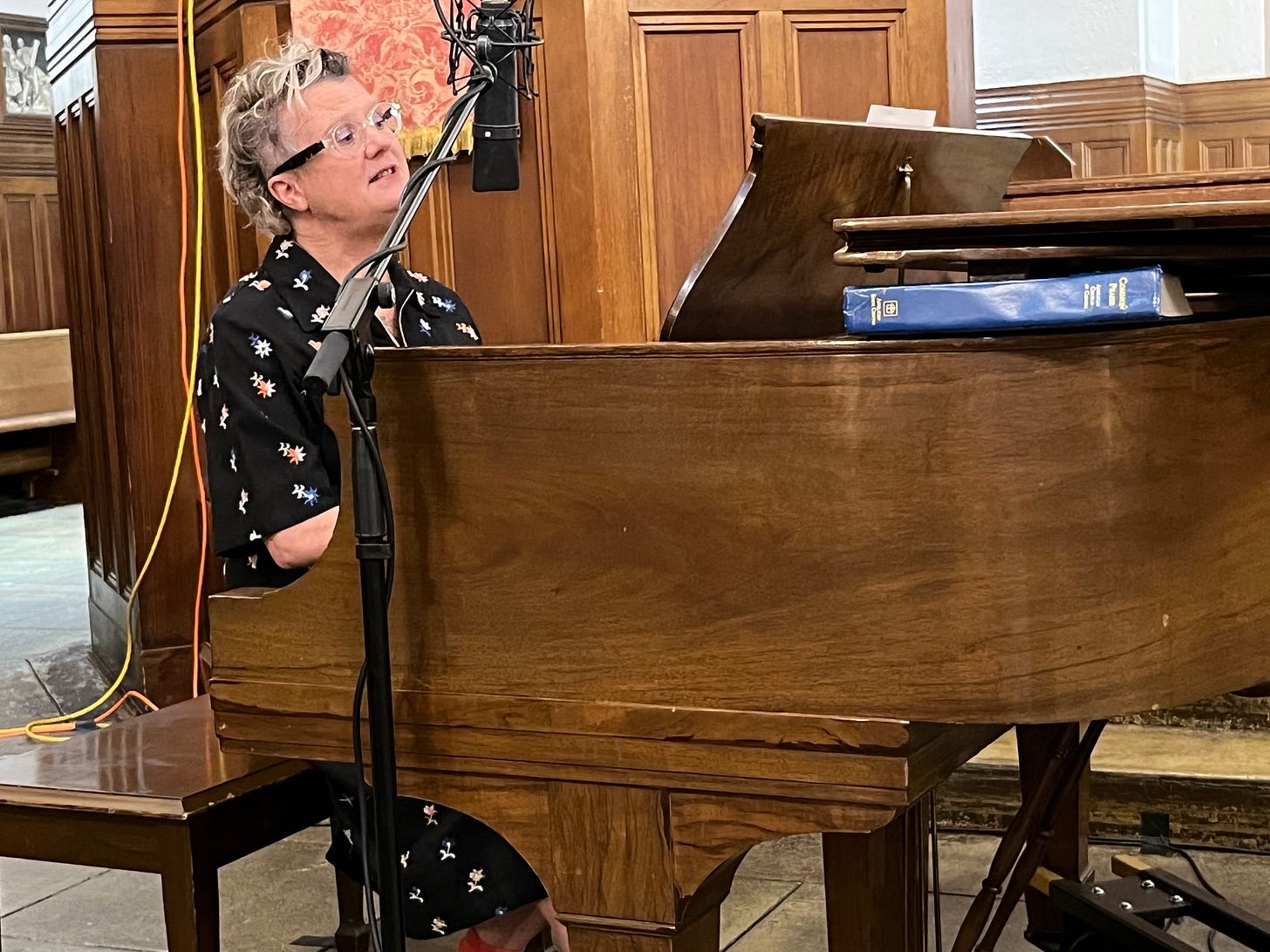

A Compline Service in Honour of Mavis Gallant, born Montreal, August 11, 1922. Recorded August 10, 2022, at St. James’ Anglican Church, Vancouver. The officiant was the Venerable Father Kevin Hunt, Rector of St. James’, Archdeacon of Burrard. Organist, P. J. Janson. From the St. James’ choir, Trevor Mangion and Lyle Isbister. With the distinguished participation of Veda Hille, composer / singer / piano; Gabrielle Rose, reader; and Shefa Siegel, cantor. Recording engineer, Grant Rowledge.

