Grief, Memory, Three O'Clock in the Morning: June 11, 2025

RIP Edmund White, Friend Of Mavis; Happy Birthday, Allan Gurganus, MG New Yorker Bunkmate, Kinda Sorta

More and more I become aware of the chilling shadow, the fetid breath, the unwelcome presence of something I can only call cognitive decline. CD. Relentless stalker, determined dogger of my heels, which are sensible heels, engineered with the elderly in mind, to reduce the risk of falling. Our hips, darling; we need to be mindful of our hips. Every day another word or phrase fails to traverse whatever synapse needs breaching in order that image and word be reunited, their tender embrace thwarted by the fearsome troll who guards the bridge. Just now it was “chafing dish.” Yesterday, it was “hologram.” The day before, “Pringles.” Don’t ask. I’d gladly disclose all the recent rest but, well, you know - I forget. Every morning I text myself my social insurance and personal ID numbers — SIN and PIN, what fun to write! - just to reassure myself I still remember them, and also to have a recent record at the ready, should they be required at a moment they’re refusing to come when called. Bad doggies. Bad. Bad.

Dementia. Here it comes, zombie-gaited, staggering down the street under the hot noon sun, foaming at the mouth. Everyone scatters, shrieks, but cries for help go unanswered. There’s no Atticus Finch to bravely put down his book, dust off his bifocals, shoulder his rifle, and take the thing down. Hiding is hopeless, the beast can sniff you out, it has x-ray eyes that will penetrate the snazziest safe room. Run? Sure, you can try to run, but what? In THESE heels? You might as well just abandon all hope, smear yourself with liver paste, lie down on the sidewalk and embrace your fate. Surrender Dorothy.

Edmund White died last week, on June 3. He was 85. After his first novel in 1973 - irony alert, it was Forgetting Elena - he published thirty-four more books, memoirs, biography, fiction, not to forget (as if) his co-authoring of The Joy of Gay Sex. There is, apparently, a new novel, historical, about the gay brother of one of the numbered Louis, Louis XVI probably - mais excusez-moi, j’ai oublié, qu’ils mangent de la brioche etc. - all typed up and ready to go. Mr. White lived long enough to see published - just a few months ago - his (presumably) penultimate tome, The Loves of My Life: A Sex Memoir. I gather it’s a kind of paean to the 3,000 or so men with whom he enjoyed congress during those rare moments when he wasn’t at this desk, processing words. Stay for a cigarette? I’d love to, but I have to hurry home and write it all down. Well. Every boy needs a hobby. 3,000! A triumph of both the libido and the archival instinct. It rather reminds one of Dorothy Parker saying, “If all the debutantes were laid end to end, I wouldn’t be surprised.” (1)

All those gentlemen callers! Edmund White, plainly, finished up his time on earth with his memory in tact, God bless him. He lived in Paris, on and off, for many years, and once, on one of my rare visits there, late on a summer day, in the crepuscular shade of the Ile de la Cité, or the Ile St. Louis, or one of those impossibly tony precincts, I saw someone I took to be him (it might have been anyone, but there was an Edmund White cast to his features), and he was lounging about in that faux- flaneur attentive way that suggested availability. I considered undertaking some provocative flouncing, but didn’t, and I’m sorry now for the wasted opportunity - not that I suppose he would necessarily have risen to my bait - because I might have been among the 3,000, which wouldn’t have had about it a Mayflower cachet, but it would have been nice to have been remembered in his late life catalogue. (And how dire to have been forgotten!)

I sound impertinent because I am impertinent, and I shouldn’t be. Edmund White - the much decorated winner of many awards, including the Pulitzer Prize - was plainly a man of huge energy, endowed with great talent, and someone whose gifts were perfectly tailored for the time in which he deployed them. He had the good fortune to come along at the right time, and those times were lucky in his arrival. His coming of age dovetailed with the age of gay liberation, and he gave that movement voice and, to a considerable extent, shape. He was graphic in his sharing, explicit, described human experience, varieties of love, that hadn’t found a place in mainstream fiction. He crafted books that needed to be written and that would have been impossible to writers of similar temperament of an earlier generation.

But Bill, you might well inquire, why are you writing about Edmund White here, on these “pages” where your stated purpose is the veneration of Mavis Gallant (MG)? It’s just because on the news of his death it was to MG that my mind made the (by now slow and reliably unreliable) leap. I thought of how - I’m sure I’ve told you this before - her name comes up in his 2014 Paris memoir, Inside a Pearl. (2) I’m working here from memory - so, measure out those grains of salt - but he speaks of MG as one of the few non-French writers to take on the French on their own terms, and tells of being at lunch with her at Le Dome or in one of the landmark restaurants. She was, he said, by then “bent over like a hairpin” with arthritis, but ceding nothing, game to engage. Even in some quite early photos, from the late 50’s, you can already see the arthritis in the joints of her fingers. I’ve thought often - and yes, I know, written before - about how much pain she must have had to endure, and how remarkable it was that she wrote as much as she did.

