the Mind: CBC Radio Drama, 1944 - 1954, which is a full account of the “Stage” series. She worked closely with Andrew Allan (1907 - 1974), with whom MG would have felt a kinship, given that they shared their August 11 birthday. Allan’s experience was unfortunately usual in that he left radio for television which proved to be a medium for which he was not evolved. He was the Artistic Director of the Shaw Festival from 1963 - 68. His eventful life is described in his memoir, Andrew Allan: A Self-Portrait.

Stalag Diary / Report on a Repat

In 1946, Flt. Lt. Bruce Dawson Campbell (1913 - 2008), newly returned from the war, newly married, and a first year student at McGill, published Where the High Winds Blow. (Her husband, John Gallant, also newly demobbed, was also a first year student at McGill, which was perhaps the connection.) Not to be confused with David Walker’s 1960 novel of the same name, Where the High Winds Blow came out in the U. S. with Scribner, and in Canada with S. J. Reginald Saunders and then, in 1951, with The Book Society of Canada. It’s an account of Campbell’s years, 1934 - 1937, as a fur trader with the Hudson’s Bay Company “in some of the loneliest outposts of that organization in the Eastern Arctic,” as the publisher wrote. Long out of print, it was a bestseller, a Book of the Month Club selection, and was, for a few years, on the Ontario tenth grade curriculum. Though outmoded in all the ways you might expect — racial stance and diction, though his admiration for his Inuit hosts and colleagues is clearly and genuinely expressed — the book remains an engaging read. In addition to the story’s intrinsic worth, readers were captivated by the story of its composition. This is from the Publishers’ Note:

“… he was a prisoner of war at camps in Poland, on the Baltic, in Bavaria, and last of all, Stalag Luft III, at Sagan in eastern Germany, where he spent nearly two years. Here he had given perhaps seventy-five talks on his Arctic experiences when someone suggested to him he should write a book. He had the good fortune to find a collaborator in Philip Bear, an English artist who had spent two summer aboard a whaler in polar waters. Writer and illustrator had mechanical difficulties to surmount: special permission to use ink and paper was necessary; papers, pencils, and paints had to be obtained through the International Red Cross and the Y.M.C.A. The two did their work in the midst of twelve other men in a small room. Bruce Campbell rewrote his manuscript three times and carried it on his person during a forced march through Europe…”

It’s curious that no mention is made in MG’s writing for the Standard of the manuscript that became Where the High Winds Blow — the writing of it was obviously a focus of Campbell’s days as a POW, and as its publication was less than a year away, it couldn’t have been a deal still in the works — and the only mention of the 75 lectures that formed the body of the book comes in a caption to an illustration of a camp poster that seems to have advertised one his talks about the Arctic. That said, the war diary she describes is a remarkable document and, as near as I can tell, this is the one account of its assembly.

On November 7, 1964, an article by Bill Trent, with photos by Louis Jacques, appeared in Weekend Magazine (as the Standard became in 1951) called “Mama Maria’s Lost Airman.” It told of a reunion between Bruce Campbell and Maria Rutten-Geurts, the Belgian woman who briefly gave him shelter after his plane was shot down. Where the High Wind Blows was his only book. He worked as an insurance underwriter, was a founding member of the Pointe Claire Lawn Bowling Association, and was 95 when he died in 2008. His wife, Helen Gilmour Campbell, died in 2009, age 93. His wartime diary, according to his surviving daughter, Tracy Pike, remains in family hands.

————————

How did MG settled on Roland Langlois as a subject? Presumably, looking to tell the story of an ordinary enlisted man, she was connected to Langlois and his family through an army public relations officer. His father, Théodule, with whom he was photographed, had been pictured, with three others, in The Montreal Gazette, on January 3, 1939, as part of an article having to do with the history of road building in Montreal; that had been the elder Langlois’ work. It was entitled “Oldsters Describe Early Days in City.” He was said to be 74 years old.

