Me again. This always happens: months of slovenly inactivity, a sullen silence, then an intemperate spate of logorrhea. I promise this won’t go on. I take the time to trouble you with this now only because the date - June 7 - is germane. I’ll get to that to that central point soon, and will try to keep it short on either side.

I told you about my daffy undertaking, a collective biography of all the Elizabeth Taylors who weren’t Elizabeth Taylor. Many of these ladies were long-lived, none more so than Elizabeth Taylor who was said to be 131 when she died “at her lodgings in Piccadilly,” in April of 1764. Also notable was Elizabeth Taylor of Indiana for whom the worst was predicted when she was struck by a bus, age 90, but who rallied, endured, and went on to get her name in the paper in 1905 when she made a quilt for President Roosevelt, and then a few years later when she ran a footrace with the matron of the home for the indigent where she lived, and then again when she posed for a portrait while smoking her pipe at the age of 100, and then again when she died, in 1913, age 101.

Elizabeth Ricketts Taylor, b. 1888 - I mentioned her in my last writing - also made it to 101 before she shuffled off in 1989. Her 1909 marriage to Albert lasted about twenty years; after their divorce, she stayed single. She lived with her mother, Nettie, and found community among the versifiers of Portland, Oregon, alongside whom she published poems in the local papers. She often dealt with disappointment in love, but quite wistfully, in a sort of Phyllis McGinley, self-mocking way. She also wrote a great many letters to the editor, some of which were intended to encourage public response, perhaps as an antidote to loneliness. “Don’t we all just love Pat Nixon,” she wrote once, “and the way she has restored common sense decency to our hemlines?” Or, “Aren’t we all just so upset by the way the Reds have taken over Reed College?” Or, “Am I the only one who objects to smoking on public transportation?” (I paraphrase here, but these are close approximations of her writing.) Sometimes, the bait was taken, either by the like- or contrary-minded, and Elizabeth Ricketts Taylor - she occasionally used a pseudonym, Lucile Beckons - had the satisfaction of engagement, if not unwavering approbation. When she needed to bolster a point historically, she would sometimes refer to her scrapbooks. Given that her self-published selection of poetry, from 1975, The Long Beach, is impossible to find, I rather doubt anyone thought to preserve her collection of culled and pasted clippings. This is a pity. I would love to see them.

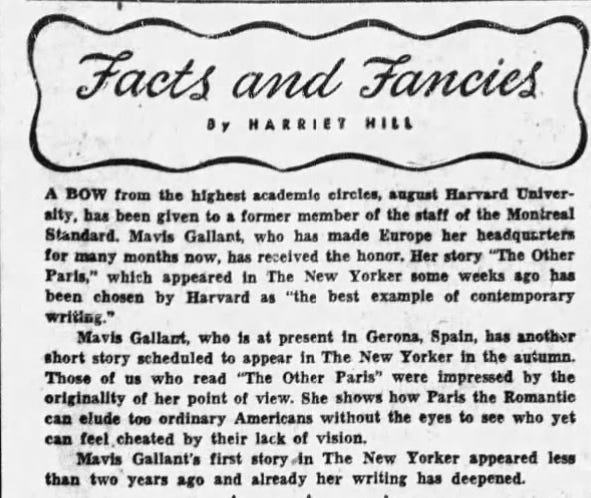

I wonder what Mavis Gallant (MG) did with the cuttings that must have come in the mail from friends who scissored out her name from the Montreal Gazette (rarely the Star) when her various comings and goings and triumphs were reported. This is from July 6, 1953.

Does anyone have any background on this? (He asked, coyly, with a kind of Elizabeth Ricketts Taylor semi-pout.) I’ve poked around, but can find no other reference to any bestowing of ivy league laurels. “The Other Paris” is masterful, for sure, and it would become the title story of MG’s first collection in 1956. But did it cause such a stir that within a few weeks of its publication a special session of the Senate was convoked at Harvard, or maybe just of the English department, for the specific purpose of naming it “the best example of contemporary writing?” Whatever! Anyone receiving such news could only have felt affirmed.