My memory is now so riddled that I can’t remember when I interviewed Edmund White, nor why, nor where. I know I did, and I think it must have been for the Vancouver Writers’ Festival, but all the details are lost to me. It was a public conversation, not in a radio studio, and I have an opaque recollection of a moment when he paused and gave me a long look that suggested his patience was tested, but that happened often in my interviewing career; it was work for which I was never intended, I can’t understand how I got away with it as long as I did.

Worse still is that I can’t remember when or whether I interviewed Allan Gurganus. This is appalling to admit, shameful, but it’s true. I hear a faint bat-like beeping, an echo locator of such a conversation; see faint traces of words we might have spoken stick-written in sand over which too many tides have washed to allow for certainty. I’m not sure if what I remember was an actual event, or if I merely wished for it after reading his short story collection White People, which I loved in that moment. Or was I possibly the producer of a radio interview between Vicki Gabereau and Mr. G? That, too, is possible; it was in just this regard that I met MG for the first and only time. My consolation is that this dithering over when and whether is of no concern to Allan Gurganus, nor would it have been to Edmund White, whose lips were not forming my name as the darkness deepened.

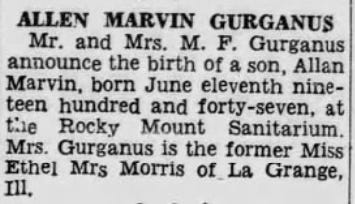

Allan Gurganus - if you persist in reading you’ll find out how this is germane - is on my mind because I’ve kept on my shelf for thirty-six years a copy of his great big bestseller, Oldest Living Confederate Widow Tells All, purchased the year it was published, 1989; the year he turned 42. Today, June 11, is his 78th birthday. I didn’t know that - the business about his birthday, I mean - when a few days back I took from said shelf, obedient to I know not what impulse, the novel and started to read it, at long, long last. I’m so glad I did. I can’t think of the last time I’ve felt such deep, immersive pleasure in reading. The book - the channeling of that voice, the invocation of that spirit, and the evocation of that place - is a miracle. The fuss of almost forty years ago was merited! Does this relate to MG? Well. It does and it doesn’t.

When last I wrote here, it had to do with picnics; with how they figure in “One Morning in May,” and “The Picnic,” MG’s second and third published New Yorker stories. (The first of these appeared as “One Morning in June,” an editorial change made without consultation; the title was corrected / restored in later anthologies.) I was interested to note that in that New Yorker of June 7, 1952, “One Morning in June,” kept company with a piece of short fiction by James Thurber who was, in ways I’ve never understood, an MG family friend, or, at least, acquaintance. (I wonder if the Thurbers might have been Connecticut neighbour of the Quackenbos family with whom MG lived for a while.) Did Thurber, in those early days of MG’s history as a New Yorker contributor, put in a good word? Whether he did or whether he didn’t has no bearing on the quality of her work, which stands on its own. But a leg up is a leg up, after all, especially when it comes from such an established insider, and Allan Gurganus got just such a boost from John Cheever when Cheever, who was Gurganus’s teacher at the Iowa Writers’ Workshop, sent his student’s story, “Minor Heroism,” to the magazine and it was published in the issue of November 18, 1974.

By a strange coincidence - hackneyed phrase, but accurate here - my copy of Confederate Widow was placed next to the selections from Cheever’s journals that came out in 1991. They are as magnificent as they are sad, and a bit maddening in that they are organized chronologically, but not specifically dated; nor are places named, although that can usually be contextually divined. We can assume, I think, that it was in Iowa, and about Allan Gurganus that Cheever wrote here, in 1973 or 74:

A. comes, and I like him very much. I find him uncommonly sympathetic, and wonder if this is some form of narcissism: do I invent this sameness in our thinking? But this could be an invention of mirrors. At lunch we talk about debutante parties, which is a wrong turn to take, but later he tells me that after leaving me he had a nightmare about his father; that my claim to our equality is unacceptable to him. In a spasm of paranoia I think he is referring to his youth, his intelligence, his freshness of mind, but it seems that he would like to have me as an object of veneration. I believe him to be telling the truth; I cannot imagine him not being truthful. Or anything else unpleasant. We walk up the river in the sun. He is wearing sailor pants and is inclined to swing his hips, and I think people look at us as if we had been scoring, which is untrue. They are closing up the Ferris wheel and the carrousel for winter. Some camera students are photographing this autumnal commonplace. The chairs and tables are stacked on the terrace where refreshments are served. Trucks are taking the benches out of the pavilions. All that is left in the zoo is two bison and two burros. I see very little beyond the fact that I am easy in A.’s company and that the architecture on the west bank of the river is, without exception, ugly. We part the student and the teacher.