Extensive lists of combatants missing, imprisoned, killed, or returned appeared in the daily papers. Roland enlisted as a Private with Les Fusiliers de Mont Royal. On September 6, 1942, he was listed in the Gazette among those injured at Dieppe. On December 30, he appeared among the list of those taken as POW’s. April 30, 1945, in the Gazette, he was listed as one of fifty-two newly-liberated POW’s. His address was given as 5203 St. Dominique Street.

On July 29, 1950, MG published in the Standard a followup piece, one of her last assignments, on the fifth anniversary of his repatriation. Langlois and Eugenie were still married. They had a second child, Richard; he was three at the time. Claudette was by then eight. Langlois had become a tram conductor. He had lost 36 pounds, weighing in at a svelte 133 pounds. They still lived with Eugenie’s family, and seemed happy to do so. Both his parents, MG reported, had died.

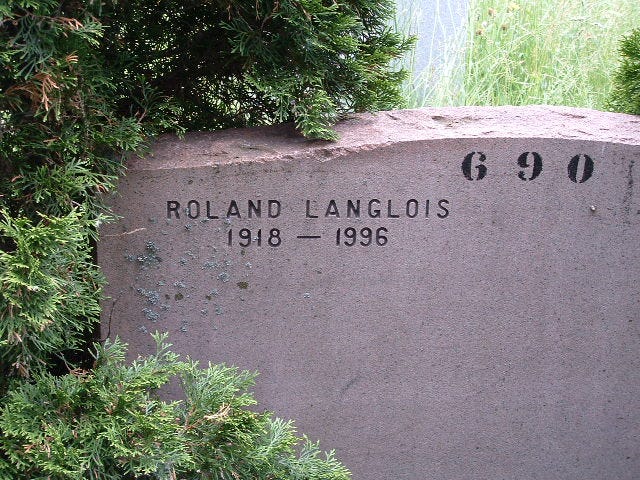

After that, the Langlois family seems to have lived quietly, keeping a profile low enough to insulate them from the news. Eugenie died on July 6, 1966. In her obituary, a third child, Sylvie, is mentioned. Roland, born February 23, 1918, died January 14, 1996. He was buried in the Notre-Dame-Des-Neiges Cemetery, Montreal.

While Langlois was not forthcoming about his time as a POW, a sense of his daily life, while interned, can be had by reading the “Memory Project” account of Armand Emond, who was captured with him. (This is accessed via The Canadian Encyclopedia.)

“So we spent 32 months in Poland and 14 months in handcuffs! We worked from 8 in the morning until 6 at night. We worked in the woods, you may have seen photos, and then in the summer during the harvest, we would start working at 6 in the morning and work until 6 at night, since the soldier, he told us: “Any prisoners who refuse to work will be shot!” So we worked 12 hours per day and then the autumn grain and potato harvest began (in the fields), and we began working a bit later. We worked 6 days a week. Between us, as prisoners, the relationships were very solid. We were like brothers.”

Duncan and MacLennan, Writers / Maria Chapdelaine

MG — city-bred, an urban sophisticate — also liked to get out of town. She was as happy in Chateauguay as she was in Montreal, as at home in Menton as she was in Paris. Largely self-assigning, she made it a point while at the Standard to cover stories that would take her to outer city boroughs, or to more distant, even remote, part of the province — Sorel, Abitibi, Ste. Adele. Also, she liked a literary pilgrimage. The crew filming her 1965 Telescope interview with Fletcher Markle followed her to the Proust museum in Illiers-Combray (a favourite day trip), and in her short fiction characters visit the gravesites of Katherine Mansfield, Chateaubriand, and assorted tubercular English poets, gone to dust in Italy.

In “Maria Chapdelaine” and “Duncan and MacLennan, Writers,” photo-stories from 1945, these twin impulses — visit the country, pay homage to writers — are in play. It’s curious that MG’s story about Dorothy Duncan (1903 - 1957) and Hugh MacLennan (1907 - 1990) appeared on June 9, 1945, three days before this notice appeared in The Montreal Star: “Mr. Hugh MacLennan, Canadian novelist, and Mrs. MacLennan, known in the literary world as Dorothy Duncan, are leaving on Thursday for North Hatley, Que., where they will occupy their country home ‘Stone Hedge’ for the summer.” Plainly, contrary to the implication of that society note, they had already traveled to their country retreat and opened up the house — perhaps they did so for the express benefit of MG and the photographer, Hugh Frankel.