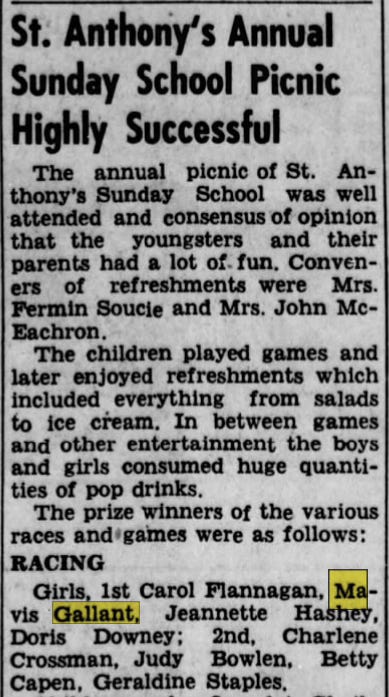

If MG did keep a scrapbook this admiring squib from Harriet Hill (1) would surely have been mucilaged up and placed alongside the other clippings that had tracked her progress publishing in The New Yorker, or that chronicled her holidays in Sicily, in Yugoslavia, in Spain; that noted her presence in Austria, and that predicted she would soon be taking a husband. Did Harriet Hill, who was born in New Brunswick, excise from the pages of the Fredericton Daily Gleaner (July 13, 1954) this mention of Mavis Gallant?

It would have pleased MG, who was partial to the Maritime provinces and to Maritimers, and who was proud to be Acadian-by-marriage to Johnnie Gallant from PEI, via Winnipeg, that she had a fleet-footed Atalanta-by-the-Atlantic as a namesake. Thousands and thousands of Elizabeth Taylors jostled the pages of the papers, vying for attention, but Mavis Gallants were few and far between.

This reporting of the St. Anthony’s Annual Sunday School picnic is disappointing in its lack of specificity. Perhaps by this time, editors weren’t as rigorous as once they had been in ensuring that every single participant in a church or company or union picnic race be named in order of winning rank, along with whatever the race in which they had distinguished themselves: fifty yard dash, sack race, barrel race, three-legged race, etc.

(I know a little bit about this because I recently sacrificed many irretrievable hours to gathering the names of those who had come out on top in the “Fat Women’s Race,” which was a staple of church picnic groupings all across North America for about fifty years from the end of the nineteenth century and well into the twentieth; it seems not to have survived the Second World War. There were often discussion of what constituted “fat,” was it 160 pounds and over or 200 pounds and over, and sometimes quarrels broke out among women who felt that too much leeway was given to the lightweights among their coevals; that someone as slight as 155 pounds would be admitted to the competition, perhaps to spice up the competition. It could get quite fraught. I feel there’s a dissertation there, but for someone other than myself.)

What race did 12-year old Mavis Gallant win at the St. Anthony’s picnic in 1954? It’s a pity we’re not told. I’m guessing she is the same Mavis Gallant who was born to George and Mary in Fredericton on May 24, 1942 (which would then have been Victoria Day, a date mentioned in MG’s short story “The Four Seasons,” as I recall) and who died in St. Thomas, Ontario, February 24, 2000. RIP.

Mavis’s married name was Lynch, and herein lies an irony, in that she came to my attention via a picnic. Bear with me.

There are many contemporary examples of how, concealed beneath and between the stacked mattresses of the mother tongue, are cruelly bruising peas. A welt-raiser of recent vintage is “picnic.” Somehow, the self-deputized beat cops of language and those who resist their authority have found themselves at loggerheads over this usual and seemingly innocuous word. Those who tolerate picnic and its casual deployment in quotidian conversation say it’s nothing more than a commonplace descriptor of an al fresco meal. They say, as well, that the stones that mark picnic’s passage through the dark and pathless forest of etymology (2) are luminous and easy to follow. It’s from the French, pique-nique, and it’s been around, and adapting itself to English usage, for over three centuries.

Anyone who looks even briefly into the history of picnics will quickly learn they were often far from peaceable gatherings. The hamper-humpers tended to be members of special interest groups, church or labour affiliated. Very often, there were rival organizations who were glad of a chance to disrupt the merriment of their ideological opposites. Baseball was a frequent feature of the fun, and there were bats lying about which could be turned to caveman purpose. Often, too, there was booze, a reliable accelerant. Believe me when I tell you there are hundreds and hundreds of stories of picnics gone awry. Here’s but one example, from Oklahoma, but reported in The Buffalo Commercial, July 31, 1897. (3)

Now, this is a fair representation of the kind of crazy mayhem that once disrupted picnics but not necessarily of the linkage to lynching that has latterly riled people who are concerned with decolonizing language. Lynching was not racially specific - whether Ben Vaughn was Black or white I have no idea; there was a Vaughn family at that time in Oklahoma who were prominent members of Chickasaw Nation - but, fair to say, it pertained more to Black people than to white. The history, as no one needs to hear from me, is grim and hurtful, and those who have documented it have noted that some picnics, when they took a violent turn, became lynching parties. Thus, the point has been made that “picnic” and “lynching” are essentially synonymous, and that to say “picnic” is triggering. Claims have also been made that the origin of the word is “pick a n—,” which certainly supports the case for its suppression but is also, well, incorrect, see above re: pique-nique. (Note: this is not to say that “picnic” wasn’t contorted to that purpose. It could easily, in context, have been uglified in just that way.)