August 11, 2022 / Vancouver, B.C. / 1.31 p.m.

Dear Mavis Gallant (MG):

Here it is at last, your big day. 100 years since you traded gills for lungs, sucked your first air — the insult of oxygen, corrosive on the lungs — and released it as a wail. A century since you were made incarnate, subject to the necessities, indignities, and pleasures of the flesh. Were I to write, “I am thinking about your body,” I’d sound like an intimate companion — not so — or else some creepy nuisance caller, breathing down the line from a pay phone: likewise, not the case; not yet, anyway. There’s no decorous way to say what happens to be so: I’m thinking about your body, and have been since last night when I sat in the front pew of St. James’ Anglican Church, a couple of hours before the compline service we held in your honour was to begin — before the soloists turned up for their sound checks, before the congregation arrived — and wrote out my thank you cards. This is something I almost never do anymore, write by hand; I’ve never been feted for my penmanship, not even when pen and paper were routine, but at least I could lay claim, most days, to legibility. The words of gratitude I laid down those cards had the unmistakeable look of being the work of a child or someone who was very old: motor skills either undeveloped or atrophied.

I have in my keeping a postcard you wrote in the late 1990’s, and I’ve seen enough examples of your handwriting to know that yours was a very distinguished hand, that it remained so until late in your life, a pleasure to read. Not so mine, and oh, the labour of it. A few well-intentioned words on a few blank cards and I was grumpy and cramped and out of sorts. I thought of your body because I marvelled at the idea of you writing, by hand, page after page after page: the first drafts of those 120 stories that you would later type up, to say nothing of all your letters, your diaries, all the stuff of the day to day. I remember you writing about Colette, about her hand, arthritic, permanently seized up in a pen-grip, and I remember a friend of yours telling me that towards the end of your life, when your accustomed acuity would no longer come to a whistle, you would sit at your table and make the motions of writing, for long stretches of time.

Dear MG, speaking of friends, if you’d been reading my diary you’d know — I’ve yammered on it about at length — that I’ve been intrigued by what I took to be your gift for friendship; your genius, really. You were deliberate about cultivating and maintaining that network; I suspect you didn’t over-think it, that it came to you naturally, as all gifts do. You were loyal; you inspired loyalty. When I spoke to Neil Besner — you knew him, you were the subject of his PhD dissertation, the first of what are now many written about you — he talked about how you wrote to him to say that you were peeved that he was digging around, asking impertinent questions of acquaintances, trying to find things out. You’ll be happy to know — so I suspect — that when I began this project, a few months back, I put together a list of people, some you’d known for many years, some for not as long; primary sources I could contact with questions of biography or context that needed settling. A few were glad to talk — no one said anything outrageous or indiscreet — and a few have become my friends, too. But, pour la plupart, my inquiries were met with silence, went unacknowledged. For this there could be many reasons but my best guess is that the main one is discretion and loyalty. “Mavis wouldn’t like that,” they might have thought, knowing how you valued your privacy.

Here’s something a bit strange. Just now, just this very second, today’s mail came through the letter slot: one item only, the August 8 The New Yorker. Now, I would have thought the magazine in which you published the vast majority of your work — 116 stories — and where you were a mainstay for over forty years, might have made a bit of a fuss about your centennial. This would be where that would happen, in the issue covering the week-long span during which your birthday falls. But no. Nothing. Rien. Not a word. Nor is there anything online, not that I can determine.

The feature article — I guess it will come out in print in the August 15 issue — is about Josephine Baker, about her espionage activities during the Second World War. MG, I ask you, would it have hurt them to note, in this, your centennial year, that you mention Josephine Baker twice in your stories — twice that I know of: in “Let it Pass,” and in “In Plain Sight.” Both were written after Baker’s death in 1975. I wonder if it was Josephine you were thinking about in 1968 when you wrote “April Fish.” Josephine was possessed of that mania that seems to attach to some women of wealth and influence — Angelina Jolie, Mia Farrow — for gathering up orphans, for suffering the little children to come unto them. Josephine had 12, and their outcomes were, in many cases, far from brilliant. The woman in “April Fish” is named April; she was born on April 1: it is, in fact, a birthday story, as was the first you ever published in the magazine, “Madeline’s Birthday.” April has three adopted sons, but she wants a daughter, and she wants especially a Vietnamese girl to join her family. She’s upset that this can’t be arranged, simply can’t understand why not. It’s a mordant, funny story, kind of shocking, really. (Wasn’t there an episode of Absolutely Fabulous, a couple of decades later, where Edina was trying to cultivate social currency by adopting a Romanian orphan? I think so.)