Duncan and MacLennan were older than MG by just enough, and sufficiently advanced in their careers, that they must have been emblematic of a certain vocational and domestic possibility. Dorothy Duncan won the 1944 Governor General’s Award — the presentation took place on November 30, 1945 — for Partner in Three Worlds. In those early days of the award, there was no cash prize, no French language laureates, and two awards were disbursed for nonfiction: one for an academic book, one for popular or “creative” nonfiction. Hugh MacLennan won the first of his five GG’s (3 for fiction, 2 for non) the next year for Two Solitudes. The last of his handful would come for his 1957 novel, The Watch That Ends the Night, inspired in large measure by his marriage to Duncan, and her long illness.

About MacLennan, an important figure in 20th-century Canadian letters, much has been written. Dorothy Duncan, who gave up writing on the advice of her doctors in 1949, and turned, successfully, to painting, is largely forgotten, her books long out of print. This is usual, but also too bad. She was a very assured writer, with surprising insights. MG might have been aware of the excerpts from her diaries (1953) that were published in 2002 in the small details of LIFE: twenty diaries by women in Canada, 1830 - 1996, edited by Kathryn Carter for the University of Toronto Press. Her devotion to her husband and marriage is clear, as is her frustration. “Thursday, March 20. Hugh’s 46th birthday. I’m so accustomed to his remarkable character that I sometimes forget to think about it — until another man behaves like most other men, and then the contrast shows up as acute. I suppose that’s why it hurts me when he uses the term ‘women’ as a curse — for if I am not thoroughly a woman, of what use am I to him?”

Louis Hémon’s Maria Chapdelaine, surely the most successful Canadian novel ever written by a non-Canadian, was an enduring publishing phenomenon by the time MG took it on in 1945. Nearly coincident with her own advent was its rendering into English in 1921; part of the novel’s complicated publishing history is the simultaneous and competing translations that appeared in that year. Its success was immediate, astonishing really, and it went on to sell millions of copies in many languages and editions, as well as being adapted into a hit film starring Jean Gabin. (There have been four film version all told, the most recent in 2021). It spawned a tourist phenomenon as well, drawing many visitors to the village of Péribonka.

MG made her winter trip there — today, it’s a six hour journey north from Montreal, in 1945 it must have been longer — with photographer Henri Paul (1891 - 1974). Like Hémon, he was born in France; his name starts cropping up in Montreal just after the start of the war. He was not closely allied with the Standard, but won his reputation with commercial shoots and with portraits, especially of artists, most notably the performers of Le Théâtre du Nouveau Monde. By this time — given the publication date of January 13, 1945, they presumably traveled north late in 1944 — the Aluminum Company of Canada, ALCAN, was beginning to build its massive smelter-powering hydro electric projects along the adjoining waterways, flooding farmlands, changing the countryside Hémon would have known and portrayed thirty years prior.

It’s striking that the evocative and tightly-written descriptions of the village, the landscape, and the people are the work of a 22-year old journalistic novice. She must have had a sense of urgency about telling the story, about hearing it from sources who didn’t have much time left. Eva Bouchard, who had done well by her claims that she was the Maria prototype, died on Christmas day, 1949. Samuel Bedard died April 17, 1955. In 2020, his house was moved into town to be more proximate the Hémon museum. A hundred and ten years after its writing, Péribonka still owes whatever it can claim of fame to Maria Chapdelaine.

Hugh MacLennan at 46. It always strikes me when someone I considered old turns out to be so much younger than I am now. (I first noticed this when, after my mother passed, I read an essay she'd written for school, age sixteen. That's part of the interest in reading about the young MG, too. Prose, like aspic, preserves young minds.

As a fan girl, I am really keen to read your unedited version of "A Wonderful Country". I wonder how many others she met in that job provided inspiration for the characters in her stories.