“Minor Heroism” is a terrific story and, no doubt, highly autobiographical. Gurganus’s gifts as a painter became apparent in childhood. In his mid-teens, in his home of Rocky Mount, North Carolina, he had solo shows, and he continued to paint and exhibit well after he was established as a writer. “Minor Heroism,” is told in three short chapters. The exterior sections are in the voice of a man who remembers his difficult, at times violent relationship, with his father, a war hero, a bombardier who took part in the firebombing of Dresden. (There’s an extended passage that elides images of cities burning with china breaking, soup tureens exploding, that any writer of any age would swallow carpet tacks, or carpet bombs, to have produced.) The middle chapter is in the father’s voice. He wonders how it is that he came to have such a son, with such, well, bohemian proclivities.

“Minor Heroism” is often cited as the first story with a specifically gay character to appear in the New Yorker, and there is no doubt the young artist’s sexuality is the cause of the father / son schism. However, unlike Edmund White, whose gift was for candour and who didn’t stay his hand when it came to calling a blow job a blow job, Gurganus’s writing, while it leaves no doubt as to its intention, is never on this count explicit. Exactly the same thing can be said about MG’s “Travellers Must Be Content,” which appeared July 11, 1959: her story of Wishart, who masks his sexuality with dissembling and exploits lonely women who want to enjoy male companionship without the complication or threat of sexual involvement. (She painted an even plainer, and funnier, and in some ways more worldly-wise portrait of a “gay deceiver” in 1953 in “The Deceptions of Marie-Blanche,” which was published in Charm. I would be very surprised - and I have no basis other than inkling for saying this - if MG, during her time as a journalist at the Standard, wasn’t tempted by the possibility of writing about Montreal’s gay demimonde; I suspect that’s just what she was doing, in a coded way, when she wrote her feature about bachelorhood.)

There are top drawer interviews with Allan Gurganus, an extraordinary chronicler of both the Civil War and of the AIDS crisis - decimators that unite two different generations, each with a similar body count of young and beautiful men - in the New Yorker, in the Paris Review, and all over YouTube (3) Watching one video of recent vintage it was impossible not to notice the evidence of dyskinesia, which would make the work of writing or painting even more challenging than is inherently the case, and it made me think of MG, the arthritis, the trial it must have been. His spirits, though, seem undiminished, his old soul brightly burnished.

Basta. I’ve tested your patience enough, and I want to get back to the miraculous Lucy Marsden, the Confederate widow telling all. Rarely have I been so glad a novel is so long. RIP, Edmund White. Happy Birthday, Allan Gurganus. Many more. Now, I’ll hit “Publish,” and send this out into the world, replete, as always with uncaught errors and offending infelicities. Oh, well! Within an hour, I’ll have forgotten all about it.

Thinking of this account of multiple sexual conquest I also remembered Yeats, and his poem “The Death of Cuchulain,” the way it memorializes the lusty Queen Maeve. Why I still remember this from my Anglo Irish literature class, 1975, I can’t say.

The harlot sang to the beggar-man.

I meet them face to face,

Conall, Cuchulain, Usna's boys,

All that most ancient race;

Maeve had three in an hour, they say.

I adore those clever eyes,

Those muscular bodies, but can get

No grip upon their thighs.

MG and Edmund White had a friend in common in Marie-Claude de Brunhoff, who’s a central character in Inside a Pearl. In MG’s late-life interview with Christine Evain and Christine Bertail, speaking of fitting into French society, she remembered how, “I got very cross at a French dinner party one night because it was the at the beginning of the ‘90s and it looked as if Quebec was going to secede and I said, ‘Je trouve ça inouï que personne ne m’ait posé une seule question. Je suis quand même née au Quebec! Je suis proche des francophones!” Et Marie-Claude de Brunhoff m’a répondu, “Mais Mavis, je pense à vous comme une Française!’ et c’était sincère! Mais je n’étais pas contente. And they were all trying to make up for this: ‘Alors expliquez-nous ce qui se passé.’ ‘Non! C’est fini! J’ai fermé le chapitre!’”

Totally normal to forget words now and then. At least, that's what I keep telling myself.

Always happy when you turn up in my inbox.

Great writing... love this one. Proving you can move beyond MG now... altho' it's funny how you you still came around the circle to her again. You're excused! lol Thank you for the book recommend. I checked at VPL and they still have a copy of Gurganus' novel - can't wait to check it out!