Dear MG, this is the kind of fruitless, often stupid speculation I’ve indulged in these last four months. It’s done now. This is the last time I’ll write about you; here, at least. I am thinking about your body, about how, without it, without the hard physical labour you undertook — and it IS hard, writing, it’s manually taxing, it’s hell on the lumbar, it’s exhausting, or can be — none of that legacy of stories would exist.

I am thinking about how you told Neil Besner — and others — that if they dared to suggest in their analyses of your work that there were traces of autobiography you would have your lawyers send a scary letter. But of course, your stories came from you, from your mind, via your body, via your hands that were small, like your mother’s. Of course — it could never be otherwise — you are everywhere in your stories. Your life was your own, but your writing is ours. By reading you, we know you.

I am thinking about your body and thinking that you were a great sensualist. Food you loved, and champagne you loved, and nature you loved, flowers and gardens and scents, and love you loved. “I have lived very freely,” you told an interviewer asking you about your romantic involvements. Good for you. What’s good for the body is good for the soul.

“This is my body,” said Jesus, and so transubstantiation was born. Those words weren’t spoken last night at St. James’ Anglican during compline; it wasn’t a mass, no communion was taken. It was a very beautiful service, it truly was. Father Kevin was a wonder, all the performers outdid themselves. Listen. You’ll see, and hear, it’s true.

I half wonder if you were there, MG. I suspect you might have been: I’ve been feeling more than a bit haunted by you, these last few months. I wonder if you might have been behind what I think was the highlight of the evening — and there were more than a few. The church is in the downtown east-side of the city: a vibrant neighbourhood, but troubled. Poverty, drug deaths, homelessness. Time was made during the service for a moment of silence. It followed a performance by Veda Hille and Gabrielle Rose of a song Veda set to a text I pulled together by “sampling” questions you, MG, had asked in your stories. It’s amazing. It just is. During this time when the congregation — I think about 60 people came — had the chance to think their thoughts, a fellow came in from the street. He had, safe to say, no idea why we were there, why we were being quiet. He walked slowly, deliberately up the centre aisle to the lectern, and the flowers — sunflowers and gladioli — and the photo of you. It looked like a funeral, really, and I guess he thought that’s what it was. He looked tenderly at your picture, crossed himself, turned around, walked out. The silence ended with a recording of your voice — you’ll hear all this if you listen to the recording — and as you were talking, an ambulance drove by, siren screaming, drowning out your words. They’re audible on the recording because, well, it’s a recording. Then the silence returned, and there came the sound of raucous gulls. It’s hard to describe, you had to be there, but I felt like you were with us in the room, that you were laughing, maybe, and that you were doing what you did best, which was to bring the world in, all its loveliness and all its emergency.

I’m tired, MG. I’m going to stop now. This has been fun. It’s time to wrap it up. I really, really need to sleep. Thank you for what you said and how you said it. Thanks to everyone who’s spent some time here, and everyone who’s taken the time to talk. I won’t name names. Thanks to everyone who took part in the compline service, performing or preaching or participating. Today is Veda’s birthday and it’s mine: 67. Everyone born on this day, or on either side, thinks the Perseid meteor shower is a show that was made with us in mind. I bet MG thought so, too. But the thing about the Perseid is that it’s expected, it’s predictable, it’s known. It’s remarkable, yes, or can be; but it’s regular as clockwork. It’s not a surprise. I don’t think of MG as part of that traveling astral circus making its yearly stop. I think of her as a bright light that appears when you least expect it, when it’s the last thing you’re thinking about or looking for, that comes out of nowhere, entering the atmosphere, gorgeous in its extravagance, fleeting but unforgettable, it’s all fire and colour, the oxygen corrosive, it give you its gift as it burns out its body. Thanks for reading, xo, B

Photos by Bill Pechet of Veda Hille, Gabrielle Rose, Shefa Siegel, and the visitor. Photo of Mavis Gallant by Nance Baele. Used without permission. I don’t think Nancy will mind.