Our Mavis Gallant connects to picnics in several ways. (Have I written about this before? Probably!) Picnics come into play, to greater or lesser effect, in, to name but a few stories, “The Four Seasons,” “Irina,” “Potter,” “The Pegnitz Junction,” “A State of Affairs,” and, most memorably and horribly, in “In the Tunnel,” from 1971. A young Canadian student, Sarah Holmes, sets up housekeeping with an older English man, Roy Cooper, a retired colonial prison inspector. They live in the sordid guest house (the titular Tunnel) of an older English couple, the Reeves, a seedy, unappealing pair. The Reeves’s niece, Lisbet, comes to stay, and things begin to fall apart between Sarah, a genial flake, and Roy, a dyed-in-the-wool cad. At Sarah’s instigation, even though she’s been hobbled with a badly twisted ankle, the threesome goes for a picnic, nearby Nice, at a church Sarah admires for its grotesque frescoes of the Last Judgment, the suicide Judas Iscariot with his guts hanging out, surrendering his soul to Satan. (MG was certainly thinking of this image from the Chapelle-Notre-Dame-des-Fontaines, in La Brigue.)

Nothing goes as planned, the picnic is a disaster, callow Roy’s duplicity is reinforced, the relationship ends with a whimper, and Sarah gets out of the Tunnel. It’s a GREAT story; there’s something about its pulse that almost suggests Alice Munro, and I can imagine Alice reading it - she would soon start publishing in The New Yorker - and paying it granular attention.

However, the two picnics with which I’m most concerned, on this June 7, 2025, are from much earlier in MG’s career as a fiction writer. As noted above, her movements after she quit Montreal for Europe were often charted by the Gazette, as here, mid-paragraph, from 1952.

Anyone reading that might be forgiven a pang of jealousy or some similar less-than-charitable twinge. The lucky thing! Having the time of her life in Madrid! A bit hot, yes, a bit noisy, sure, but Madrid! Por favor, toreador! But that, of course, was the time of her life she would fictionalize a few years later in “When We Were Nearly Young,” and about which she wrote so memorably in her journals, excerpts of which, as “The Hunger Diaries” were published sixty years later in The New Yorker.

This extraordinary document - the diary, I mean, and if you haven’t read it, do - covers March - June, 1952. MG describes with a kind of mordant, desperate, hunger-fuelled, delirious glee the near famine conditions under which she existed - pawning her typewriter, her clothes, her clock - in Barcelona, in Madrid, while waiting for the arrival of money from her agent, Jacques Chambrun, whose double-dealing, traitorous ways would have made him a perfect model for disemboweled Judas. As is now well-known, he’d made a practice of embezzling dough from his clients, including Somerset Maugham and Ben Hecht. Finally, via communication with someone at the New Yorker, MG begins to figure out that she’s been on the receiving end of something a long way from honourable, then money arrives at the American Express office, and she buys good white bread.

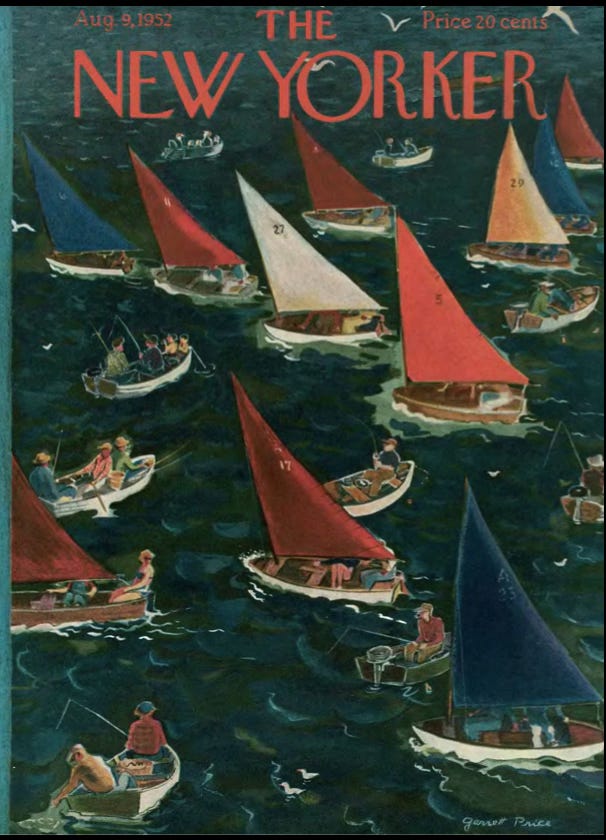

Both of the stories for which MG was expecting payment while living on potatoes and cigarettes were published in the spring / summer of 1952, and both have to do with picnics. It was important for MG, as she often said and as I’ve written before any number of times, that her life be “settled” by the time she was thirty. That was the big gamble of quitting her secure job at the Standard, age twenty-eight. She had two years to prove that she could live by fiction. So, it could only have been gratifying to her to see her story “The Picnic,” the third accepted by the magazine, in the issue dated August 9, 1952: two days before her thirtieth birthday. Deadline met.

Just before Christmas, at the end of 1951, Weekend Magazine, as the Standard became, published MG’s entertaining profile, “The Busy Mrs. Biddle.” Margaret Atkinson Biddle - like that talented St. Anthony’s athlete, Mavis Gallant Lynch, she was from Fredericton - was a Canadian who had married well. Her husband, General Anthony Drexel Biddle, was — I think this is right — the officer in charge of the American occupying forces. Margaret Biddle, as his spouse, and mother of their young children, was, indeed, very busy. The insights MG gathered while looking into the requirements, practical and diplomatic, of a family in such a particular position must have found their way into “The Picnic,” which tells of a bridge-building exercise, a picnic, meant to foster good will between the Allied occupier and the French in the village where they’ve set up shop. It’s sly and wonderfully-wrought, especially memorable for the portrayals of the children and of the elderly French widow, a minor aristocrat, whose home has been commandeered.

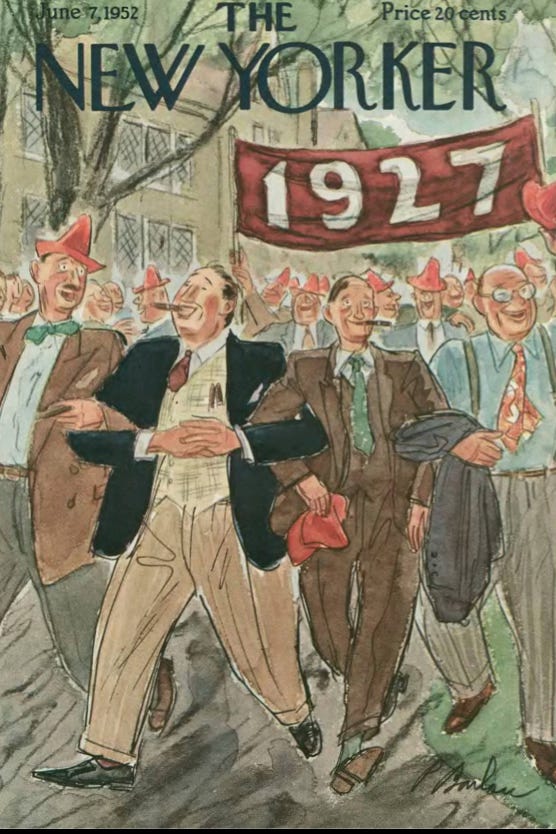

In what the New Yorker eventually published as “The Hunger Diaries,” MG made note of correspondence she’d had about the first of the two stories to appear in the magazine, in the issue of June 7: see cover illustration at the top of this post.

In “One Morning in June,” two young Americans, Barbara and Mike, go on a picnic near Menton, at Cap St. Martin. That story was included in The Other Paris (1956) under the title given it by the magazine. When it appeared again, more than half a century later, in Going Ashore (2009)the original title, “One Morning in May,” was restored. The magazine, without consultation, had made the alteration, presumably to fit the fact of its June publication. May, June? What was the difference? MG’s friend Nancy Baele - whose intelligence in this regard I cite here in the fervent hope she won’t mind - told me that MG told her that she was offended because she had worked hard to get every May-specific detail just right: the slant of light, the botany, etc. In the story, Barbara and Mike, who don’t really know one another, whose date has been engineered by Barbara’s grandmother, who have not much in common apart from being young and American and away from home - that’s actually quite a lot of commonality - have their picnic within sight of a Cap Martin monument.

They ate their lunch in silence, like tired alpinists resting on a ledge. Barbara screwed her eyes tight and tried to read the lettering on the monument; it was too hot to walk across the grass, out of their round island of shade. "It's to some queen," she said at last, and read out: ‘Elizabeth, Impératrice d’Autriche et reine de la Hongrie.’ Well, I never heard of her, did you?

In her journal, in addition to the title issue, MG notes an inaccuracy in the spelling of the inscription: a rare slip-up from the ace team of New Yorker fact checkers. MG must have forgotten about this discrepancy because while the title was corrected for the story’s resurrection in Going Ashore, the quote remains inaccurate. There are, in fact, two errors. The memorialized queen, a Menton regular, was Elisabeth, with an “s,” and, on the inscription, no article precedes Hungary: “et reine de Hongrie,” is how it was chiselled into the marble of the plinth. Marble, or whatever stone! Oh, well. There is a crack in everything, it’s how the light gets in: as some other Montrealer famously said.

June 7, 1952. Seventy-three years ago this very day. MG’s second New Yorker story hits the stands; number two, of ever so many more to come. “One Morning in June,” (May, if you’d rather) is resonant with future echoes. It reminds me of “Wing’s Chips,” in that Mike is a painter much in the same way Stewart Young, MG’s father - plainly, it’s he who’s portrayed as the mural maker - was a painter, talented but amateur: the fate she’d feared for herself, but now knew she would escape. Barbara, entirely aimless, describes at length to Mike her misbegotten audition for a radio play, which reminds me of how Linnet Muir, in “Between Zero and One” (1975) goes to an audition for a CBC Radio Drama producer, named Margaret Urn, and brings along a new Thornton Wilder play, The Skin of our Teeth. It proves too much for Miss Urn to bear, and she asks instead that Linnet read from Dodie Smith’s Dear Octopus. For Linnet, as for Barbara, no part is forthcoming. “One Morning in June,” to use the title of its first publication, also reminds me of “When We Were Nearly Young,” with all its Hunger Diaries harmonies, because it is, essentially, a story about youth, about the romanticizing of youth, and about the ending of youth, and what comes next, and about how ill-prepared everyone is for it. (MG knew well that there was no worse rehearsal for adulthood than being young.

And now, arriving at the peroration, I remember too, as no doubt do you, that it was on a “bright morning in June” that Linnet Muir (this time, in “In Youth Is Pleasure”) arrives back in Montreal from New York, carrying most of her belongings in an Edwardian picnic hamper her father had brought from England; the same hamper that turns up in “Varieties of Exile” as the storage place for Linnet’s manuscripts. (4) Perhaps you have more to say about MG and picnics. Please be in touch! As for me, on an unseasonably cold June day in Manitoba, I’ll leave it her for now, adding only that the poetry group to which Elizabeth Ricketts Taylor belonged in Portland, Oregon, had a picnic every Fourth of July. Never, as near as I can tell, did it devolve into fisticuffs.

Thanks for reading, cheers, BR. And look! Footnotes!

(1) Harriet Hill, 1903 - 1991. She was raised in Yarmouth, and attended the College of Practical Arts and Letters at Boston University. By the time MG began writing for the Montreal Standard in 1944, Harriet Hill was well-established at the Gazette, often reviewing books, often writing about “women’s issues.”I wonder what MG’s connection was to her, and to her Standard colleague Kate Aitken? Did they take her under their wing, advise her? Or would she have resisted such ministrations? Harriet was in her 60’s when she married longtime bachelor Wilfrid Watson Werry, a playwright and photographer - apparently, a friend of Robert Frost - who died in Las Palmas in 1971. (As a schoolboy, he won the Gymnastic Challenge Cup four years running - 1912 - 1915 - the first ever to do so.) When Harriet died, in Ottawa, her brief obituary in the Gazette made no mention of her long career at the paper, nor was her passing otherwise remarked. Bastards.

(2) Oh, Bill. EXCELLENT writing!

(3) Ben Vaughn - I know you want to know - was not strung up, but was sentenced to eighteen months in the federal pen. He applied for a pardon which was granted, but not until twelve hours before he’s served his full term. What became of him after his release, I can’t say.

(4) Likewise, in her Margaret Laurence memorial lecture, 1988, MG remembers starting her job at the Montreal Standard on a “bright June morning.”

Golly. Judith, thanks. What an amazing response. I'm just goofin' around, all I've ever done! What a good writer you are. I didn't know you were on Substack - I don't pay enough attention, obviously. Will have a read. Many thanks again.

I don’t know whether to applaud or send help. This felt like stepping into a very elegant whirlwind — footnotes flying, forgotten Taylors elbowing for space, Mavis Gallant gliding past on a picnic blanket muttering about the New Yorker. I got gloriously lost (several times), but your affection for the nearly-forgotten is so clear it made me teary — and then, just as quickly, made me laugh out loud. As a fat woman who would absolutely have taken gold in the sack race (and possibly lit a cigarette at the finish line), I feel seen. You always did know how to spin a tale. Now I need tea, a quiet room, and possibly a fainting couch.